A-CAPP Center Report

How potential changes could create too many loopholes for it to be useful or effective

Kari Kammel1, 2022

Working paper: last updated February 11, 2022

Executive Summary

Recent proposed amendments to the federal and state level versions of the INFORM Consumers Act would create confusing provisions, ambiguity, and loopholes that could effectively render the bills useless and in the end would not provide protections for consumers shopping online.

- Online marketplaces definition should remain as proposed:

- Including all of the proposed actions–“sell, purchase, pay, store, ship, or deliver”

- No exception is needed for certain types of online marketplace or intermediaries, since to quality they need to meet all three criteria: (A) allowing, facilitating or enabling third party sellers to sell, etc. consumer products in the US, (B) used by the third party sellers for that purchase, AND (C) has a contracted relationship with consumers governing use of platform to purchase consumer goods

- Should remain as types of action instead of a type of industry, i.e. curated v. non-curated online marketplace

- Proactive Efforts Should be Applauded and Required, but not grounds to exclude an online marketplace from qualifying under this bill

- Potential “Second Notice” would render timeline confusing, unusable and could lead to no effective suspensions of counterfeit sellers

- Replacing a concrete time in the timeline with “reasonable time frame” would also render timeline indefinite, potentially creating an environment for no suspension of counterfeit sellers

- Allowing online marketplaces to block “direct, unhindered communication” from the consumer after their purchase to the seller for reasons of “fraud, abuse and scam” might essentially chill the ability for consumers to contact the seller and will be impractical in implementation

- Requiring marketplaces to permanently delete or dispose of this information within 24 months of receipt and not share or disseminate the information to any party without a law enforcement subpoena would hinder proactive collaborations with law enforcement and make it exceedingly hard for consumers to get this information for a lawsuit

- Striking the required bank account information and substitute good supplier information would eliminate two known techniques that are used to help prevent illicit goods from being sold to consumers

The goal of this bill is to protect consumers proactively from the potential harm caused by the sale of counterfeit and/or stolen goods by third party sellers in online marketplace and these amendments would chip away at that much needed protection.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

WHY IS INFORM CONSUMERS NECESSARY?

DEFINITION OF ONLINE MARKETPLACE

STRIKING BANK ACCOUNT INFORMATION OR SUPPLIER INFORMATION

PROACTIVE EFFORTS: REQUIRED OR EXCLUSION?

TIME FOR NOTICE AND POTENTIAL SECOND NOTICE

REASONABLENESS V. CONCRETE TIMEFRAME

FRAUD, ABUSE, SCAM AS AN EXCEPTION TO DIRECT, UNHINDERED COMMUNICATION?

DESTRUCTION OF INFORMATION AFTER 24 MONTHS AND SUBPOENA

INTRODUCTION

The House Rules Committee recently reported the America Creating Opportunities for Manufacturing, Pre-Eminence in Technology, and Economic Strength Act of 2022 (America COMPETES Act)[1], which includes INFORM Consumers Act that was initially introduced into Congress in 2020.[2] While a comprehensive multi-faceted approach to combat trademark counterfeiting is vital,[3] one of the most important tools in this approach is an applicable, balanced legal structure for intellectual property owners to be able to protect their trademarks in order to ultimately protect consumers.[4] The inclusion of this bill as a cause of action for unfair or deceptive acts under the Federal Trade Commission Act and enforced by the FTC will help to protect consumers from purchasing potentially dangerous counterfeit and/or stolen products being sold by third party sellers online.[5]

WHY IS INFORM CONSUMERS NECESSARY?

The existing legal frameworks did not anticipate e-commerce and we find ourselves in a place where they do not really address the phenomenon of third-party sellers of counterfeit, or stolen, products online in a global marketplace, a concept that I earlier applied the label “law disruptive technology.”[6] Importantly, as we examine the INFORM Consumers and potential changes, we should consider how these technologies might shift and evolve in the next few years to ensure that if this Act becomes law it will still have an impact five years, ten years, and twenty years from now. Currently, consumers are essentially unprotected when they buy a non-legitimate good online from a third-party seller, as it is not a requirement for online marketplaces to vet sellers or their goods under the law.

As INFORM Consumers has been combined into America COMPETES ACT and state legislatures are simultaneously putting forth their state versions of the INFORM Consumers Act, proposed amendments that narrow the language even further will detract from the balance INFORM Consumers creates, rendering it ineffective or contradictory, which will allow for the continued sale of counterfeits by third party sellers online unhampered.

Definition of Online Marketplace

The definition of “online marketplace” in America COMPETES Act (the INFORM Consumers part located in Section 20213)[7] and many of the state proposed bills patterned after INFORM Consumers is specific, but broad because it seeks to cover those who facilitate the e-supply chain that starts at the posting of a counterfeit product up through the purchase and through to the delivery of a product.[8] Although several types of online companies have proposed amendments to this definition to try to be excluded from qualifying as an “online marketplace,” its focus on the activity and not the type or industry categorization of the company is important for several reasons.

Inclusivity of Various Actions in the Online Purchasing Process

As many who has worked in brand protection or anti-counterfeiting efforts can attest, preventing counterfeit goods from entering a supply chain or reaching a consumer takes collaborative effort from everyone in the supply chain including up to the retailers who sell to consumers.[9] In the online space, the end of the supply chain looks very different moving from third party sellers to the consumers, particularly with online marketplaces who are allowing third party-sellers to sell product and do some combination of enabling them to sell, purchase, pay, store, ship, or deliver.[10] If these activities are removed and limited to the “sale” or “direct sale” of goods, we will be eliminating the capacity for other actors in the supply chain to appropriately vet and monitor those third party sellers using their services. Limiting to “direct” sale narrows the definition too much and would create problems that might exclude existing online marketplaces and not recognize the way the online supply chain operates and would also endanger consumer purchasers I believe all of these actions are important to keep in this provision.

Online Marketplace Must Meet All Three Criterion to Qualify as Such

The definition found in (f)(4) notes the following requirement:

- Includes features that allow for, facilitate, or enable third party sellers to engage in the sale, purchase, payment, storage, shipping, or delivery of a consumer product in the United States;

- Is used by one or more third party sellers for such purposes; and

- Has a contracted or similar relationship with consumers governing their use of the platform to purchase consumers products.[11]

Some companies that generally engage in the activities notes in section (A) have raised concerns that this bill will loop them into having to comply with this bill. However, this only applies to entities (or individuals) who are engaging in all three of these activities, most importantly section C, which is using of a platform to purchase consumers goods.[12] A basic reading of this would exclude companies who are involved in shipping or delivery or even sales or storage of products, unless they are actively engaging in the activities of Section B AND C as well.

Actions Over Business Types or Industry Categorization

The definition of online marketplace defines the actions that will qualify a company or individual for having to comply with this provision. This will allow for future flexibility with how various online companies could be included or excluded depending on their activities and businesses with which they choose to be involved. If certain types of businesses are excluded or given safe harbors (such as curated or non-curated marketplaces), this could be problematic upon immediate implementation of the law, but also as businesses continue to develop and change, excluding some that may decide to branch into this kind of effort. Curated marketplaces instead seem to have a leg up in compliance with this law as they already have proactive vetting efforts in place.

STRIKING BANK ACCOUNT INFORMATION OR SUPPLIER INFORMATION

Additional potential amendments include striking the bank account information under (1)Collection[13] and striking supplier information.[14] The existing information on the bank account information is vital, as has been shown by an action, both civil and criminal that has sought sellers of counterfeit or even stolen goods in a “follow the money approach.”[15] By removing this provision, this would take the teeth out of the bill, which targets the one thing that counterfeiters and those selling stolen goods are looking for—profit.

If the provision regarding notifying if a third party seller used a different seller to supply a consumer a product and then to authenticate it is stricken, its removal will make the bill wholly ineffective against those sellers who are peddling counterfeit and stolen goods. All they would have to do to sidestep it is to sell and authenticate one genuine product and the rest they could use the ‘bait and switch’ to sell illicit goods. Again, this would put consumers back into the place of not knowing the origin of their goods since there would no longer be a requirement for ‘substitute goods.’

PROACTIVE EFFORTS: REQUIRED OR EXCLUSION?

In the online space, some online marketplaces (assuming the broad definition in the bill) take proactive[16] efforts to vet those third-party sellers and some do not. Many also offer some combined version of proactive and reactive[17] anti-counterfeiting efforts. However, both are necessary. In the past few years with the talk of possible legislation and increased number of third-party counterfeiters online, some online marketplaces have begun to offer more proactive vetting activities. Some argue that INFORM is not necessary or their platform should be excluded because of these proactive efforts. While these are very positive steps taken by these companies, the efforts still lack transparency both for consumers and brands, and unfortunately, counterfeits remain rampant in the online space—thus a uniform requirement would help regulate this space that is becoming more dangerous.

TIME FOR NOTICE AND POTENTIAL SECOND NOTICE

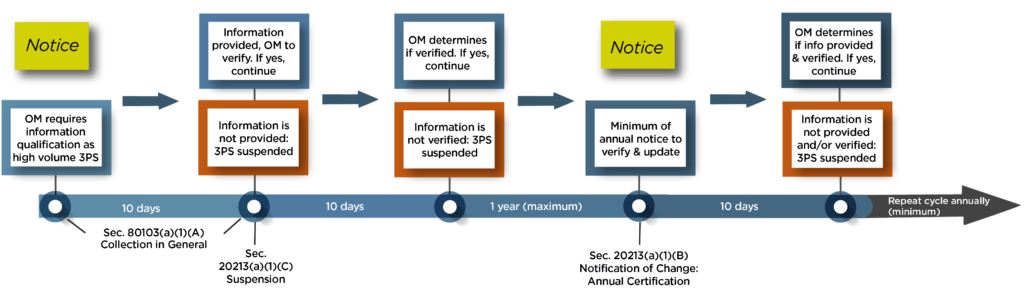

Currently, with the House version of INFORM Consumers noting every requirement was 10 days after the triggering action would lead to the following timeline.

Figure 1. Current Timeline with Notice. Diagram showing timeline of INFORM Consumers timeline with 10 day triggering action and one notice

The current reporting and notice process gives twenty days from the point of qualification for the initial determination that a high-volume third-party seller to provide the required information and for the online marketplace (denoted “OM” in the graphic) to verify it, otherwise there is suspension.

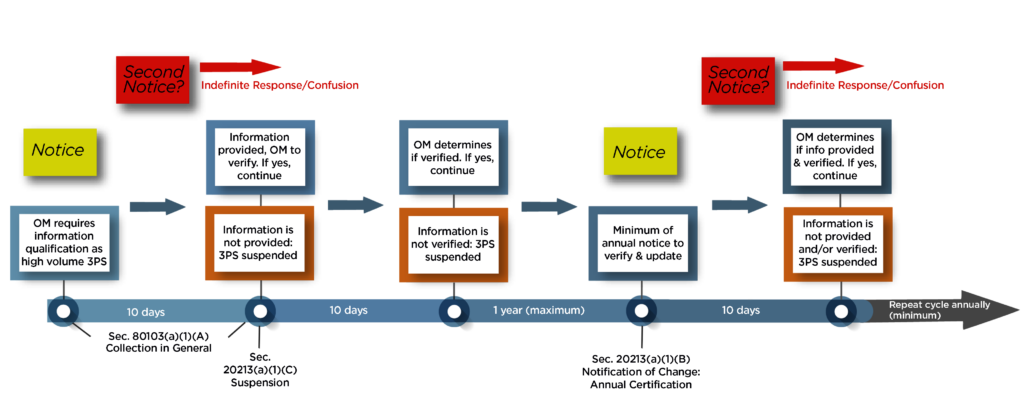

Figure 2. Second Notice Confusion Timeline- Diagram showing timeline of INFORM Consumers timeline with the potential amendment of “Second Notice” causing confusion

Proposed amendments to some of the state bills, such as the above state version of INFORM Consumers bill mention a second notice without clarification as to the timing and how this extension would impact the rest of the timeline.[18] In no other place in the bill does it define the second notice, note when and why a second notice is necessary. Further, it does not incorporate it into the timeline at all, with no period (10 days or other) triggering the sending of a second notice, or how many days a third-party seller has after a second notice. This could lead to the loophole that an online marketplace would never suspend an account (since they have no deadline after the second notice to take action), confusion for third party sellers and marketplaces to practically implement this provision. Thus, the inclusion of the ‘second notice’ would essentially render the bill unusable.

RESONABLENESS V. CONCRETE TIMEFRAME

Yet another proposed change suggests replacing “on demand” in section (bb) regarding collection of information with “within a reasonable time.”[19] While a reasonable person standard or reasonable action of an individual are an appropriate standard in law, in a bill that is dealing with direct timetables, inserting a reasonable time would risk the danger of keeping a third party seller’s posting of counterfeit up for an indefinite period of time and remove the expediency that is important in the effectiveness of this bill.

FRAUD, ABUSE, SCAM AS AN EXCEPTION TO DIRECT, UNHINDERED COMMUNICATION?

An example of this proposed language can be found in state’s version of INFORM Consumers bill previously mentioned above has a proposed clause that states:

The contact information for the high-volume third-party seller to allow for the direct, unhindered communication with the high-volume third-party sellers by a user of the online marketplace, PROVIDED, THE REQUIREMENTS OF THIS SUBSECTION SHALL NOT PREVENT AN ONLINE MARKETPLACE FROM PREVENTING FRAUD, ABUSE OR SPAM THROUGH SUCH COMMUNICATION, including any of the following:(i) A current working telephone number. (ii) A current working email address. (iii) Any other means of direct electronic messaging, including messaging provided by the online marketplace.[20]

The proposed amended language in bold is directly contradictory to the clause before it, noting “direct, unhindered communication,” as it is positing a hinderance to communication.[21] The proposed clause, while perhaps having a good intention, is also impractical. The third-party seller’s information is released to the consumer after the purchase,[22] which could include the seller’s phone number and email address.[23] Practically, how might an online marketplace prevent fraud, abuse or spam from the consumers after the number has been given after a purchase has been made? Although it is inherent on online marketplaces to prevent fraud, abuse or spam in general, I think attempting to add this exception in an unqualified way will give the blanket ability of the online marketplaces to hinder the communication, that in the spirit of the clause is meant to give a consumer purchaser of a product access to the seller to address problems with the product and purchase.

DESTRUCTION OF INFORMATION AFTER 24 MONTHS AND SUPOENA

In some state versions of INFORM Consumers, potential amendments are suggested to require that the online marketplace permanently delete or dispose of this information within 24 months of receipt and not share or disseminate the information to any party without a law enforcement subpoena.[24] This is problematic for two reasons. First, online marketplaces should be collaborating with law enforcement, and they often do without a subpoena or help to make referrals, particularly in this area.[25] Second, this amendment would make it exceedingly hard for consumers to get this information for a lawsuit or reporting to law enforcement if it is destroyed at the two year point. If for example, a consumer is injured or killed by a counterfeit or stolen product, in the majority of states, the statute of limitations for product liability cases ranges from 2-6 years from the time of injury, with some up to 10 to 12 years from the time of sale.[26] This would be a barrier to consumers or law enforcement to get this information.

[1] Kari P. Kammel, Esq. is the Assistant Director of Education and Outreach, Michigan State University, Center for Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection, kkammel@msu.edu. She is an adjunct professor of law at Michigan State University College of Law and is a licensed attorney in Illinois and Michigan.

[2] H.R. 4521, The America COMPETES Act, Jan. 25, 2022, RULES COMMITTEE PRINT 117–31, at Sec. 20213, Collection, Verification, and Disclosure of Information by Online Marketplaces to Inform Consumers, available at https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20220131/BILLS-117HR4521RH-RCP117-31.pdf

[3] See John H. Zacharia & Kari P Kammel, Congress’s Proposed E-Commerce Legislation for Regulation of Third-Party Sellers: Why It’s Needed and How Congress Should Make It Better, 21 U.C. Davis Bus. L.J. 91 (2020), available at https://blj.ucdavis.edu/archives/vol-21-no-1/zacharia-and-kammel.html

[4] Kari Kammel, The Need for a Holistic Approach to Trademark Counterfeiting for the Legal Field, 29 Mich. Int’l Lawyer 3-4 (Summer 2017), available at http://connect.michbar.org/internationallaw/newsletter ; Rod Kinghorn & Jeremy Wilson, A Total Business Approach to Counterfeiting, https://globaledge.msu.edu/content/gbr/gBR10-1.pdf

[5] See generally, Kari Kammel, Jay Kennedy, Daniel Cermak & Minelli Manoukian, Responsibility for the sale of trademark counterfeits online: Striking a balance in secondary liability while protecting consumers, 49 AIPLA Q.J. 201-258 (2021). https://a-capp.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/AIPLAVol49No2pg201to258.pdf

[6] See Kari Kammel, Written Testimony, pp. 12-13, Cleaning Up Online Marketplaces: Protecting Against Stolen, Counterfeit, and Unsafe Goods, U.S. Senate, Committee of the Judiciary, November 2, 2021, available at https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Kammel%20testimony.pdf; H.R. 4521, at Sec. 20213, supra note 2; see also Jay P. Kennedy, Sharing the Keys to the Kingdom: Responding to Employee Theft by Empowering Employees to Be Guardians, Place Managers, and Handlers, 39 J. Crime & Just. 512, 519 (2015)

[7] Kari Kammel, Examining Trademark Counterfeiting Legislation, Free Trade Zones, Corruption and Culture in the Context of Illicit Trade: The United States and United Arab Emirates, 28 Mich. State Int’l L. Rev. 230-33 (2020); see also Kammel, et al, supra note 5 at 230, citing to William Sowers, How Do You Solve a Problem like Law-Disruptive Technology?, 82 L. & Contemp. Probs. 193. 196 (2019).

[8] Sec. 2023, Collection, Verification, and Disclosure of Information by Online Marketplaces to Inform Consumers.

[9] Such as Pennsylvania, Florida and Texas. See generally Senate Bill 944, Florida (January 2022), available at https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2022/944/BillText/Filed/PDF; House Bill No. 888 (Offered January 12, 2022), A BILL to amend the Code of Virginia by adding in Title 59.1 a chapter numbered 55, consisting of sections numbered 59.1-589 through 59.1-592, relating to high-volume third-party sellers in an online marketplace; civil penalty, available athttps://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?221+ful+HB888; House Bill No. 1594, Section 9.4(c), Printer’s Number 2659, Pennsylvania (amendment January 25, 2022), available at https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/PN/Public/btCheck.cfm?txtType=PDF&sessYr=2021&sessInd=0&billBody=H&billTyp=B&billNbr=1594&pn=2659; see also H.R. 5502 stating: (4) ONLINE MARKETPLACE.—The term “online marketplace” means any person or entity that operates a consumer-directed electronically based or accessed platform that—(A) includes features that allow for, facilitate, or enable third party sellers to engage in the sale, purchase, payment, storage, shipping, or delivery of a consumer product in the United States; (B) is used by one or more third party sellers for such purposes; and (C) has a contractual or similar relationship with consumers governing their use of the platform to purchase consumer products.”

[10] https://a-capp.msu.edu/article/a-supply-chain-management-perspective-on-mitigating-the-risks-of-product-counterfeiting/

[11] The covered activities under H.R. 5502(f)(4)(A) Definitions; Online Marketplace.

[12] Id. (Emphasis added).

[13] Id. at Sec (4)(c).

[14] H.R. 4521, at Sec. 20213(a)(1)(A)(i) Bank Account.

[15] Id. at (b)(1)(B) INFORMATION DESCRIBED (ii) (describing notifying if using a different seller to supplier the consumer the product).

[16] See INTA Resolution, Proceeds of Counterfeiting, March 2021, https://www.inta.org/wp-content/uploads/public-files/advocacy/board-resolutions/Proceeds-of-Counterfeiting-Resolution_Final.pdf

Roxane Elings, Combating counterfeiting online: follow the money, Lexology/World Trademark Review, April 27, 2016, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=4a770c59-de93-4ea1-b546-5614cf2ce815 (summarizing follow the money approach in counterfeit cases ranging from the PayPal cases in the 2010s to recent cases in New York against Chinese banks by brands and the IPR Center.

[17] Here, I use the term proactive, which I have also used prior in my testimonies before the Senate. My definition of proactive in this context is any type of vetting, screening, verification, or checks that are done by the online marketplace before they are allowed to be a seller or before a product is allowed to be posted on the marketplace. My colleagues testifying alongside of me from the Internet Association defined it differently—such as taking down suspected counterfeit postings without being asked. See Testimony of K. Dane Snowden, Internet Association, November 2, 2021, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Snowden%20testimony.pdf at page 5. While those activities are still very important in anti-counterfeiting efforts and need to continue, I would term them reactive—dealing with the counterfeit posting after it has already been exposed to the consumer in some way.

[18] Reactive efforts include any action taken after the counterfeit is in the market or the counterfeit post is online and can include (1) market monitoring, (2) notice and takedown, (3) litigation efforts, (4) referring for criminal prosecution, (5) raids, (6) test buys to verify counterfeit, (7) customs enforcement, (8) administrative actions, and (9) and various others.

[19] House Bill No. 1594, Section 9.4(c), Printer’s Number 2659, Pennsylvania (amendment January 25, 2022), available at https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/PN/Public/btCheck.cfm?txtType=PDF&sessYr=2021&sessInd=0&billBody=H&billTyp=B&billNbr=1594&pn=2659. (c) If a high-volume third-party seller does not comply with subsection (b), the online marketplace shall, after providing the high-volume third-party seller with a written or an electronic notice and an opportunity to comply with subsection (b) not later than ten days after the issuance of the SECOND notice, suspend the future sales activity of the high-volume third-party seller until the high-volume third-party seller complies with subsection (b). Id.

[20] (bb) To a payment processor or other third party contracted by the online marketplace to maintain such information, provided that the online marketplace ensures that it can obtain such information on demand within a reasonable time frame from such payment processor or other third party if the payment processor or other third party is able to attain consent from the seller. (Strikethrough is suggested removal and replacement by italicized text).

[21] E.g. House Bill No. 1594, Section 9.4(h)(3), Printer’s Number 2659, Pennsylvania (amendment January 25, 2022), available at https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/PN/Public/btCheck.cfm?txtType=PDF&sessYr=2021&sessInd=0&billBody=H&billTyp=B&billNbr=1594&pn=2659

[22] Id.

[23] H.R. 4521, Sec. 20213, supra note 2, at (b)(1)(A)(ii)(I-II) (noting disclosure of information in the order confirmation message after the purchase is finalized).

[24] Id. at (b)(1)(B)(i)(I-III).

[25] Senate Bill 944, Florida (January 2022) Section (4)(THIRD PARTY SELLER INFORMATION), available at https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2022/944/BillText/Filed/PDF

[26] See e.g. https://www.iprcenter.gov/file-repository/ipu-e-commerce.pdf/view; see also https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ipr-center-amazon-launch-operation-fulfilled-action-stop-counterfeits

[27] See e.g. https://www.findlaw.com/injury/product-liability/time-limits-for-filing-product-liability-cases-state-by-state.html, December 2018