Robyn Mace, 2009

Melamine Case Study

Melamine: Counterfeit Additive in Animal and Human Food Networks 2007-2008

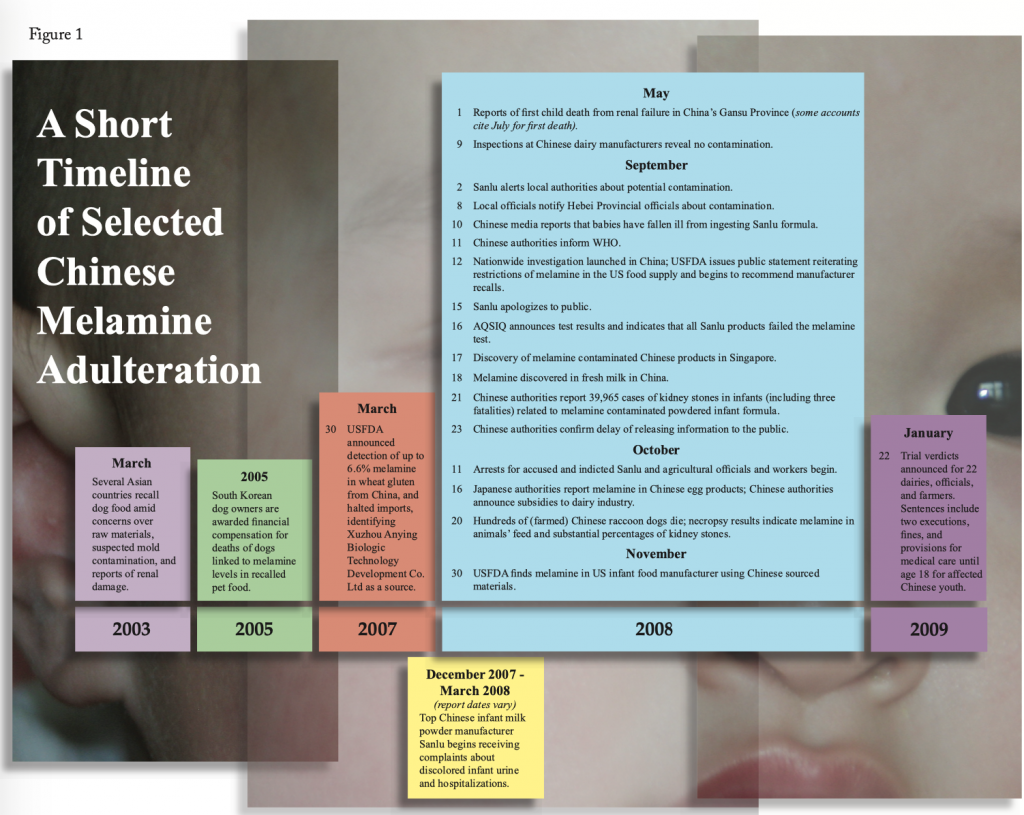

In March 2007, Canadian Menu Foods issued the largest recall of pet food in the history of the United States after it confirmed the presence of the industrial chemical melamine3 in its pet food products through internal testing following consumer complaints (Hansen, 2008) (see Figure 1 for an abbreviated timeline of the Melamine adulteration events). The contamination resulted in a total of over 1000 recalled name-brand products, significant economic losses, and the deaths of perhaps thousands of domestic pets4 (Bhalla et al., 2009; Hansen, 2008). Subsequent testing and investigation in Canada, the US, and China revealed the deliberate introduction, by a Chinese-sourced manufacturer, the unauthorized additive melamine into wheat gluten, to artificially boost measured protein levels in order to improve the quality rating of sub-standard product. At the time, melamine5 was not recognized as a human health threat. However, in 2003-2004, several Asian countries recalled pet foods associated with renal failure attributed to mycotoxin contamination; in 2005, South Korean dog owners were awarded financial compensation associated with the renal-related deaths of 1000 animals (Yhee et al., 2009). Subsequent examination of these nephrological data in 2007 allowed attribution of the 2003-2004 animal deaths to melamine-cyanuric acid toxicosis (Yhee et al., 2009; Bhalla et al., 2009). In June 2007, China banned melamine in animal feed supplies. In October 2008, international news agencies reported that hundreds of raccoon dogs (farm-raised for fur) died after ingesting melamine-contaminated food; necropsy reports indicated melamine in both the animals’ food and kidney stones (AP, 2008).

As early as December 2007, Chinese dairies began to receive customer complaints attributing illness in babies to infant formulas and related dairy products (Chan et al., 2008). In early May 2008, the first related infant death was reported; by June 2008, reports of kidney stones in children became common, with most associated with specific brands of infant formula (Rushworth,2009).The week before the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing, inspectors discovered melamine in milk powder at Sanlu, one of China’s largest dairies and the producer of a leading brand of powdered infant formula. China’s preparations for hosting its first Olympics included traditional bricks and mortar venue development, unprecedented urban renewal, traffic restrictions, and an extensive campaign to establish and ensure food quality and safety standards through regulation and vendor education programs6 (Ellis and Turner, 2008). Local government in Shijiazhuang responded to a request to assist the company in media issues, but did not notify the Hebei Provincial Government of the situation until September 9 (Rushworth, 2009), several weeks after the conclusion of the Olympics. On September 15, Sanlu publicly apologized. By late September, six (6) children had died, over 50,000 had been treated for urinary or kidney problems, and almost 300,000 children experienced some type of renal damage. Over 22 million children were screened for kidney damage. Powdered infant formula products from involved producers were exported to five countries, with other contaminated products exported to even more.

This situation sparked understandable parental and consumer outrage in China, especially in its growing, and increasingly influential, middle class constituents and consumers, who are rapidly developing both expectations about corporate and government performance and the social capital to address important issues. Because the domestically contaminated goods involved infant formula and milk products, products closely associated with beloved children and cherished family life, negative public reaction and outcry towards infant formula and milk products, companies, and the officials responsible for regulating them intensified, as the media broadcast images of children with their parents in lines at hospitals waiting to be tested for renal damage. Significant international media coverage, international backlash against Chinese food products amidst ongoing concerns and recalls of numerous products, tremendous loss of public confidence, and subsequent social and regulatory scrutiny of production practices all followed.

On September 11, 2008,Chinese authorities informed the World Health Organization of the contamination. On September 12, US Food and Drug Administration7 (FDA) officials issued public statements reiterating US regulations restricting melamine in the US food supply8, and began to recommend manufacturer-issued recalls of products with ties to Chinese dairy products. Melamine was detected in Chinese-manufactured candies, instant coffee, and other products. The European Union has banned Chinese milk products since 2002, and on September 26 extended the ban to all Chinese composite products containing milk or milk products intended for infants, including candies, biscuits, chocolate, toffee, or cakes (ECDC, 2008). There is no definitive report as yet that describes the geographic distribution, extent of contaminated products, health impacts, influence on consumer confidence, and economic and social costs of these events.

Domestically, more than 30 Chinese dairies were implicated in the contamination, over the course of official Chinese investigations in 2008-09. Local government officials were fired; at least 60 persons were arrested and 21 have been tried. Sentences included two (2) executions (a farmer-producer of melamine, and a broker- adulterator) and life imprisonment for the former chairperson of Sanlu. Culpable dairies were ordered to pay US $ 16 million in cash settlements to the families of affected children and to fund medical care until the children turn 18. Willful contamination with melamine was the second major Chinese infant formula quality scandal in this decade; in 2003, widespread unsafe practices and sub-standard nutritional value of 55 different infant formulas from 40 companies were found responsible for 12 infant malnutrition deaths (Chan et. al., 2008).

Threats to food protection and defense stem from both deliberate and unintentional actions and conditions; it is important to distinguish between inadvertent or accidental adulteration of product and deliberate contamination designed to misrepresent the product or disguise the adulterating ingredient(s). Unintentional pathological corruption may be due to contamination during processing, food transportation, storage, or food preparation and handling. While emergency responses follow similar procedures regardless of the mechanism, and both types of threats present under-recognized risks to consumers, supply chains, and markets, the systematic adulteration of food products seems the more compelling potential health and economic concern.

Food-borne illnesses, contamination, adulteration, and subsequent investigations into their sources may threaten markets for general commodity types (e.g., produce), commodity classes (e.g., lettuces), and specific products (e.g., spinach9). Suspicions, recalls, and uncertainty about specific or classes of products can depress or eliminate sales for all producers of that product for indeterminate time frames. Inability to respond to and recover from disruptive or disastrous situations is a major cause of business failure.This scenario is particularly threatening for small, price-sensitive producer-purveyors of perishable foods. Failures in small producers can disrupt local markets and have international commodity, price, and production repercussions.

Deliberate industrial contamination (as in the melamine scandals) presents significantly different challenges than do individual instances of adulteration during production or at the point of sale or distribution. The most recent two melamine scandals intensified and validated domestic and international concern about the quality, integrity, and safety of China’s food products. As a result of public health and consumer concerns, national legislative and regulatory agencies, international food corporations, and regional and local producers began to reconsider how to ensure the safety of food supply production networks. Responding to the widespread illness, enhanced domestic and international scrutiny, and the development of a burgeoning domestic consumer awareness and advocacy movement, Chinese officials have enacted several pieces of legislation designed to improve food safety and oversight, notably the 2006 Agricultural Quality Safety Law and the 2008 Draft Food Safety Law.

The Draft Food Safety Law made sweeping provisions for governmental oversight and identifies the Ministry of Health as the primary food safety oversight entity (Ellis and Turner, 2008). Additionally, the law enhances requirements for corporate and government reporting, recall, and investigation activities and protections for corporate and government reporting, recall, and investigation activities and protections for whistleblowers.

Much of the focus of these efforts involves establishing a sanitary infrastructure in China and building industrial and consumer cultures that recognize and value food safety and protection initiatives (for both commercial and public health reasons). In the US and Europe, this infrastructure has developed over time, concurrently with the growth of the agriculture industry.

The Food Fraud and Counterfeit Triangle: A Model for Understanding and Assuring Food Protection and Defense in International Food Production Networks

Producers, consumers, and markets comprise a vast web of production and consumption of global food supply chain networks. Complex and variable systems of voluntary and regulated domestic and international product standards, processing capacities, and labeling characterize the international trade in agricultural commodities and food products. Within these systems of interaction, there are numerous agencies, interests, and conditions that influence the global and local risks inherent in and associated with the production and distribution of ingestible products (i.e., industry and professional associations, industry service providers, consumer advocates, and health and safety professionals). Constituent members of these extended supply chain networks and markets have vested interests in the satisfactory outcomes of food market exchanges, and consequently, if properly motivated and constructively engaged, can exert influence to reduce opportunities for food-related vulnerabilities, failures, and public health and safety events. Effective formal and informal social control mechanisms in regulatory and production supply networks are necessary to deter and mitigate potential disruptions from product quality issues.

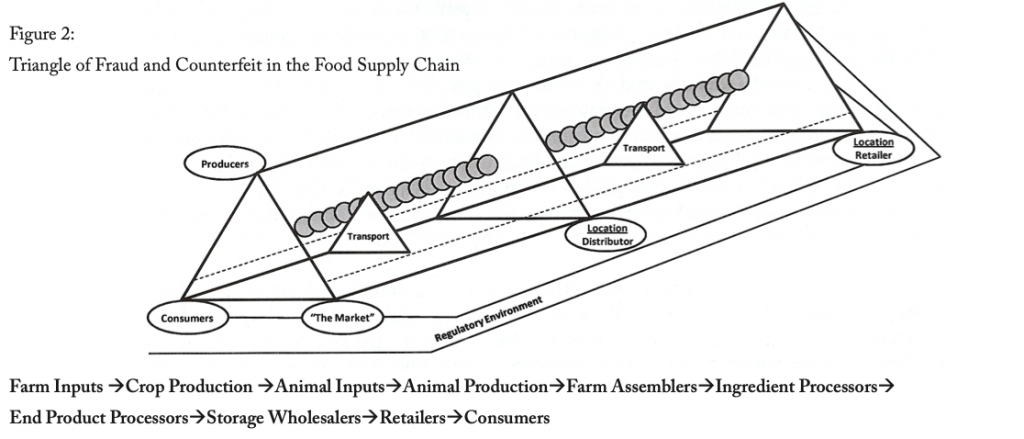

The intersection of food fraud and counterfeit is a modified crime triangle that depicts the basic components of food production through the supply chain (see Figure 2).

Interaction of the three elements (producers, consumers, and markets) provides the context within which food fraud and counterfeiting (as well as legitimate transactions) occur. Basic food markets are created through exchanges between producers and consumers. Markets and transactions are generally regulated through context- specific combinations of voluntary and externally-imposed controls over quality, integrity, and safety. As food production and distribution networks grow larger, they encounter, (and if accepted in new markets) comply with, and become embedded in broader geographic market rules and regulations. Identifying commonalities in behavior patterns in each of the triangle’s components allows consideration of the appropriate application of formal and informal pressures to address and eliminate potential hazards in food supply networks, including adulteration and counterfeiting.

Agriculture and Food Producers: Small Farms to Multinational Corporations

Every market presents opportunities for bad actors or transaction fraud, especially marginal or unregulated markets or those with consumers who have little awareness or market influence. Inclement weather, climate change, diseases or pests, quarantine, environmental contamination, civil unrest, port closures, market competition, capitalization, and trade barriers are among the challenges to stability and profitability of food production in global markets. Market differentials in regulation, professional knowledge and skills, technology, and oversight can have a huge influence on a food system’s susceptibility to inadvertent or deliberate contamination. Poor handling and storage practices; health and hygiene of producers, processors, and facilities; and lack of developed and enforced production standards all contribute to the potential introduction of unsafe additives or ingredients in food products.

China’s meteoric rise to become the world’s leading food producer has occurred in the context of dwindling arable land, increased production pressures, small farm operations, and cash economies with limited transactional records,all in the absence of regulation and enforcement.These factors intersect with limited producer and consumer awareness of modern industrial production or hygienic practices designed to identify, minimize, and eliminate threats to food product quality. A scarcity of knowledge about agricultural routines combined with production pressures can lead to dangerous practices—unsafe fertilizers, restricted additives, chemical protein shortcuts, and products with ingredients that are not as advertised; the consequences may not be apparent immediately, or for some time.

Accountability and transparency in production systems are essential to provide product safety and assurance. Self-regulation contributes to brand and product market share protection through consumer confidence and satisfaction. Recognizing that the fundamental quality of a product is a determining factor in consumer purchasing decisions, food producers have few incentives to repeatedly sell substandard or harmful product to local, long- term consumers. In more regulated food markets such as the European Union and US, government and industrial regulation and internal corporate and producer governance articulate and provide oversight to markets; however, external regulation alone does not ensure the quality of production or product. Governance systems oversee a firm’s organization, assets, spending, personnel, and inventory. Environmental demands for adaption can promote opportunities for strategic leadership to enhance visibility in supply chain network operations, while reducing the variability and vulnerability inherent within them.

Industry associations and professional organizations exert strong normative influence on legislative initiatives, industry education, and production standards. Using a collaborative approach that focuses on voluntary rather than mandatory standards, these organizations actively identify and promote best practices and standards, positing that thoughtful and functional recommendations are better for business. These organizations have contributed to the development of numerous production standards and strategies, as well as testing technologies and protocols designed to identify and eliminate threats to food safety. Industrial production guidelines and industry-specific working groups strove to raise concerns about environmental and industrial contaminants that may interfere with the production of quality raw and processed foods.

In addition to compliance with product, informal, and formal market standards, some companies elect to voluntarily exceed industrial and production standards and measures. Rising producer and consumer concern over sustainable production and livable wages for workers has led to a variety of certified product, company/ cooperative, and supply chain initiatives, as well as support for fair-trade practices and wages.These industry leaders work actively with government officials to continually test, refine, and improve processes, training, inspection, and auditing practices. Industry and professional organizations also inform corporate culture through their membership, and can generate and promulgate best practices in terms of growing, managing, harvesting, cleaning, processing, and other aspects of bringing agricultural products to market. Given that legislation, enforcement agency capabilities, and legal mechanisms vary according to market, social, and political factors, industry and professional associations must continue to fully participate in the development and promulgation of production standards and technologies.

Individual and Commercial Consumers

Counterfeiting and product fraud have traditionally been associated with currency and luxury items. The recent trends of comestible and household product counterfeit and fraud introduce several important concerns for consumers and producers, most notably public health and safety and social trust in markets. For consumers especially, critical issues relate to product ingestion, essential or discretionary product demand, and volition in selecting product attributes (i.e., having an expectation of ingredients and materials). The willingness of consumers to purchase potentially counterfeit goods due to cost, false-brand preference, or other reasons is also of concern in both comestible and non-comestible product markets. Food fraud and counterfeit raise significant challenges for regulators, public health officials, and food producers since these products are frequently and increasingly distributed through apparently legitimate markets and outlets.

Consumer and producer awareness and concern about food integrity and safety issues varies according to cultural, economic, and political factors, as does the ability of the market and regulators to provide protection for consumers. Consumer awareness of and tolerance for counterfeit products has received only limited academic attention, although recent food and product safety scandals in China have eroded that country’s domestic trust in both manufacturers and regulators.The 2008 Chinese Consumer Survey indicated that substantial majorities of respondents considered safety and quality to be among the most important concerns influencing purchase decisions, especially for medications, fresh meat and fish, and produce; almost two-thirds reported wanting more information about ingredients and food sourcing (IBM, 2008). Until consumers recognize a risk from counterfeit or adulterated products, very little awareness or advocacy can or will occur, nor will there be corresponding pressure on institutional actors. The melamine scandals seem to have precipitated widespread consumer and media awareness, both domestically and internationally, that has already influenced Chinese regulatory and production controls.

The Marketplace: Regulation and Governance

Regulation involves externally imposed operational requirements; governance refers to internal organizational strategies and processes organized to allow firms to meet production and regulatory requirements. At the international level, there are several non-governmental, non-profit, and private sector organizations that heavily influence international food safety issues, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the World Bank. These organizations have both legal and moral authority, exert issue leadership, and can direct financial, relief, and other programs to address public and health safety issues related to food and food products.

The WHO and FAO jointly administer the Codex Alimentarius (established in 1963), international standards for food and animal production and safety. The WTO’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures (1995) encourage free trade, establish processes to institute food and feed production standards (as countries are required to bring their national laws in compliance with WTO standards), and provide guidelines for the resolution of disputes relating to regulatory differences in production and consumption markets. The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) is the international intergovernmental standard setting agency for domestic animal health. In the US, the majority of regulatory responsibility for food products falls to the FDA, although there are areas of overlap (and gaps in coverage) with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and substantial cooperation with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

China’s food system presents a major regulatory challenge since it is so decentralized— 70 percent of food processors employ fewer than 10 workers on farms of two (2) acres or less (Ellis and Turner, 2008). Transparency and accountability are relatively new concepts in China’s cash-based transactional markets, comprised of numerous small producers, as there has historically been little reason to link the elements of production with end consumption (i.e., farm-to-fork). Animal farmers feed their livestock according to what will reap the highest profit, with little knowledge of postproduction consequences; feed may include industrial compounds or human or animal waste (OECD, 2007). Farmers may medicate sick animals to improve their appearance for sale or slaughter. In areas with high pig or chicken densities, this practice may be intensified by the fear of loss of stock or market share through culling diseased animals, given that the government provides little or no compensation to farmers for public health–mandated culls (Ellis and Turner, 2008). No amount of education or training can overcome these structural obstacles; they must be simultaneously addressed at the regulatory and production levels. Institutional and regulatory development in China has been significantly outpaced by economic development, particularly with respect to agricultural production.

Import and Export Food Safety Bureau Director General Wang Daning indicates that 12,700 Chinese food processors have licenses to export (Rice, 2007). There are approximately 600 enterprises using the organic certification logo to sell domestically in China and 12,000 companies have organic permits to export (Ellis and Turner, 2008). Since a growing percentage of China’s exports to the US are food ingredients, products, or additives/preservatives (e.g., wheat gluten, lactic acid, and ascorbic acid), these discrepancies in food markets raise concerns about Chinese food safety. These concerns are echoed among international consumers, food companies, and regulators, as China continues to expand its share of international agricultural and food product markets.

In all,82,000 shipments of food products and ingredients were exported from China to the US in 2002. By 2006, this number had risen to 199,000 shipments; FDA officials estimate food shipments from China totaled 300,000 in 2007 (Knox and Magnum, 2007). In July 2007, China’s State Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) admitted that half of all food producers had improper licenses, and that 164,000 had no license at all (AQSIQ, 2007). Quality and process assurances in low-margin, highly competitive markets will require government regulation and incentives as well as consumer and industry pressures.

In complex industrial systems, firms must satisfy external demands from customers, partners, and regulators, while organizing and overseeing internal functional responsibilities. All producers are constrained by regulatory requirements and internal organizational governing systems and structures. Compliance requires company participation and resources; regulation can represent a significant challenge to firms, particularly as rules change to adjust to industrial and other circumstances. Industry, regulatory, and third party efforts to enhance operational controls over inadvertent or deliberate production contamination are critical to improving food quality and assurance.

There are numerous ways to bypass internal production and third-party quality controls and regulations (i.e., falsification of data, substitution of inferior products) in the absence of continual, direct oversight. Inspections to catch violations of quality or administrative errors in paperwork generally only address a small percentage of product volume. Inspection efficacy can be enhanced by using risk-driven or criteria-based inspection, rather than a random or percentage-based approach. Although post-hoc inspection does not constitute prevention; selective use of authentication and traceability technologies can contribute to effective pre-identification and integrity assurance programs at the production, domestic, or international level.

Prevention and Resilience: Crisis and Opportunity in Global Food Supply Network Protection and Defense

As demonstrated by the Chinese melamine scandals, counterfeiting in the food supply chain is a deliberate decision-making and behavior process, generally in conjunction with or as a consequence of legitimate business activities. Counterfeit and fraud may be features of developing consumer and manufacturing markets—and of more articulated health and safety concerns in mature economies.They may also be an indicator of pervasiveness of economic or political corruption and/or a lack of consumer alternatives or sophistication (as well as a reflection of sophisticated packaging technologies, distribution channels, and abilities of products to “pass” as authentic). These types of activities will continue to be profitable until their costs are too great for the counterfeiters, either through production controls, consumer demands, government oversight, or criminal penalties. Driven by individual and collective level actors and activities, the majority of labor is largely unskilled, replaceable, operational personnel, while aggregated transactions are geographically dispersed in both production and consumption. Geographic transshipment patterns for interdicted food items suggest this as a key strategy to avoid inspections and to evade regulatory requirements. The temporal lag from the discovery of a food-related illness to its identification and resolution (determination of cause,subsequent product tracking and recall,casualty treatments,risk communication/ consumer notification, etc.) is of variable length, depending on detection and reporting capacity and mechanisms, traceability systems, and emergency response protocols. International products present great challenges to the epidemiological processes, particularly those from producer countries with inconsistent or non-existent regulatory and production standards. These characteristics dilute the effectiveness of oversight systems.

Intervention strategies can and should be developed and targeted to specific characteristics of the crime triangle elements—producers, consumers, and product distribution networks—based on consideration of the social and economic harm and the range of potential alternatives. Using enhanced cargo and supply chain tracking and inspection to identify illicit goods, their transit methods and routes, and the method of entry into the system may also reduce the volume of sub-standard goods. Strengthening existing legislation and penalties to more vigorously discourage and punish offenders may assist in disrupting trade by interdicting the methods of production (equipment, skilled workers, raw materials). Best practices and benchmarking for prevention, detection, and resilience activities include ongoing awareness, education, and training about safe food production and handling procedures for producers and consumers, and regular, meaningful communication with stakeholders and at-risk groups by regulators and industry producers. The process should be continuous and iterative, integrating new findings and technologies into standards and training.

In terms of food supply network protection, defense, and resilience, three operational level principles are essential to product integrity and quality control: visibility, authentication, and traceability. Visibility refers to the availability and usefulness of information regarding the origins, status, location, or conditions (e.g., temperature) of a product or particular shipment. Authentication confirms that a product originated from a genuine manufacturer or is genetically or chemically as identified and presented. Depending on the product, authentication may occur at critical junctures, or choke points, during the manufacturing process, or continuously through the processing where authenticity may be compromised. Traceability capabilities extend the basic concept of visibility throughout the entire production and distribution process within and throughout the supply chain, from initial product components to ultimate distribution points and end users.

Technology plays a central role in the capabilities necessary to generate accurate, timely, and actionable information. The main goals are prevention of contamination, speed of incident detection, forensic investigations, and product intervention or removal to prevent future injury.It is not possible to eliminate all potential contaminants from the global food supply network. However, it is possible to systematically and continuously use procedures, technology, and auditing to identify potential contaminants at the earliest stages in food processing and production, and to rapidly trace the production source.

A number of mechanisms are used to authenticate products, including packaging techniques such as holograms, barcodes, and radio frequency chips. Immunoassay and chemical tests may also be used to detect active ingredient concentrations and contaminants. Historically, these types of tests have been expensive, although technological advances and market demand are beginning to make them more affordable. Authentication efforts may also be complicated by the sheer number of products that a company produces and the availability of standard assays or suitable tests to detect unanticipated ingredients.

Some authentication measures can facilitate visibility and serve functional traceability purposes within the supply chain. Increasingly sophisticated detection and monitoring systems are heavily reliant on technologies. Due to the expense and effort required to realize them, technological investment must be leveraged by integration with other operations level processes and functions, without introducing undue delays or disruptions in production or processing. While technology can facilitate vital business functions, it cannot perform them. It presents a powerful tool to address supply chain and security management issues, yet technology is not a stand-alone security solution. It requires on-going investment, employee training, and managerial oversight, coupled with the recognition of the dynamic ability of counterfeiters and fraudsters to quickly change their activities in response to prevention strategies and product interdiction.

With operationally focused and functionally aligned metrics, firms can generate and use this information for incident and crisis-management and to promote early intervention to mitigate disruption and damage. Combined with requirements for enhanced corporate record-keeping and reporting,this puts a great deal of emphasis on information technology and IT support throughout the organization and the supply chain. In a rapidly evolving global economy or challenging circumstances, it is easy to understand that large firms may be better able than small firms to develop and integrate specialized responses to environmental demands, including regulation and enhanced security measures, based on sheer demographic and resource capacity. Implementing or upgrading safety and security procedures can be a financial and resource burden to smaller companies with smaller operating budgets and lower cash reserves. Business incentives and regulatory schemes must recognize and make provisions to support small producers in these efforts in addition to procedures to ensure compliance.

Conclusions

Perhaps the most important lesson from the Chinese melamine events is a new understanding and appreciation for the exceptionally broad span of products and sources (and vulnerabilities) within global food supply chains, and the pernicious effect throughout of deliberate (albeit not intentionally harmful) product adulteration. The duration and scope of melamine use as a common food and feed additive indicates that it was a systematic and accepted practice, as there were no compelling reasons to stop it. Since the discovery of the national and international health and economic consequences, China has begun to develop an infrastructure to maintain its market leadership and develop and solidify its brand; safety and quality will be essential drivers of this transition for both industry and regulation. The influence of domestic and international consumers in this process is likely critical in this transformation, as social concern over the quality and integrity of products from China and elsewhere is heightened.

Preventing every incident of food counterfeiting or contamination is not realistic, although it is possible and reasonable to reduce specific and identifiable risks through the systematic application of risk management principles, technology, and good production and management practices. Laws alone do not ensure the integrity, quality, or safety of the food supply, nor can industry oversight completely protect consumers from contamination in the food supply chain. Food integrity and quality cannot be forced into a system through testing; rather they are achieved through multiple, concentric processes designed to create broad, consistent standards and coverage.

Addressing these issues will require corporate, regulatory, and consumer awareness and efforts on an international, multi-jurisdictional scale. Governments, corporations, and consumer groups must collaborate to educate consumers about the availability and potential safety concerns of counterfeit goods. Successful efforts to strengthen food product standards and to educate producers and the public will necessitate articulated and assured voluntary and mandatory standards, overlapping and redundant auditing and inspection of information and processes, and continuous monitoring and feedback on production exceptions and emerging threats. There are abundant opportunities for collaboration in cross-disciplinary research to continually improve food protection and defense activities and measures in domestic and international food supply network systems.

Corporations and consumers must acknowledge the realistic costs of agricultural production to reduce subtle pressures toward corruption and environmental or production degradation. Narrow profit margins combined with local and international demand for cheap prices may also pressure food processors to evade costly quality control laws. Small and subsistence producers and processors have little or no formal education in safe food handling and processing practices, may not be able to afford safety equipment, and are not identifiable by product or facility within supply chain networks. Furthermore, corruption and malfeasance can undermine safety ratings of a particular batch of food from a specific company even within voluntary or third party-verification processes. Oversight systems are only as strong as their weakest links.

Integrated design, planning, and governance should be addressed at the strategic social planning and industrial production levels to identify how technologies can support tactical decisions and be productively integrated with existing operations level production and manufacturing processes. Firms must understand market and supply chain member conditions to actively develop, implement, and monitor business protection and defense strategies and activities. As markets continue to evolve and supply chains extend, food industry producers, consumers, and regulators must become more adept at identifying and intercepting potential threats to quality, integrity, and safety.

References

Associated Press (AP). (2008). China: 1,500 raccoon dogs die from tainted feed. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/27284840/

Bhalla, V., Grimm P.C., Chertow, G.M., & Pao, A.C. (2009). Melamine nephrotoxicity: An emerging epidemic in an era of globalization. Kidney International, 75, 774-779.

Chan, E.Y.Y., Griffiths, S.M., & Chan, C.W. (2008). Public-health risks of melamine in milk products. The Lancet, 372(9648), 1444-1445.

Clarke, R.V. (1997). Situational crime prevention: Successful case studies. Guilderland, NY: Harrow and Heston.

Clarke, R.V., & Eck, J. (2005). Crime analysis for problem solvers in 60 small steps. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Closs, D. (2005). Dimensioning a security supply chain. Proceedings of the Institute of Food Technologists’ First Annual Food Protection and Defense Conference, November 2009, Atlanta, GA.

Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.ift.org/fooddefense/22-Closs.pdf

Ellis, L.J., & Turner, J.L. (2008). Sowing the seeds: Opportunities for U.S. China cooperation on food safety. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.wilsoncenter.org/topics/pubs/CEF_food_safety_text. pdf

Embarek, P.K.B. (2009, February). Melamine contamination of milk: WHO perspective on food safety issues. Presentation to 4th Dubai International Food Safety Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). (2008). Provisional ECDC Public Health Impact Assessment. October 1. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/ healthtopics/Documents/081001_Melamine_Health_Impact_Assessment.pdf

Hansen, S.R. (2008). The 2007 United States Pet Food Recall. Clinical Toxicology, 46(5), 360.

International Food Information Council Foundation (IFICF). (2008). Questions and answers: Melamine as a contaminant in food. Food Safety and Defense. December 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.ific.org/publications/qa/melamineqa.cfm

Knox, R., & Magnum, L. (2007). As imports increase, a tense dependence on China.

Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=10410111

IBM Global Business Services. (2008). Full value traceability: A strategic imperative for consumer product companies to empower and protect their brands. Somers, NY: Institute for Business Values.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2007). Environmental performance review: China. Paris: OECD.

Rice, J.M. (2007, October 23). Food safety smarts. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119308829800667563.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

Rushworth, M.F. (2009). Melamine and food safety in China. The Lancet, 373(9661), 353.

State Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ). (2007, July). Further Strengthening Food Production and Processing Small Workshops and Supervision Work: Three Prominent Regulatory Systems to Ensure the Quality and Safety of Food.

Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.aqsiq.gov.cn/zjxw/zjxw/zjftpxw/200707/ t20070711_33419.htm

United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA). (2009). Melamine contamination in China. Retrieved September 28, 2009, from http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm179005.htm

Yhee, J.Y., Brown, C.A., Uy, C.H., Kim, J.H., Poppenga, R., & Sur, J.H. (2009). Brief Communications: Retrospective study of melamine/cyanuric acid-induced renal failure in dogs in Korea between 2003 and 2004. Veterinary Pathology, 46, 348-354.

2019 Copyright Michigan State University Board of Trustees.