Joseph Longo, 2019

Introduction

Intellectual property rights have had a space in China for centuries, though, they were not afforded serious legal consideration until the mid-1980’s. With a complex and comprehensive bureaucracy dedicated to protecting both foreign and domestic intellectual property, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), on paper, is very similar to the West. Yet despite this, violations of intellectual property are still common and, in many ways, normalized in China. One in three North American corporations allege that Chinese-based companies have stolen their intellectual property in the past decade, while one in five allege that it has happened in the past year.[1] Recent estimates by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) reveal that nearly 90% of all seized counterfeit goods originate from China.[2] For context, the total trade of counterfeit and illicit goods amount to as much as 3.3% of global trade, and 6.8% of EU imports from outside countries.[3] This paper seeks to explain why the PRC is a breeding ground for violations of intellectual property. First, it will provide a historical context as to how intellectual property rights laws and policies were enacted in the PRC. Then, it will dive into current assessments of China, including the allegations of trade theft, patent protection and the vast counterfeiting enterprises. From there, this study will examine each of the major actors involved in Chinese intellectual property policy, namely outside agencies, the national Chinese government, the local officials, and general population. Finally, the paper will conclude by using international relations theory to explain the current environment for intellectual property.

Before beginning this research, one must understand what intellectual property rights are and how they have become important in the modern age. As an intangible asset, intellectual property refers to inventions, artistic works, symbols, designs and other creations of the mind.[4] Similar to any other property right, these protections allow for creators to benefit from their works. Depending on how it is expressed, intellectual property is generally divided into one of four categories, including patents, trademarks, copyrights and trade secrets. Patents protect an invention and generally last for 20 years, though when that timeline legally begins is dependent on the country for which the patent is granted.[5] Trademarks protect a brand, ensuring that a good is produced by the correct manufacturer. Excluding unique circumstances, trademarks will continue to last for as long as the fees are paid.[6] Copyrights protect artistic creations, such as music, literature, art, and most noteworthy, computer code.[7] Finally, trade secrets encompass confidential information that make one firm more competitive than another.[8] While each country maintains its own laws and policies regarding intellectual property, the international community abides by a series of conventions administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization. These include the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Paris Convention), the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Berne Convention), and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Intellectual property rights are essential for protecting and promoting innovation. From an individual perspective, intellectual property rights ensure that creators, or those that invest in the creation of a good, earn their deserved credit and remuneration. From a societal perspective, these rights promote innovation and growth. Guaranteed protection and uniform law provide greater incentive to develop new products, which in turn contributes to a more advanced economy. The OECD found that “stronger levels of patent protection are positively and significantly associated with inflows of high-tech product [and] expenditures on [research and development].”[9] Intellectual property also serves as one of the many metrics for measuring a state’s growth. For example, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) ranks state innovation by comparing the number of patents filed in respective countries.[10] In essence, intellectual property is the backbone of state advancement. Without uniform laws that effectively protect these intangible rights, societies inevitably suffer from suboptimal innovation.

Trademark counterfeiting is another violation of intellectual property, but one with very different effects. In many circles, counterfeit products bring to mind the notion of imitation luxury goods, such as purses, shoes and other accessories. As such, a common misunderstanding is that the only victims in the cases of counterfeit goods are multinational corporations. However, experts estimate that only 5% to 10% of all counterfeits are of a luxury good,[11] and only half of all counterfeit goods are of clothing, accessories or shoes.[12] The remaining counterfeit products include infant formula, vaccines, prescription drugs, consumer goods, and aftermarket parts for everything from automobiles to aircraft carriers, to name just a few.[13] The dangers of such counterfeits are just as varied as the products themselves, with notable examples being lethal amounts of melamine in infant formula[14], faulty aftermarket airbags[15] and even counterfeit N95 masks during the COVID-19 pandemic.[16] Disastrous consequences are not only present from a public health standpoint, but financially as well. New York City and Los Angeles both estimate that they annually lose $1 billion and nearly $500 million, respectively, in city tax revenue due to counterfeits. [17] [18] Additionally, because the trafficking of counterfeit goods is so profitable, with estimated values higher than $500 billion in worldwide trade[19], money from counterfeit goods have been found to finance corrupt governments, organized crime and even terrorism.[20] Though it is true that brands do suffer from counterfeit goods, more importantly, the counterfeiting enterprise poses a stark danger to the public welfare.

In short, violations of intellectual property have far-reaching consequences beyond just large corporations. They stymie knowledge advancement and economic growth, and their profits can be utilized to finance other illegal crimes. As a result of a more globalized world, as well as the advent of third-party e-commerce sites, intellectual property right laws are more important now than ever before. For these reasons, this paper seeks to explore how they were developed in China, and why China has become the breeding ground for intellectual property right theft.

History of Intellectual Property Rights in China: Developing Laws to Appease Domestic and Foreign Interest Groups

This section will discuss the development of intellectual property rights in China, both in a historical and a legal sense. By chronicling the development of these policies, as well as how intellectual property has manifested itself in Chinese history, this section will explain how Chinese IP laws were realized from a Western influence but catalyzed by a domestic constituency. Additionally, this section aims to describe how Beijing has used national policymaking as the platform for intellectual property reform, yet has failed to enforce these policies in many localities. As a result, the image that Beijing continues to paint often masks the reality that brand owners and innovators face from local officials. This understanding is vital for both international policymakers as well as brand owners, both of whom have attempted to change China as a foreign influence.

Branding: Ancient China to Present

Though modern intellectual property policy is a relatively new concept to China, developed only in the last half-century, intellectual property in its simplest definition can trace back thousands of years in China. Trademarks, as discussed, are the brands, logos and “marks” used to describe the origin of a product, claiming an artist’s ownership and ensuring its quality and place of origin for authenticity.[21] By this definition, some of the world’s earliest known trademarks are attributed to Chinese potters and sculptors. Marks of origin on Chinese pottery are identifiable from as early as 2700 BC, which experts believe were some of the first branding practices.[22] In the Shang Dynasty (2000-1500 BC), the crests of kin groups (zu) were used to identify the creators and quality of pottery, wine vessels, fencing and cooking pots.[23] While these brandings were all carved into products, the first known use of Chinese stamping procedures began in 221 BC, continuing from the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) to that of the Han (206 BC – 200 AD), Tang (618 – 906 AD), and Song (960 – 1279 AD), where family names were used to delineate product origin, the government imposed product branding, and product labels with a symbolic logo and text were created.[24]

The development of branding in China has a long history, though most Western industry leaders and policymakers would argue that this history is far removed from the legal concept of Chinese trademarks today. This evolution, however, has created implicit meanings behind what a brand name means in China. Unlike the relationship between English and European languages, for example, Mandarin Chinese belongs in an entirely different language family.[25] Direct translations between Mandarin and English are infrequent, and instead, words are developed around similar needs and definitions, meaning that dictionary translations often do not represent the social and cultural connotations of each word.[26] As such, there is value in understanding how the very meaning of a brand is perceived in China. While the definition of a brand in the West is straightforward, representing a “name, term, sign, symbol, or design […] intended to identify the goods and services of one seller […] and to differentiate them from those of competition,”[27] this same word has at least four Chinese terms that relate to this definition.

The oldest Chinese terms for a brand originate from the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911 AD), including biaoji and hao.[28] Each represents a distinct cultural category. Most similar to what is known as a brand today, biaoji symbolized the name or area of a merchant or group of merchants that sold the good.[29] Hao, on the other hand, had a much more cultural context. Hao goods had to be trusted, with a long history and great reputation. More importantly, they had to represent the spirit and social values of Chinese culture, named after the image of the Chinese nation. These brands had to have honest and fair values, with positive contributions to the public welfare.[30] Examples of hao include the Tong Ren Tang medicine store, which originated in 1669,[31] and Pian Yi Fang, a roast duck restaurant from 1416.[32] Both are still prominent brands today.

Additionally, two other words conveyed a meaning similar to that of a “brand,” including lei and gongpin. While biaoji and hao were used for objects ranging from medicine to writing papers, they did not necessarily distinguish quality between commodities. Instead, they generally described a product line or merchant group.[33] For goods that required quality-based differentiation, such as teas, rice and liquor, the term lei was used to indicate a quality grade.[34] Gongpin, on the other hand, were goods created specifically for tribute to the emperor. These premium goods, consisting of combs, shoes, medicines and foods, would be given the gongpin status upon receipt of the tribute, distinguishing these craftsmen from others in the region. Though they would not produce the same quality of good for typical consumers, their acceptance as a royal supplier would elevate their merchant status, acting as a halo effect for their other goods.[35]

More recently, the terms used to describe a brand in China today would be paizi, pinpai, or in some cases, mingpai or chiming shangbiao. The terms pinpai and paizi both originate from the late Qing Dynasty, when brands began to have a legal status.[36] Under British imperialism, the Qing Dynasty faced immense pressure to develop trademark law to protect British brands, and as a result, in 1904 the Qing Dynasty disseminated a set of provisional regulations, titled “Experimental Regulations for the Registration of Trademarks.”[37] These regulations marked the first formal trademark laws in China and were later developed into a stricter code during the Chinese Republican Period, again under the pressure of British forces. As a result, the terms pinpai and paizi became normalized, with pinpai being used in more formal, often written, situations and paizi in a more vernacular context.

Beginning in the 1990’s, the term mingpai became popular to describe “established brands.”[38] Though there is no exact distinction between a pinpai and a mingpai, mingpai companies generally have the following three qualities: high visibility, high quality, and a high market share.[39] Additionally, there are important legal and societal distinctions between mingpai and zhiming shangbiao, or“established brands” and “well-known trademarks.”[40] For example, Wang Mazi scissors, a brand created in 1651, would certainly be categorized as a hao and biaoji, but is generally not considered a paizi or pinpai by contemporary Chinese consumers.[41] These minute distinctions are important, as they form the basis of expanded legal protections and social distinctions.

Though to many outside actors these distinctions are irrelevant, it is important to understand how a brand and its associated image is viewed in China. The existence and evolution of such varied terms highlights the different conceptions of a Chinese brand, especially when in comparison, the West’s notion of a brand is fairly straightforward. Additionally, the varied terms represent the important role that culture plays in organizing the marketplace, a degree to which the West is largely unfamiliar with.

The Development of Intellectual Property Law in a Post-War People’s Republic of China

The Chinese Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. This came after a near 40-year civil war, Japanese occupation during the Second World War, and what was later known as the “Century of Humiliation,” a 100-year period where China was ravaged by foreign imperialism and mass opium addiction. The powerhouse that China had been for centuries was no more, leaving Mao Zedong with nothing but an enormous population to rebuild a country. In the 70 years since this declaration, China has built itself into one of the world’s strongest nations, with a backbone of intellectual property law to sustain its growth. Yet, even with these policies and procedures in place, China continues to violate intellectual property on a massive scale. This section will analyze the history of Chinese intellectual property policies, paying specific attention to those of trademark and patent law. By understanding how these were developed, this section will shed light on the challenges that the Community Party has had to overcome in order to establish intellectual property right laws, as well as the consistent theme of a lack in

Following Mao’ success in the Chinese Civil War, the Communist Party recognized the need for science and technology in rebuilding a country. This recognition, however, also came with several contradictions. Mao’s constituency was a large, generally uneducated peasant class—one that had grown in opposition to the college-educated urban elites.[42] Further, the idea of protecting technological innovation as private property ran opposite to the very ideals of socialism. As such, the Mao government developed a model of scientific and technological development in which innovation belonged to the public. As one electrical engineer described Mao’s call to innovate for the community, his “blood was burning. [The] country had been poverty stricken for so many years. [He] was willing to sacrifice anything to make [the] country stronger.” Going further, he described the claim of individual benefits as “a shame for many of us,” as he was educated to “attribute personal achievement to the great Party.”[43] This model continued for several years, and in that time, China advanced rapidly. In 1949, China had fewer than 40 scientific research institutes and less than 50,000 technological professionals. In 1965, however, these numbers grew to nearly 2.5 million scientists and technological professionals, as well as 1,714 research institutes.[44]

In this time, the Communist Party did develop foundational intellectual property right laws. Within a few short months of establishing themselves as a country, the Communist Party of China passed the “Provisional Regulations on the Protection of Patent Rights.”[45] This policy, however, was riddled with contradictions and loopholes. For example, patent rights could only be granted if the inventor was part of a larger, often state sponsored, organization, such as a research institute, factory or minefield. Additionally, Article 14 stated that should the state deem it necessary, all patent rights would be appropriated from the individual to the state.[46] Further, while Article 7 described a penalty for misuse of a patent without the patentholder’s consent, there was no process for calculating compensation, nor was any government body designated with enforcement measures.[47] These provisions, in essence, lived only on paper and failed to reach any point of practicality.

At the same time, the Chinese central government passed the “Provisional Regulations on Trademark Registration,” identifying trademarks as the primary means for a private enterprise to distinguish their goods.[48] Originally placed under the Central Administration for Private Enterprises (CAPE), this agency soon merged with the Central Administration for Foreign Enterprises (CAFÉ) to create the Central Administration of Industry and Commerce (CAIC).[49] This agency had a prominent role in the central government at first, highlighting a promising start for both private industry and trademark policy.

By 1953, however, the Community Party under Mao initiated its “great socialist transformation,” assuming control over all private industry in the state by 1956. In accordance to Mao’s first five-year plan, China assumed control over private enterprises to channel scarce resources into key industries, rapidly industrializing the nation.[50] As state-owned businesses now only had to produce goods to meet government quotas, rather than consumer demand, the need for trademarks quickly collapsed. When supplies ran short, which was often, typical consumers could not choose between brands of commodities, taking what they could to support themselves and their families.[51] Internal efforts for stronger intellectual property rights took a backseat to economic and industrial development, and as a result, the intellectual property right policies lost what little traction they once held.

From 1950 to 1966, intellectual property continued to lose face in China as a necessary backbone to state growth. The 1950 Trademark Regulations were replaced by the 1963 Trademark Regulations, which eliminated the right for trademark registrants to own a trademark.[52] Instead, trademarks were to be used to distinguish quality, similar to lei in the Qing Dynasty. Mirroring trademark regulations, the 1950 Patent Provisional Regulations were replaced in 1954, and then again in 1963, with each iteration stripping more and more rights from the patentholder.[53] The 1963 Inventions Regulations even went so far as to remove the term “patent,” replacing it with either “inventions” or “technological improvements.”[54] Driving this point home, Article 27 of the 1963 Regulations stated that, “all inventions are the property of the state, and no person or unit could claim monopoly over them.”[55] In a drive to direct all state growth, the Chinese government had made public nearly all claims of intellectual property.

Then, in the greatest blow to intellectual property rights, China underwent the infamous Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976. This sociopolitical movement vilified intellectuals, elites and government officials as capitalist cronies. The Central Administration of Industry and Commerce (CAIC) was forcibly dismantled, and its general director, Xu Dixin, was arrested and imprisoned for five years.[56] The 50,000 registered trademarks in China at the time were criticized as “representing capitalist values,” and fell into disuse.[57] Tens of thousands of leading scientists and technical professionals were lumped into a generalized “bourgeoisie,” sentenced to labor camps to pay for the social and financial capital that they had earned from their work.[58] Rewards for intellectual creation diametrically opposed socialist values, and for the following decade, intellectual property rights largely ceased to exist.

Rebuilding an Intellectual Property Rights Regime Post-Cultural Revolution

Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, and the concurrent end to the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Deng Xiaoping chose to alter the path of China’s growth. In the waning years of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party had begun to recognize the importance of structured intellectual property right laws. In 1973, a Chinese delegation was sent to attend a WIPO conference in Geneva, where Ren Jianxin, Director of Legal Affairs in the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, reported the importance of reestablishing China’s failed intellectual property rights system to then-Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.[59] The “Reform and Opening-Up” strategy, led by Deng, not only shifted a new importance towards foreign trade, but revitalized interest in intellectual property rights. In 1979, WIPO’s General Secretary, Arpad Bogsch, visited China, where he discussed how to implement a possible patent system, and the following year. In 1980, the People’s Republic of China joined WIPO and committed to a stronger intellectual property rights system by sending delegations across the world to learn about patent systems in other countries, including Germany, Brazil, and the United States.[60] In order to ensure China’s commitments and assist with the new system, General Secretary Bogsch visited Beijing nearly every year for the following twelve years, and was even awarded the title of “Honorary Professor” by Peking University.[61] Coming out of the Cultural Revolution, the international community recognized the potential market growth of China and desired a system that would protect their intellectual property.

Domestically, however, the development of patent policy was contentious. In 1978, China reinstated the 1963 Inventions Regulations with no regard for private ownership. Within a year, scientists and scholars recognized this shortfall, meeting to draft a revised policy that would allow for this ownership. As it was introduced, however, the policy faced sharp criticism from several agencies in the central government, including the Ministry of Machinery Industry, who argued that the monopoly of ownership over certain inventions would hinder state growth, not help it.[62] Delaying the policy for several years, the opposition finally agreed to allow the new policy, but only if it could adopt a series nearly 70 revisions, attempting to strip it of its power.[63] Following much debate, international criticism, and the 1982 Five-Year Plan that specifically desired strengthened patent policy, the Chinese government passed the 1984 Patent Law. Unlike its predecessors, the 1984 Patent Law was in-depth and exhaustive, making up 69 articles detailing everything from application procedures and review processes to enforcement measures.[64] Though far stronger than existing regulations, the new patent law still contained several deficiencies when compared to international standards. Unlike those of developed countries, patents could only be granted in China for fifteen years, compared to twenty in most other countries. Additionally, scientific discovery, pharmaceuticals, foods, beverages, disease treatments and anything derived from chemical processes could not be patented.[65] This later became a point of contention with the United States.

At about the same time, China’s trademark system underwent a massive reformation. In 1978, the central government reinstated the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC).[66] Prioritized with reconfiguring the country’s failed trademark registration system, the SAIC reunified the fractured, provincial-level trademark regime and put intellectual property at the forefront of China’s economic policy. As Chinese intellectual property expert Zhang Zhenqing highlights, the total number of trademarks in China following the Cultural Revolution was 32,500—a 40% decrease from pre-revolution numbers.[67] For reference, Japan had 107,042 trademarks at the time.[68] Even worse, 10,692 of these Chinese trademarks were “trademarks in confusion,” as the Cultural Revolution had allowed for identical trademarks to register in several provinces under different companies.[69] In order to revitalize Chinese private businesses and meet the new demands of an open economy, the SAIC pioneered Chinese intellectual property policy with the 1983 Trademark Law, which called for the protection of the exclusive rights of trademark holders.[70] This policy is often considered China’s “First Trademark Law,” and in the years following its promulgation, China joined the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property in 1985 and the Madrid Agreement for the International Registration of Trademarks in 1989. Though slow to start, the Communist Party of China was falling in line with the international intellectual property standards.

While the 1980’s reform was led by domestic pressure, where internal actors motivated stronger intellectual property policy, China in the 1990’s faced an influx of external forces. Deng Xiaoping had set the stage for explosive growth in China, helping the rest of the world realize the country’s profitable market. Foreign direct investment into China in the mid-1980’s stood around $4 billion, but had skyrocketed to approximately $35 billion by 1995, an increase of nearly ten-fold.[71] As more transnational corporations shifted focus to the newly emerged open economy, governments followed suit with a renewed push for stronger intellectual property laws.

Though foreign companies had previously complained of China’s weak intellectual property system, specifically as it related to patents, the US government did not get involved until 1988, when it revised its 1974 Trade Act and adopted the 1988 Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act.[72] Under these new policies, the US Trade Representative was tasked with investigating countries who operated under “unfair trade practices.”[73] Special 301, as the article was referred to, allowed the USTR to unilaterally issue sanctions against countries violating intellectual property rights. As a result, China and seven other countries were placed on a priority watchlist.[74] Though this designation carried no punitive action, it forced China to meet with the United States and draft a foundational Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). In doing so, however, the central government came under harsh domestic criticism for bowing to foreign powers.[75] Given that China had only escaped imperial control forty years prior, many Chinese people saw the intellectual property officials as selling out national interests and as a result, this hampered actual change from the Chinese intellectual property regime.

The Chinese government had to strike an even more challenging balance between foreign and domestic forces in 1991, when the US identified China as a priority foreign country. Under this designation, China had six months to improve its intellectual property rights system before facing $3.9 billion in trade sanctions.[76] This ignited a series of negotiations between the two countries, eventually ending in a signed MOU that, in December of 1992, translated into the Regulations on Administrative Protection of Pharmaceutical Products as well as the Regulations on Administrative Protection of Agricultural and Chemical Products.[77] Though they resolved several policy issues, the MOU (and the resulting regulations) failed to properly address enforcement and implementation.

Following these negotiations, China further developed its trademark policies as well. By promulgating the Anti-Unfair Competition Law in 1993, China continued to strengthen its trademark regime.[78] This, however, came without as much international pressure. When interviewed about why China advanced its trademark laws without international pressure, once SAIC official replied, “isn’t it a good opportunity to push ahead our own trademark legislations? Why should we wait until the other countries point their fingers at us? We should take the initiative by ourselves.”[79] Under a global magnifying glass, Chinese officials took progressive steps forward by seeking to improve internal regulations before punitive action.

These advancements, however, fell short of US expectations. Though the agency had not placed a strong emphasis on trademark infringements in the 1991-1992 trade negotiations, the USTR again labeled China on the priority list on June 30, 1994, singling out failed enforcements of copyright and trademark laws.[80] This initiated another several rounds of trade negotiations between the US and China[81], resulting in the Provisional Regulations on the Recognition and Management of Well-Known Trademarks in 1996.[82] This policy protected unregistered, well-known trademarks, offering some level of protection from infringement and counterfeiting similar to that of a registered trademark. Applying only to the United States at first, several other developed countries then pursued equivalent treatment, eventually pushing China to amend the 1996 Regulations in 1998, meeting the minimum expectations required by TRIPS and the Paris Convention.[83]

Finally, on December 11, 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization. After more revisions to its patent, trademark, copyright and trade secret policies, it was able to meet the necessary requirements of the global intellectual property community. By the time China joined the WTO, it had developed laws to protect geographical indicators, removed barriers for registering trademarks in China, and adopted language similar to TRIPS regarding the refusal of trademarks that could create confusion with well-known, unregistered trademarks. Additionally, they extended the period of dispute action from one to five years, allowing more time for trademark holders to identify violations and file legal action. Finally, local Administrations for Industry and Commerce (AIC), rather than just the criminal courts, could now order a violator to halt production of infringing goods, destroy existing products and impose a fine.[84] Altogether, this created an intellectual property atmosphere more hospitable for fair commerce, appeasing rightsholders both domestically and internationally.

Since joining the World Trade Organization, both China’s patent and trademark laws have undergone serious revisions. Prior to their acceptance to the international trading stage, most reforms to the Chinese intellectual property system had been propelled by outside, Western agencies. The US played a monumental role in the 1990’s, using a series of trade talks to force China to rapidly improve its protections and policies. Once it did so, however, the West receded from the conversation, opening space for China to independently review its polies in the context of desires held by domestic constituents. In this time, individuals reportedly felt it was unfair that the United States had forced China to develop strong intellectual property laws that, in many ways, inhibited domestic economic growth. As one official argued, the United States “copied Europeans for more than one century; why can’t [China] copy the Americans for twenty years? […] Did they follow these standards when they were at our stage of economic development? The US practices double standards.”[85] The developed countries had, only decades earlier, subjected China to a century of imperialization, and the resulting sentiment still molded the perspectives of many Chinese. As a result of voices like these, the political pendulum swung away from protecting foreign companies, appeasing domestic constituents and allowing for the increased infringements on foreign intellectual property. With accusations of violations growing exponentially, the United States in 2018 resumed its presence in the Chinese intellectual property realm through the US-China Trade War, leading to another series of revisions.

After a period of investigation, the central government concluded that although the new patent and trademark policies benefited Chinese business owners, many believed these benefits were only a byproduct of bowing to foreign powers. The real winners, they argued, were foreign companies that now had safeguarded access to Chinese markets. This belief led to a decade in which intellectual property policy focused on domestic constituents. In December of 2008, the central government passed a revised Chinese patent law, which among several changes, allowed for the compulsory licensing of monopolized patents when deemed necessary.[86] As a result, foreign enterprises had no voice on licensing terms should the Chinese government deem their product critical, illustrating that the pendulum had swung away from foreign influence to appease and appeal to domestic constituents.

Chinese trademark laws also saw several revisions post-acceptance to the WTO. For example, previous trademark legislations capped financial compensation for infringing trademarks at RMB 500,000 (~$60,000, using 2001 currency conversion rates).[87] Because of how profitable trademark violations quickly became, this limit on economic damages no longer served as an effective deterrent to violators. Additionally, the number of companies filing for trademark registration rapidly outpaced the capacity offered by the CNIPA Trademark Office.[88] At its minimum, registration for a trademark required twelve months to process paperwork, assuming it encountered no disputes, at which case this process could extend by another several months. The new process shaved this time down by approximately 25%.[89] In 2009, government officials petitioned to revisit China’s trademark laws, and five years later passed the new 2014 China Trademark Law.[90] This new legislation not only decreased the application timeline, but also increased the cap for financial compensation to RMB 3,000,000 (~$500,000, using 2014 currency conversion rates).[91] Though still far from the potential profits of a Chinese counterfeiting operation, this dramatic increase demonstrated a sharper focus on enforcement and deterrence. From a national policy perspective, China continued to improve its intellectual property regime, though placing a far larger focus on developing the internal economy rather than protecting foreign companies.

In 2018, the United States sought to shift this balance. After repeated allegations that China safeguarded and even promoted the theft of American intellectual property, President Trump initiated a series of tariffs against China. The US-China Trade War, as it would be named, leveraged tens of billions of dollars’ worth of goods to change China’s trajectory, forcing it to change what the US considered “unfair trade practices.”[92] Though controversial, some argue that these tariffs forced Chinese officials to finally take the enforcement of international intellectual property enforcement seriously. In an interview with the US Patent and Trade Office’s Senior Counsel for China Intellectual Property, he argued that for the first time in decades, Chinese intellectual property officials were finally ready to work with the United States.[93] Under the Obama administration, for example, the Chinese officials would come to the negotiating table and say one thing, but practice another. The US was allowing China to get away with violations under the rhetoric that China was slowly coming around to international expectations. As the US-China Trade War unfurled, though, these same Chinese officials were far more prepared to make concessions and negotiate future policies.[94] As a result, Chinese intellectual property rights saw another series of revisions.

In 2019, the Chinese National People’s Congress passed the 2019 Trademark Law, identifying bad-faith filings as illegal.[95] China, much like most of the international community, follows first-to-file registrations, meaning that regardless of who creates an idea or invention, the legal owner is whomever files the product first. Bad-faith filings occur when bad actors, with no relation to a trademark, file for ownership in a jurisdiction that the product does not currently exist in.[96] Further, the 2019 Trademark Law increased punitive damages to RMB 5,000,000 (~$700,000, using 2019 currency conversion rates), demonstrating that from a policy level, violations would not be tolerated.[97] Additionally, the government released amended patent examination guidelines, expediting the process for patent registration while affording more rights to the applicants.[98] Then in January 2020, the US-China Trade War took its first steps to a mutually agreed upon truce with the signing of the Phase One Trade Deal. Though discussing several facets of trade, over 40% of the trade deal outlined agreements on intellectual property, specifically detailing directives for enforcement. [99]

From Policy to Practice: How Trademark Counterfeiting Highlights Failed Enforcement Measures

As evidenced, China’s short history of development has placed an increasingly large emphasis on intellectual property rights, using national policy as the guidelines for safeguarding innovation and promoting growth. This section, however, aims to demonstrate how the realm of policymaking fails to reflect on local enforcement, where counterfeit manufacturing and patent theft still occurs. By giving a general overview of the claims against the People’s Republic of China, this section will craft the foundational argument that China has failed to enforce intellectual property rights on several accounts, allowing for the abuse of both domestic and foreign intellectual property.

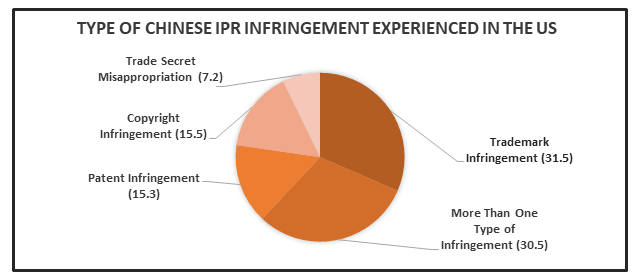

Trademark counterfeiting is the unauthorized, intentional use of another brand’s trademark to sell a similar, but often low-quality, product.[100] Though most often thought of as an issue only for companies, counterfeit products can negatively affect everything from local economies to a consumer’s health, even going as far as to fund other transnational criminal organizations and other crimes.[101] This section utilizes trademark counterfeiting as a lens to view Chinese intellectual property rights for two reasons. First, probable counterfeit goods are often easily identifiable on e-commerce sites, imitating the style of popular brands. Second, trademark violations capture nearly one third of all intellectual property infringements experienced by US firms, as highlighted by Figure 1.[102]

Due to its illicit and illegal nature, it is inherently challenging to understand the exact numbers behind counterfeit trade. Statistics based on product seizures, however, indicate that around 90% of all counterfeit products originate from China.[103] These estimates place the value of counterfeit goods coming from China at over $400 billion dollars.[104] This has not always been a major issue, however, as the illicit industry has grown by over 10,000% since 2000.[105] Though no metric is entirely reliable on its own, together, these statistics highlight how China’s counterfeiting enterprise has grown into an unparalleled giant in the past two decades.

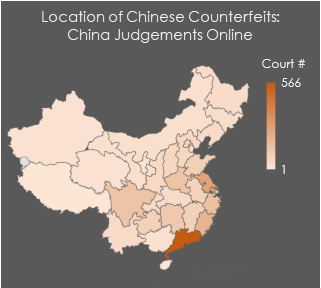

In understanding how China has become the global hub for counterfeit products, it is important to narrow down exactly where counterfeits in China are being produced. Using court data published online from China Judgements Online[106], the Chinese court database, Figure 2 highlights how the counterfeit manufacturing industry is not uniform across the country but instead, focused in specific regions and provinces. Though nearly every province prosecuted at least one case, the distribution skewed towards provinces along the coast, specifically those known to be high in manufacturing. Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Sichuan are all notable provinces, who together accounted for 49.6% of the total cases of trademark violations. Additionally, provinces containing Special Economic Zones (SEZs, similar in policy to Free Trade Zones) had far more instances of counterfeiting than provinces without this designation, indicating that a decreased presence of regulations, combined with an increased opportunity for trade, amounted in greater opportunity for counterfeit goods.

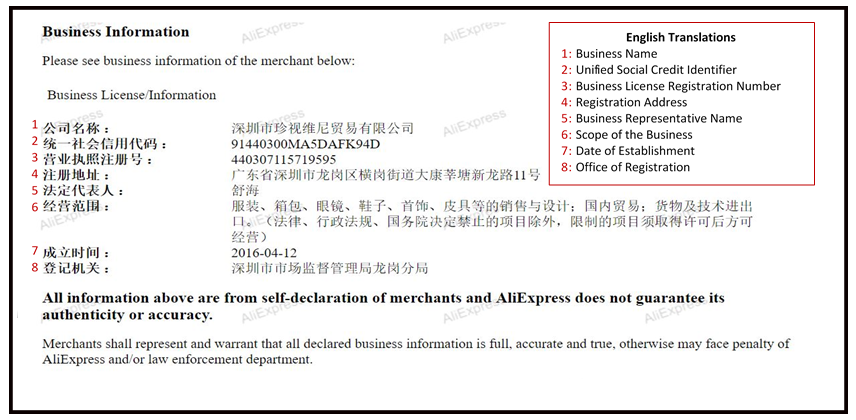

Not only does the Chinese judicial system know the regions in which counterfeiting takes place, but law enforcement also has the capability to identify exactly where these businesses are located. For Chinese-facing third party e-commerce marketplaces, such as Taobao or JD.com, independent sellers are required to upload business licenses, including the registrant’s name, the business name and its address. Oftentimes, this information is available publicly, allowing for anyone to investigate the business. Figure 3 showcases a business license found for a distributing company, named, “Lowest Price Women Bag,” selling probable counterfeit handbags.[107] In an age where the Chinese government requires more information from its citizens than ever before[108], the process of identifying a business, its owners, and the operating location is genuinely simple.

The trade of counterfeit goods is massive in scope, value and size, yet the effort needed to dismantle it is often minimal. When businesses identify that their goods have fallen victim to counterfeiting in China, several barriers exist in reporting. Chinese law enforcement seldom investigates intellectual property rights claims seriously, meaning that in many cases, successful businesses will initiate their own private investigations by employing Chinese partners to gather evidence.[109] Then as they gather sufficient evidences, the businesses will present it to local law enforcement. Even with enough evidence gathered, however, these cases often will not receive the attention they deserve. In one instance, Alibaba reported that of the 1,910 cases of suspected counterfeiting that it had referred on to police, only 129 people were found guilty, highlighting the dire need for effective law enforcement.[110]

Understanding the Chinese Actors: Politicians, Public Servants and the People

The enforcement of intellectual property rights in China highlights a division that many individuals fail to understand. Though Western states often describe the country in a negative view, highlighting an authoritarian regime supplied by a population homogenous in thought,[111] views of intellectual property rights throughout the country highlight the division in thought between three key political bodies: high-ranking members of the Chinese Communist Party, local party officials located throughout the country, and the people. Each of these groups experiences different driving factors, and as such, the enforcement and interpretation of intellectual property right laws varies between each group. The purpose of this section is to explore how each group of people views intellectual property, highlighting some of the contributing factors to China’s failing enforcement measures.

The Communist Party from a National Perspective: How Intellectual Property Shapes Economies

The Communist Party of China faces a conundrum that few, if any, other states encounter in their economic decision-making process. While it is true that the promotion of intellectual property rights generally improves and strengthens a growing economy, the People’s Republic of China has become a massive exporter of counterfeit goods, whose manufacturing and distribution sustains a large part of the Chinese GDP. Party members face the unique challenge of balancing long-term and short-term economic strength, for in the case intellectual property laws in China, one must come at the expense of the other.

Before diving into the complexities of enforcing intellectual property rights, this paper will first outline the primary goals of the Communist Party of China. In 2008, Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo stated that the three primary concerns of the People’s Republic of China are maintaining regime stability, maintaining territorial sovereignty, and continued economic growth.[112] China needs to maintain a high GDP growth rate, generally between 6% and 6.5%, in order to ensure employment for its population.[113] By utilizing a balance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and market mechanisms to target this range each quarter, the government can plan its economy, keeping people employed and ensuring regime approval. When this number faulters, fears arise that a slowed economy will decrease citizen approval for the government, creating the potential for instability.[114] As a result, economic growth is key to the Communist Party.

Though intellectual property right laws protect and promote innovation, they also halt the counterfeit manufacturing industry. If China exports counterfeit goods valued at approximately $400 billion,[115] and China has a total export value of $2.4 trillion,[116] one can see that illicit goods contribute significantly to the country’s trade economy. The Communist Party, when determining intellectual property rights law, has to balance the potential for long-term growth promoted by intellectual property rights with the reality of short-term losses that strict enforcement would instigate.[117] This creates an apparent contradiction when working with foreign entities that want stricter laws, such as the United States. Though the US pressures China into stronger intellectual property enforcement, the Chinese government cannot allow for its economy to suffer, especially to appease outside actors.

It is important to note, however, that this does not mean that the Chinese government has not taken any steps to enforce intellectual property rights. Pioneered in 2014, the National People’s Congress identified a growing need for judiciary bodies focused specifically on intellectual property rights cases. A mountain of claims highlighted how local and regional judicial systems had little training in intellectual property, and therefore, would often disregard such cases.[118] As a result, the government created specialized intellectual property courts in Shanghai, Guangzhou and Beijing.[119] This system gained national attention for its incredible work and has since grown to over 20 specialized courts and tribunals, including even an appellate IP court.[120] The judges of these courts are generally considered to be some of the best in China, with at least a decade of experience in intellectual property right law.[121] This has played a significant role in the annual number of court cases relating to violations of intellectual property in China, as highlighted by Figure 4.[122] Both 2018 and 2019 experienced similar numbers, though this is largely due to claims that the specialized IP courts had reached their capacity for legal cases.[123]

The Communist Party at a Local Level: Political Meritocracy and Protectionism

Though the Chinese government follows central ideologies that guide its growth and development, how these policies are interpreted and implemented from a local level sometimes differs from that of their national counterparts. Intellectual property rights law is one example of this. While the national government has to balance long-term and short-term economic growth, provincial and municipal governments are constantly pressed to outperform not only each other, but their previous numbers. This section of the paper will focus on how the interests of certain local governments oppose the intended goals of intellectual property enforcement.

Before discussing intellectual property rights, one must understand how the Chinese government and its levels of political meritocracy work. The Communist Party of China does not operate in a democratic fashion that the United States is accustomed too. Instead, it utilizes a hierarchical electoral system, where local officials are directly elected.[124] Then, as they achieve success and better their community, they are given the opportunity to rise into higher positions with more responsibility. This process of political meritocracy combines personal aspirations with benevolent altruism to motivate officials to success.[125] At the same time, however, it creates ample opportunity for corruption and faked economic figures.

Historically, China is not unaccustomed to faked economic data. From 1959 to 1961, China underwent the Great Leap Forward, in which the country’s grain output fell dramatically as the country aimed to mass industrialize. Under the impression that collectivization would increase productivity, the central government set unreasonable grain production goals for each locality, arguing that an increase in efficiency would allow for a shift to industry. Knowing that their political futures relied on meeting certain targets, local officials distorted and exaggerated their statistics of grain production, over-reporting their numbers to appear successful.[126] As a result, the country plunged into a famine that killed tens of millions of people. Since then, critics have continued to accuse China of falsifying numbers relating to everything from economic data[127] to COVID-19 deaths[128], all with varying degrees of accuracy.

In the present, Chinese officials still feel an immense pressure to perform well. Not only do their political futures rely on this through a system of political meritocracy, but their personal finances do as well. The civil service pay for Chinese officials is largely determined by the success of the province they are managing. As localities perform better, the officials are essentially awarded through a system of state profit-sharing.[129] Together, these two factors create an environment hospitable for continued counterfeiting practices. If a province’s wealth is strongly connected to its manufacturing industry, and that industry partakes heavily in counterfeit goods, then there is a direct disincentive to enforce intellectual property right laws. Not only would it affect their regional indicators for success, such as employment or GDP per capita, but it could have a direct affect on their personal salaries. However, many foreign companies have found success in rewarding Chinese local officials for arresting counterfeiters.[130] By attaching some level of social significance and public recognition to anti-counterfeiting measures, they outweigh the motivations for allowing violations of intellectual property to continue.

Intellectual property laws serve two purposes, protecting creativity and innovation while also promoting it. Though the enforcement aspect of intellectual property protections runs against the personal motivations of local officials, the promotion of innovation is highly beneficial to a region’s success. Local officials would benefit from promoting intellectual property through registrations and applications rather than enforcement. This is largely evidenced by the fact that China process the most applications for intellectual property in the world,[131] yet does not even rank in the top ten for most innovative countries.[132] They only need to register numbers, so that they can outperform and outcompete other regions. Local officials push for quantity over quality in order to boost their numbers, protecting their image while preserving their state economies.[133]

Overall, local officials face a very different decision-making process from their national counterparts. While both value the economic and creative development of the regions they’re responsible for, each group faces different motivations and external pressures. As such, it is important to identify these relationships and driving forces when responding to the issue of intellectual property rights in China. Policy exists, yet the enforcement measures have yet to take a real effect.

The People: Those Who Counterfeit, and Those Who Don’t

The final major domestic actor in intellectual property in China is the people, including those that violate intellectual property and those that do not. It is important to state that at its core, counterfeiting and other violations of intellectual property rights are crimes pursued for monetary gain. The counterfeiting enterprise has been viewed as more profitable than the drug trade,[134] and even more enticing, it is a low-risk crime to perform.[135] Not only can the products be challenging to identify, but the enforcement is low. Should an individual be caught and tried, the punitive damages are often dwarfed by the profits earned from the crime. These profits can be realized anywhere in the world, though, as they are not tied down by a specific location. Yet, nearly all counterfeit manufacturing happens in China. The purpose of this section is to discuss some of the cultural characteristics of China that make it hospitable for violations of intellectual property rights. Further, it is to highlight how culture, ideology, and state history can affect the implicit perceptions of intellectual property rights, not necessarily providing a scapegoat for why counterfeiters counterfeit, but illustrating the higher degree of tolerance that Chinese society has for it.

First, China is a collectivist culture in a socialist country built on a foundation of Confucianism and Taoism, and as such, the very notion of intellectual property rights runs contrary to implicit beliefs. Collectivist cultures generally value the needs of a group over the needs of an individual, and in the realm of intellectual property, that is most often reflected by the perception of a creative work’s purpose.[136] Intellectual property rights are an inherently individualized concept, highlighting the need for an individual’s ownership of an idea over the possibility that the group could build upon, improve and altogether benefit from, the work. Going further, China was built on the ideals of Confucianism and Taoism.[137] Confucianism emphasizes the role of the public domain, building on previous works to not only meet an individual’s needs, but to share with others to improve the general welfare. As Confucius declares in the Analects, “He who by reanimating the Old can gain knowledge of the New is fit to be a teacher.”[138] By this logic, creative works belong to the public, who has the responsibility to interpret and re-interpret it as they see fit.[139] This notion of public ownership translates into more recent history through the piece Kong Yi Ji, a famous work published in 1919 by Chinese author Lu Xun. It is Lu Xun that coined the phrase, “To steal a book is an elegant offense,”[140] highlighting the notion that literature, and subsequently innovation, should be free for all peoples. It is not a crime to be looked down upon. From another perspective, Taoism preaches the principles of simplicity and letting go. By removing one’s self from personal possessions and material desires, the barriers to happiness and good health fall away too.[141] Removing the desire for personal property, again, runs opposite to the notion of intellectual property rights. Just as many American tout how Christianity has shaped and influenced the United States, the argument stands that Confucian and Taoist values, the foundation for Chinese society,[142] can shape the implicit views of intellectual property rights in China.

Finally, there exists a paradigm that the United States must be aware of as it pushes China to adapt to international intellectual property right laws. Though the country has grown rapidly, it is still young, and by many metrics, the People’s Republic of China still considers itself a developing country.[152] Recognizing this, many Chinese citizens point out that when the United States was at this point in its development, American businesses were rampantly violating Britain’s intellectual property rights. A prime example includes Charles Dickens, who in 1842 visited the United States only to find his works pirated and shared throughout the country.[153] Other developed countries also shared in a history of intellectual property theft, including Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.[154] Combined with the fairly recent “Century of Humiliation” that still haunts many in China, the idea of a Western country enforcing hypocritical laws on China has shaped how many view the global intellectual property system. No matter that the scope of the problem is larger than ever before, the perception exists that the United States is unfairly persecuting China for violations when it had, at one point, used these very same tactics to develop their own businesses.

China is founded on a culture different than that of the West, and as such, there are certain things that are viewed differently. Intellectual property rights, and the ownership of intangible goods, is one example. Though monetary gain is the primary motive for counterfeiting products, Confucian and Taoist principles have likely influenced how the Chinese society views this industry. Furthermore, shanzhai-ism and the unique role that the West has had with China augments that perception, providing even more of negative perception towards the western intellectual property standards. As Dr. Gregory Mandel, Dean of the Tsinghua University of Law in Beijing, once highlighted, the role of public perception towards intellectual property rights affects how it is enforced and understood. Misperceptions around it limit its legitimacy and function, meaning that if there is to be a functionally successful system of intellectual property rights, it needs to include the education of the public.[155]

Zooming Out: Understanding Intellectual Property through International Relations Theory

Though domestic in nature, the role of intellectual property rights has become increasingly international as the world has grown more globalized. The World Trade Organization, World Intellectual Property Organization and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development are all examples of international institutions that have dedicated at least part of their mission to the enforcement of intellectual property rights. The question that derives from this, however, is whether or not these international institutions work at enforcing and safeguarding these laws. The purpose of this section is to use liberal international relations theory to analyze the role of international institutions in intellectual property, arguing that they have promoted global standards to hold China accountable.

To begin, liberalist international relations theory primarily includes three principles. First, the rejection of the notion that international relations will only result in power politics. Second, that international cooperation can bring about mutual benefits. Finally, international organizations and nongovernmental actors can bring about change in a state.[156] While a realist may argue that China and the United States are destined for conflict, a liberalist would counter with evidence that international organizations can promote peace by providing other economic and diplomatic means.

In the case of Chinese intellectual property right law, international institutions were not necessary to their initial development, but beneficial to their growth. As highlighted in this research, the Chinese government sought to establish these laws within the first few years of the PRC’s existence. Though they were not effectively enforced, this was more due to the country’s relative youth, being only a few years old. Following the cultural revolution, the state once again sought to reestablish this foundational policy, knowing that intellectual property right laws promote sustainable growth. This time, though, they had assistance and support from WIPO, who shared knowledge on successful systems. As the Communist Party was finally welcomed by the international community, the world then saw the United States play an active role in building a stronger intellectual property regime in China. Some argue, however, that this was only a byproduct of the country attempting to gain access to Chinese markets. As the country failed to implement policies suitable to the United States, they underwent trade talks, eventually concluding with appropriate and agreeable policy. WIPO and, later, the WTO both played significant roles in the development, monitoring of, and enforcement of intellectual property standards in China. Though they have no direct control over the Chinese state or its people, it has successfully initiated discussion and provided framework for pushing China to continue to develop this aspect of global law.[157]

Though China had initial desires for developing an intellectual property regime, it was the international community that fostered its growth and held the national government accountable for instituting relevant policy. The incentive of joining the WTO greatly influenced how China revised and amended its policies, providing standards for stricter intellectual property rights system for both domestic and foreign actors. From a realist perspective, the development of these laws in China would have come with threats of conflict and retaliation, yet, these were largely avoided as a result of international institutions and multilateral trade agreements.

Conclusion

The People’s Republic of China, in less than half a century, has created an intellectual property system allowing it to maintain global operations. China has demonstrated a continued interest in its intellectual property system, revising policies at least once a decade, their enforcement falls short of international expectations China has become the global hub for counterfeit products, and numerous allegations exist of Chinese companies stealing technology from US firms. While frustrating for US policymakers and brand owners, understanding the problem from a perspective of actor analysis can provide greater insight into what motivates effective enforcement. While national officials need to balance long-term and short-term economic stability, local officials seek consistent economic success and measured development—facets of a region that intellectual property enforcement could hamper. Finally, the perspective of the Chinese population provides greater insight into the general tolerance for counterfeit products.

Intellectual property rights focus on intangible assets, providing worth to creativity and innovation. Though China has taken measured steps to develop its policies, it is far from a perfect system. By continuing to utilize international institutions and economic statecraft, however, the international community can continue to hold China accountable for protecting intellectual property. These tactics, however, need to be supplemented by relationship building, public education and mutual understanding. Only with these key aspects will China’s perspective on intellectual property change, moving to one where companies both foreign and domestic can operate without the fear of theft or imitation.

Endnotes:

[1] Rosenbaum, E. (2019, March 1). 1 in 5 corporations say China has stolen their IP within the last year: CNBC CFO survey. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/28/1-in-5-companies-say-china-stole-their-ip-within-the-last-year-cnbc.html

[2] OECD, & European Union Intellectual Property Office. (2019). Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Value, Scope and Trends. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9f533-en

[3] OECD. (2019, March 18). Trade in fake goods is now 3.3% of world trade and rising. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/trade-in-fake-goods-is-now-33-of-world-trade-and-rising.htm

[4] World Intellectual Property Organization. (n.d.). What is Intellectual Property. 450(E), 25.

[5] WIPO. (n.d.). Patents. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/patents/en/index.html

[6] WIPO. (n.d.). Trademarks. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/trademarks/en/

[7] WIPO. (n.d.). Copyright. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/copyright/en/

[8] WIPO. (n.d.). Trade Secret. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/sme/en/ip_business/trade_secrets/trade_secrets.htm

[9] Park, W. G., & Lippoldt, D. (2008). Technology Transfer and the Economic Implications of the Strengthening of Intellectual Property Rights in Developing Countries. OECD Trade Policy Working Papers, 62.

[10] World Intellectual Property Indicators 2019. (2019). World Intellectual Property Organization. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5982599

[11] Phillips TIM: Knockoff: The Deadly Trade in Counterfeit Goods: the True Story of the World’s Fastest Growing Crime Wave. London: Kogan Page; 2005.

[12] The Illicit Trafficking of Counterfeit Goods and Transnational Organized Crime. (n.d.). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.unodc.org/documents/counterfeit/FocusSheet/Counterfeit_focussheet_EN_HIRES.pdf

[13] The Illicit Trafficking of Counterfeit Goods and Transnational Organized Crime (n.d.). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.unodc.org/documents/counterfeit/FocusSheet/Counterfeit_focussheet_EN_HIRES.pdf

[14] China “fake milk” scandal deepens. (2004, April 22). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/3648583.stm

[15] Ahlers, M. (2012, October 10). Feds warn of counterfeit airbags being installed as replacements. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2012/10/10/us/counterfeit-airbags/index.html

[16] Counterfeit Respirators / Misrepresentation of NIOSH-Approval | NPPTL | NIOSH | CDC (2020, April 21). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/usernotices/counterfeitResp.html

[17] Thompson Jr., W. C. (2004). Bootleg Billions: The Impact of the Counterfeit Goods Trade on New York City. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/bootleg-billions-the-impact-of-the-counterfeit-goods-trade-on-new-york-city/

[18] Freeman, G., Sidhu, N., & Montoya, M. (n.d.). A False Bargain: The Los Angeles County Economic Consequences of Counterfeit Products. Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.wired.com/images_blogs/threatlevel/files/2007_piracy-study.pdf

[19] OECD. (2019, March 18). Trade in fake goods is now 3.3% of world trade and rising. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/trade-in-fake-goods-is-now-33-of-world-trade-and-rising.htm

[20] Counterfeit Goods: Easy Cash for Criminals and Terrorists, 109th Cong. (2005) (testimony of Senator Susan Collins)

[21] WIPO. (n.d.). Trademarks. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/trademarks/en/

[22] Shao, K. (2005) Look At My Sign! Trademarks in China from Antiquity to the Early Modern Times. The Journal of the Patent and Trademark Office Society, 87 . pp. 654-682.

[23] Eckhardt, G. M., & Bengtsson, A. (2010). A Brief History of Branding in China. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146709352219

[24] Eckhardt, G. M., & Bengtsson, A. (2010). A Brief History of Branding in China. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146709352219

[25] Language Families | About World Languages. (n.d.). MustGo.Com. Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/language-families/

[26] Wang, J., & Sunihan, S. (2014). An Analysis of Untranslatability between English and Chinese from Intercultural Perspective. English Language Teaching, 7(4), p119. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n4p119

[27] Keller, Kevin. (2008). Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring and Managing Brand Equity. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

[28] Eckhardt, G. M., & Bengtsson, A. (2010). A Brief History of Branding in China. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146709352219

[29] Hamilton, G., & Lai, C. K. (1989). Consumerism Without Capitalism: Consumption and Brand Names in Late Imperial China. In H. Rutz & B. Orlove (Eds.), The Social Economy of Consumption (pp. 253-279). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

[30] Ma, Dongqi. 2007. Chinese trademark and culture (English Translation). Beijing: Chinese Literature Press.

[31] Li, S. (2018, November 10). Time-honored Beijing Tong Ren Tang Showcasing Its Attributes Overseas. China Today. http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/ctenglish/2018/et/201810/t20181011_800143842.html

[32] Beijing’s Oldest Restaurants. (2012, November). Beijing Tourism. http://english.visitbeijing.com.cn/a1/a-X9YI0G4867B46C0064323D

[33] Hamilton, G., & Lai, C. K. (1989). Consumerism Without Capitalism: Consumption and Brand Names in Late Imperial China. In H. Rutz & B. Orlove (Eds.), The Social Economy of Consumption (pp. 253-279). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

[34] Hamilton, G., & Lai, C. K. (1989). Consumerism Without Capitalism: Consumption and Brand Names in Late Imperial China. In H. Rutz & B. Orlove (Eds.), The Social Economy of Consumption (pp. 253-279). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

[35] Yang, Boda. (1987). Qingdai Guandong Gongpin: Tributes from Guangdong to the Qing Court. Hong Kong: Art Museum, City University of Hong Kong.

[36] Wang, Yifan. 2007. Brand in China. Beijing: Wuzhou Communication Press

[37] Heuser, Robert. (1975). The Chinese Trademark Law of 1904: A Preliminary Study in Extraterritoriality, Competition and Late Ch’ing Law Reform. Oriens Extremus 22(2): 183-210.

[38] 名牌(知名品牌)_百度百科. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2020, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%90%8D%E7%89%8C/423794

[39] 名牌(知名品牌)_百度百科. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2020, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%90%8D%E7%89%8C/423794

[40] Zi, E. L. (2006, December 12). 中国名牌VS驰名商标. Sina. http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4164958f0100068c.html

[41] Eckhardt, G. M., & Bengtsson, A. (2010). A Brief History of Branding in China. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146709352219

[42] Why Did the Communists Win the Chinese Revolution. (2016). Constitutional Rights Foundation, 4.

[43] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[44] Chen, J. (1994). 当代中国科学技术发展. Hubei Education Press.

[45] Provisional Regulations of Aug. 28, 1950, Concerning the Registrations of Trademarks, 1 FLHB 528.

[46] Provisional Regulations of Aug. 17, 1950, Concerning the Protection of the Invention Right and Patent Right, 1 FLHB 359

[47] Provisional Regulations of Aug. 17, 1950, Concerning the Protection of the Invention Right and Patent Right, 1 FLHB 359

[48] Provisional Regulations of Aug. 28, 1950, Concerning the Registrations of Trademarks, 1 FLHB 528.

[49] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[50] McKnight, B., & Franke, H. (2020). China—The transition to socialism, 1953–57. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. https://www.britannica.com/place/China

[51] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[52] Provisional Regulations of Apr. 10, 1963, Regulations on Awards for Inventions and Technical Improvements.

[53] Guan, W. (2014). Intellectual Property Theory and Practice: A Critical Examination of China’s TRIPS Compliance and Beyond. Springer.

[54] Provisional Regulations of Nov. 3, 1963, Regulations on Awards for Inventions and Technical Improvements.

[55] Art. 27, Provisional Regulations of Nov. 3, 1963, Regulations on Awards for Inventions and Technical Improvements.

[56] Fang, Z. (2002). 回忆许涤新. Haitian Press.

[57] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[58] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[59] 25 Years of Intellectual Property Protection. (2013, July 17). CNIPA. http://english.sipo.gov.cn/news/iprspecial/919158.htm

[60] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[61] Organization, W. I. P., & Bogsch, A. (1992). The First Twenty Five Years of the World Intellectual Property Organization (1967-1992). WIPO.

[62] 赵元果. 2003.中 国专利制度的孕育与诞生. 北京:知识产权出版社.

[63] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[64] Patent Law of Mar. 12, 1984, Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China.

[65] Patent Law of Mar. 12, 1984, Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China.

[66] Trademark Office of The State Administration. (n.d.). Retrieved April 27, 2020, from http://sbj.cnipa.gov.cn/sbjEnglish/

[67] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[68] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[69] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[70] Zhang, L. (2013, September 13). China: Trademark Law Revised | Global Legal Monitor [Web page]. //www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/china-trademark-law-revised/

[71] Lemoine, F. (2000). FDI and the Opening UP of China’s Economy. Centre D’etudes Prospectives Et D’Inforformations Internationales.

[72] H.R.4848 – 100th Congress (1987-1988): Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/4848

[73] H.R.4848 – 100th Congress (1987-1988): Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/4848

[74] Fact Sheet: “Special 301” on Intellectual Property. (1989). United States Trade Representative. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/1989%20Special%20301%20Report.pdf

[75] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[76] Economy, E. (2019). Trade: Parade of Broken Promises. Democracy Journal, 52. https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/52/trade-parade-of-broken-promises/

[77] MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ON THE PROTECTION OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY. (1992). Trade Compliance Center. https://tcc.export.gov/Trade_Agreements/All_Trade_Agreements/exp_005362.asp

[78] Law Against Unfair Competition of the People’s Republic of China. (1993). People’s Republic of China. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/cn/cn011en.pdf

[79] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[80] USTR ANNOUNCES THREE DECISIONS: TITLE VII, JAPAN SUPERCOMPUTER REVIEW, SPECIAL 301. (1994). United States Trade Representative. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/1994%20Special%20301%20Report.pdf

[81] U.S.-China Trade: Implementation of Agreements on Market Access and Intellectual Property. (1995). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/230/220848.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

[82] Bird, R., Bird, R., & Jain, S. C. (2009). The Global Challenge of Intellectual Property Rights. Edward Elgar Publishing.

[83] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[84] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[85] Zhang, Z. (2019). Intellectual Property Rights in China. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[86] Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China (2008). (n.d.). CCPIT PATENT AND TRADEMARK LAW OFFICE. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.ccpit-patent.com.cn/node/1068/1064

[87] The Trademark Law of The People’s Republic of China. (1993, February 22). Consulate-General of the People’s Republic of China in San Fransisco. http://www.chinaconsulatesf.org/eng/kj/wjfg/t43946.htm

[88] World Intellectual Property Indicators 2017 Trademarks. (2017). World Intellectual Property Organization. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2017-chapter3.pdf

[89] Gerben, J. (n.d.). Average Time-frame for Trademark Proceedings in China. Gerben Intellectual Property. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.gerbenlaw.com/blog/average-time-frame-for-trademark-proceedings-in-china/

[90] Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China. (2013). World Intellectual Property Office, 24.

[91] Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China. (2013). World Intellectual Property Office, 24.

[92] President Donald J. Trump is Confronting China’s Unfair Trade Policies. (n.d.). The White House. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-confronting-chinas-unfair-trade-policies/

[93] Longo, J. (2020, March 30). Phone Interview with M. Mangelson, USPTO Senior Counsel for China IP Policy [Phone].

[94] Longo, J. (2020, March 30). Phone Interview with M. Mangelson, USPTO Senior Counsel for China IP Policy [Phone].

[95] Zhang, L. (2019, July 30). China: Trademark Law Revised, Prohibiting Bad-Faith Trademark Filings | Global Legal Monitor [Web page]. //www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/china-trademark-law-revised-prohibiting-bad-faith-trademark-filings/

[96] Bin, Z., & Lei, F. (n.d.). Trademarks: In bad faith. World IP Review. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.worldipreview.com/contributed-article/trademarks-in-bad-faith

[97] Zhang, Z. (2019, November 19). China’s New Trademark Law in Effect from November 1, 2019. China Briefing News. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-new-trademark-law-effect-november-1-2019/

[98] New China Patent Examination Guidelines Effective November 1, 2019. (n.d.). The National Law Review. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.natlawreview.com/article/new-china-patent-examination-guidelines-effective-november-1-2019

[99] Lighthizer, R., & Mnuchin, S. T. (2020). ECONOMIC AND TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA. http://prod-upp-image-read.ft.com/d08f2b80-37b2-11ea-a6d3-9a26f8c3cba4

[100] WIPO. (n.d.). Trademarks. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.wipo.int/trademarks/en/