Jeremy Wilson and Jay Kennedy, 2015

Introduction

In July 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted FedEx for allegedly facilitating the shipment of controlled substances from illegal internet pharmacies to American consumers (U.S. DOJ, 2014). This is not the first time the U.S. Government has brought legal action against a major shipping company for transporting illegal goods within the U.S., as UPS faced a similar indictment in 2013 (U.S. FDA, 2013). While UPS ultimately settled its case, FedEx denies wrongdoing and has vowed to fight the charges (Stevens, 2014). While it is not clear whether FedEx was involved in transporting counterfeit goods, the indictment alleges that FedEx was aware of the illegal nature of some of its customers’ business practices. The U.S. Government further alleges that knowledge of these illegal practices did not stop FedEx from providing shipping, storage, and packaging services to illegal internet pharmacies, but rather led it to implement strategies aimed at mitigating the financial risk associated with maintaining relationships with these customers.

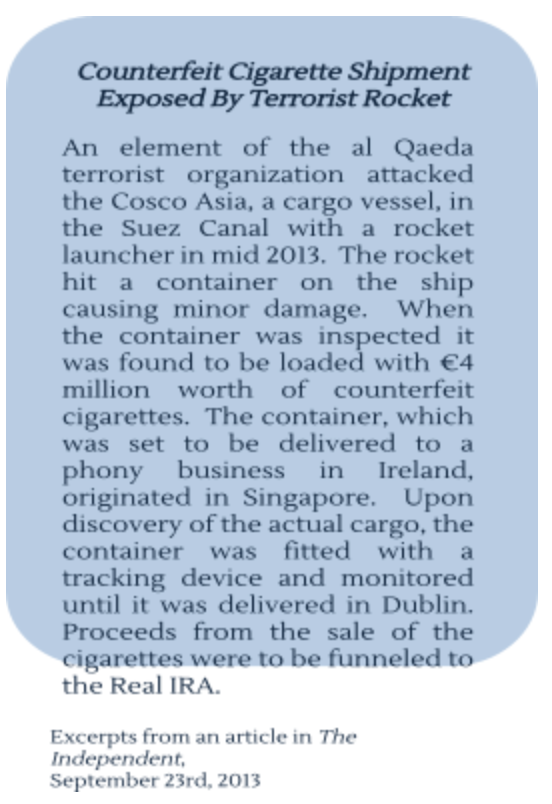

The indictment of FedEx, a major transportation intermediary that services customers in over 220 countries and handles more than 11 million shipments daily (FedEx, 2015), raises several questions about the role legitimate shipping companies play in illegal activities occurring throughout the world. These questions go beyond the role of express-package shippers such as FedEx and UPS. Indeed, while express-mail services account for 21 percent of the value all seizures by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials in 2013, seized cargo containers from ocean-going vessels accounted for 63 percent. The market value (as determined by manufacturers’ suggested retail price for legitimate goods) of counterfeit goods seized from ocean-going cargo containers was $1.1 billion. Similarly, 81 percent of European customs seizures of counterfeit items arrive via ocean-going cargo containers. A recent operation conducted by the European Anti-Fraud Office seized counterfeit goods and cigarettes from ocean-going cargo vessels valued at more than $82 million; these goods would have generated about $26 million in tax revenue and duties (World Intellectual Property Review, 2014).

Efforts to address all aspects of counterfeiting must include clear definition and understanding of intermediaries’ responsibilities (Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting And Piracy, or BASCAP, 2015). To help achieve such understanding, this paper discusses the roles of ocean transportation intermediaries (non-vessel operating common carriers and freight forwarders) and ocean-going cargo shipping vessel operators. We also discuss the general duties these intermediaries have to stop the proliferation of counterfeit goods by enacting Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures and engaging with brand owners.

Legitimate Intermediaries and Counterfeit Trade

Counterfeit goods are shipped throughout the world via many of the same legitimate distribution channels used by brand owners. Like shippers of legitimate goods, shippers of counterfeit goods consider the amount of goods being shipped, the origination and destination of the counterfeit items, and whether the illicit goods are being shipped directly to consumers or to a distribution hub when making their shipping choices. Not surprisingly, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection express-mail services are the most common mode used to ship smaller quantities of counterfeit goods into the United States (2013), while ocean-going cargo containers are used to ship large quantities of goods to a single distribution point for counterfeit products.

Because counterfeit goods move along the same channels as legitimate goods, parcel delivery and cargo container companies are routinely employed as unwitting, or negligent, partners in the movement of counterfeit goods around the world. These intermediaries may be liable for their role in moving counterfeit goods (BASCAP, 2015).

Role of Ocean Transportation Intermediaries (OTIs) in Counterfeit Trade

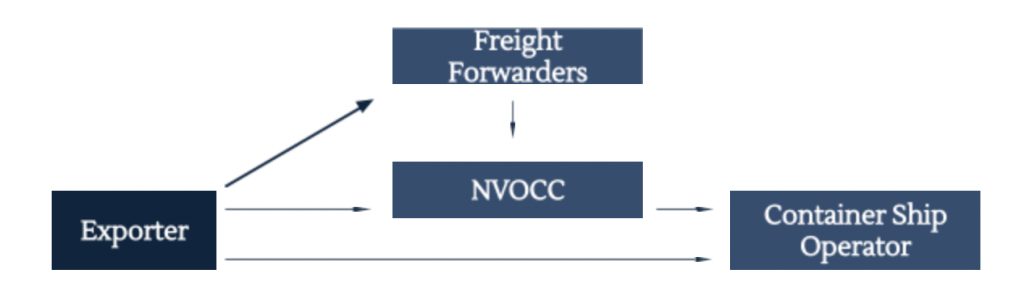

Many specific legitimate shipping procedures can also help obscure or conceal the parties with which such shipments originate, or the goods that are being shipped. Parties (including product counterfeiters) seeking to ship products by ocean-going container ship have several options available to them (Figure 1). They can contract directly with a vessel operator to ship their cargo as needed. Such shipments, however, shipments typically need to be full-container load (FCL) shipments that are transported under a single bill of lading as containing only one consignee’s goods.

Shippers who do not ship full containers may choose less-than-container-load, or LCL, shipments. Shippers seeking LCL shipments have two options: working with a freight forwarder who contracts with a non-vessel operating common carrier (NVOCC), or working with an NVOCC that handles freight forwarding as well. Freight forwarders typically do not own shipping vessels or shipping containers. Rather, they work with customers to identify the most efficient and cost-effective method to move cargo from one location to another. They use their experience and knowledge to help customers navigate Customs paperwork and other relevant documentation requirements. Freight forwarders may contract with cargo carriers but do not directly move the cargo themselves. The relationships freight forwarders have with NVOCCs and shipping lines allows them to direct cargo to the most efficient intermediary.

NVOCCs do not own cargo container ships but rather work as consolidators of freight. Customers with LCL shipments may enlist an NVOCC to facilitate the shipment of their goods. NVOCCs will consolidate multiple individual LCL shipments into an FCL shipment transported under a single bill of lading containing only one consignee’s goods. Working with vessel operators, NVOCCs purchase space on container ships for these consolidated shipments. In some cases, the NVOCC is also the freight forwarder, handling multiple client-shipping needs. In other cases, the NVOCC receives freight from an independent freight forwarder and provides no other services to the primary customer but containerization.

Because NVOCCs consolidate freight from a multitude of customers, any single container may have many different types of goods from many different and unrelated customers. An NVOCC can ship a container under its own name if it is properly registered with the Federal Maritime Commission. In such cases, the NVOCC, and not the entities importing or exporting goods, becomes the shipper of record. This means the NVOCC assumes legal responsibility for the shipment.

LCL shipments generally, and NVOCC shipments specifically, can help counterfeiters obscure their illicit activities. With LCL shipments, counterfeiters can intermingle their illegitimate goods with the legitimate goods of others, giving their shipments the superficial appearance of legitimacy. With NVOCC shipments, counterfeiters are further able to hide the illicit origins of their goods as they are able to use a legitimate intermediary as a cover and shipper of record.

The multiple methods of shipping counterfeit goods via ocean-going container vessels also create multiple opportunities for product-counterfeiting intervention. Such methods, however, must account for multiple layers of responsibility in such shipments as well as difficulty in identifying the source of counterfeit goods. Both of these can greatly increase as additional intermediaries become involved in the shipping process. OTIs provide invaluable services to importers and exporters, particularly when LCL shipping is required. At the same time, these services can be indispensable facilitators to product counterfeiters seeking to hide the illicit nature of their goods.

Role of Shipping Vessels in Counterfeit Trade

Beyond freight consolidators and similar firms, ocean-going shipping companies themselves may become facilitators, knowingly or not, in the shipment of counterfeit goods. Some shipping companies when made aware that their vessels and containers are being used to ship counterfeit goods become active partners in identifying counterfeiting activities. For example, Nike representatives in Europe have worked with shipping and trucking companies to identify shipments of counterfeit goods that may pass through these carriers (Willamette Week, 2011). Working with brand owners to identify counterfeiters and prevent them from using their services allows shipping companies to become partners in anti-counterfeiting efforts, effectively increasing a brand owner’s guardianship within the distribution stream.

A possibly more witting example of shipping-company complicity in product counterfeiting is the growth of Chinese-based global container-shipping company Cosco and its connection to the rise of product counterfeiting in Greece. Some sources assert that Cosco is at the very least overlooking the problem while Cosco denies the claims and maintains its stance as a partner in efforts to fight the proliferation of counterfeit goods (Het Financieele Dagblad, 2011). Because the majority of counterfeit goods originate in China and other southeast Asian countries (European Commission, 2015; Turnage, 2013), it is reasonable to assume that the shipping companies with the largest presence in this region will carry the bulk of counterfeit goods, yet it cannot be assumed that these companies are complicit in counterfeit trade. This is especially true given China is the top seaborne trading partner for the United States, accounting for more than 64 million metric tons of legitimate goods valued at more than $300 billion (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

There is, however, some evidence that some shipping companies may seek to take advantage of the sprawling counterfeit manufacturing industry in China. One report (Goodman, 2004) of a Hong Kong facility where contract counterfeiters copy luxury goods on a vast scale noted how a representative of the freight forwarding company Hsien Shih Co. described that his company could provide complete logistics services of counterfeit goods “anywhere by sea.” The report did not confirm whether this individual was an actual representative of Hsien Shih Co., but it raises the possibility that legitimate shipping companies, or some of their less-scrupulous representatives, are trying to take advantage of a growing and lucrative market in counterfeit trade. It must also be acknowledged that the individual described in the Washington Post report could have simply been misrepresenting himself as a legitimate agent of Hsien Shih Co.; he could have been a “counterfeit” shipping agent. Counterfeiters have become very adept at forging and falsifying shipping documents and paperwork, and it is not inconceivable that some have set up a shipping operation catering to counterfeit trade, while using the name, reputation, and intellectual property of a legitimate shipping company.

How Legitimate Intermediaries Become Partners in Product Counterfeiting

Very few legitimate transportation intermediaries are likely to actively market their services to counterfeiters. Nevertheless, counterfeiters may be courted, even if inadvertently, as potential customers in areas with a heavy concentration of counterfeiting operations. While the vast majority of companies providing ocean-going cargo-shipping services are likely to avoid participation in counterfeiting schemes, counterfeiters are very good at hiding their crimes from legitimate businesses, and may be very adept at capitalizing on procedural and structural weaknesses in using honest and unwitting, or negligent, companies to complete their criminal acts.

Using legitimate shipping services to move counterfeit goods means that product counterfeiters need to fool the OTIs and vessel operators into thinking the product being transported is something other than what it seems. Counterfeiters use several tricks to do this, including false product documentation, providing false shipper or receiver information, and falsifying customs documents and other official forms. These methods seek to fool both shipping companies and Customs officials at the destination port-of-entry into believing that the cargo in the container is legitimate goods. OTIs and shipping companies are likely aware that they are being used as unwitting partners by counterfeiters. For example, the website for Missouri-based Eckhard Shipping Company warns visitors about counterfeit bills of lading bearing the company’s information.

It is not difficult for counterfeiters to falsify shipping and Customs documents, as only a minimum amount of information is required to complete these forms. Counterfeiters who pay careful attention to their craft are able to coordinate their activities in such a way as to avoid raising suspicions by completing paperwork in a way that appears legitimate. They may do so, for example, by listing a fictitious product that is being shipped from a credible source to a believable destination. One large counterfeiting scheme unraveled when U.S. Customs agents inspected a cargo container listed as carrying handbags, while the importer of record was described as a home-and-garden store (Wright & Baur, 2013). The counterfeiter’s decision to list a home-and-garden store, an unlikely site for handbag sales, led to discovery of counterfeit Hermes luxury handbags valued at nearly $200 million.

Transportation companies may choose not to qualify their customers, or to detect possible counterfeiters, beforehand for several reasons. First, some may be complicit with counterfeiters and therefore refrain from Know Your Customer (KYC) activities. Second, the ambiguity and complexity that surround the shipment of goods via ocean-going vessels, particularly when multiple intermediaries are involved, can help counterfeiters hide their schemes, or make them too complex for transportation companies to detect them with reasonable efforts. Third, shipping has become an extremely competitive business, and excessive investigations into a customer’s dealings may turn away legitimate businesses. Ocean-going shipping container companies, freight forwarders that deal with LCL shipments, and NVCCOs face a wide range of issues, including the need to fill containers and ships, to generate sufficient revenue for their infrastructure, and to grow or maintain market share within a competitive marketplace (Notteboom, 2004). These issues may lead some companies in the container-shipping business to make decisions that unintentionally increase the use of their services by product counterfeiters, while decreasing their ability to detect counterfeiting activities.

Creating Accountability and Assisting with Counterfeit Prevention

OTIs and shipping-vessel operators have a responsibility to act on behalf of their legitimate customers (i.e., brand owners) and actively engage in anti-counterfeiting activities to reduce the likelihood that they could become partners in the counterfeiters’ games. This springs from norms and values associated with corporate social responsibility (CSR). Formal methods of creating responsibility relate to the use of legal standards such as contributory or vicarious liability, while more informal methods may involve industry and brand-owner efforts to create and enforce a strong culture of accountability. Below we review in detail the responsibility OTIs and shipping-vessel operators have to mitigate the product-counterfeiting trade, and the means they can use to exercise this responsibility.

Socially Responsible Behavior

CSR “refers broadly to actions that businesses and corporations voluntarily undertake both to promote social and environmental goals and to minimize potential social and environmental costs associated with business activities” (Clapp and Rowlands, 2014). CSR principles lead corporations to acknowledge that they have duties to a range of stakeholders throughout society, duties that extend beyond profits. CSR principles would direct transportation intermediaries to consider the role they play in activities such as product counterfeiting that exact significant harms on human health and safety, before considering potential profits (or losses). In essence, CSR principles would guide these companies to ensure that business practices are established to prevent, as far as possible, the provision of services to product counterfeiters, even if such a directive reduces profits and affects market share.

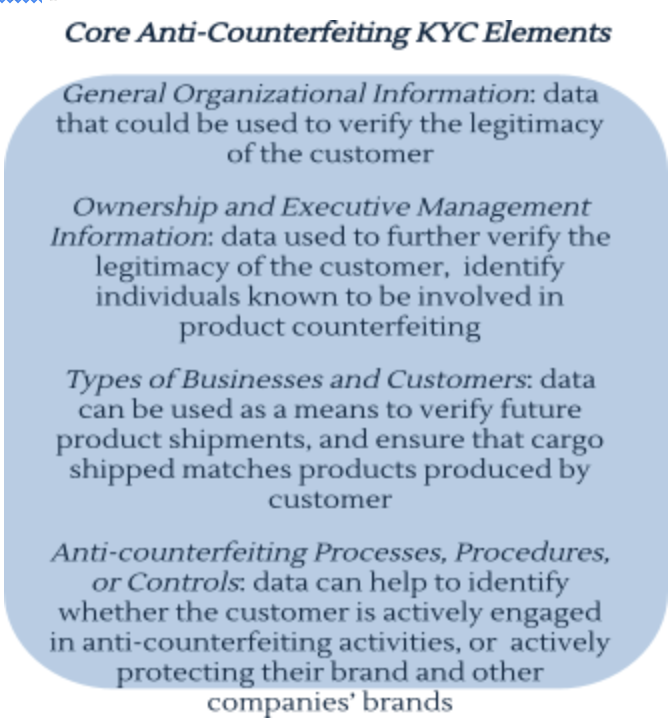

Socially responsible behavior can include undertaking, or strengthening, KYC policies and procedures so as to become more active in anti-counterfeiting activities by denying services to individuals and organizations known to be involved in product counterfeiting. KYC programs are most prominently associated with the banking industry and rules that govern policies and procedures related to anti-money laundering activities (Tuba & van der Westhuizen, 2014). KYC processes have also been used to boost the effectiveness of customer relationship-management practices (Mullins et al., 2014; Ramesh, 2014) as well as to develop new marketing strategies (Dalgic & Leeuw, 2015). Regardless of context, KYC leads companies to understand the nature and identity of their customers. BASCAP (2015) suggests that KYC programs can effectively broaden the range of responsibilities shipping companies have to prevent the flow of counterfeit goods across the globe—responsibilities they may fulfill by creating incentives for intermediaries to adopt and maintain standards that support brand protection and risk mitigation.

Businesses identifying customers prior to the provision of services that may facilitate illegal behavior engage in a proactive anti-crime initiative (Gill & Taylor, 2004). Because KYC requirements are not currently stipulated for companies involved with ocean-going container-shipping, the adoption of these practices would reflect socially responsible corporate behavior in which transportation intermediaries go above and beyond what they are legally required to do to protect brand owners and consumers. KYC practices, however, may be feasible only when an on-going or established supplier relationship is the intent. This does not mean that OTIs and vessel operators need to push customers to work exclusively with them (although this has several benefits for the shipper), but rather that they should approach customer relationships as if there will be continued and sustained interaction. This would necessitate the sharing of information between the customer and the intermediary, and provide a solid basis for the use of KYC policies and procedures.

A useful framework for developing KYC anti-counterfeiting guidelines in ocean-going cargo-container shipping can be drawn from the finance industry, which uses formal procedures for determining whether customers are part of larger anti-terrorism and anti-money laundering efforts. A particularly instructive example of KYC standards is provided in the Correspondent Account KYC Toolkit, a publication developed by the International Finance Corporation’s (2009) World Bank Group. This publication lays out a series of core pieces of information that should be obtained when conducting a comprehensive KYC analysis, and that can be adapted to fit the anti-counterfeiting efforts related to transportation intermediaries. Core anti-counterfeiting KYC principles would require an intermediary to gather the following types of information about its customer:

General Organizational Information. Includes data that could be used to verify the legitimacy of the customer includes

- Record of incorporation or other document stating the legal status of the organization

- Licenses for contract manufacturing or packaging on behalf of another corporation

- Address of the main office

- Information about subsidiary organizations (if relevant)

Ownership and Executive Management Information. Information used to verify the legitimacy of the customer, as well as identify the key individuals of the firm and to identify those known to be involved in product counterfeiting. Such information may include

- Copies of annual reports or other company documents describing products, executives, and activities

- Names and brief background of key personnel

- Ownership information, including information on principal owners not involved in executive management

- Information on corporate governance

Types of Businesses and Customers information can be used to verify future product shipments and ensure that cargo being shipped under the customer’s name matches the types of products being produced by the customer. Such information may include

- List and descriptions of products manufactured, including those manufactured under contract for another company

- List and description of customer’s primary markets and target customers

- List of places to which customer routinely ships products via cargo container.

Anti-counterfeiting Processes, Procedures, or Controls. Information that can help the intermediary identify whether the customer is actively engaged in anti-counterfeiting activities designed to protect brand owners. Such information can include

- The organization’s anti-counterfeiting strategic plan

- Information about active brand protection activities

- Anti-counterfeiting policies and procedures

- Contact information for key brand protection personnel, if relevant

These elements are simply suggestions for a standardized KYC policy to be used by OTIs and vessel operators to vet potential customers and actively engage in anti-counterfeiting activities. Because a standardized KYC program is not likely to become a regulatory reality in ocean-going cargo shipping, the responsibility for implementing, revising, and overseeing KYC processes will rest with brand owners who wish to involve their supplier partners in brand-protection efforts. In the end, KYC procedures like those suggested here are just one step towards creating accountability within companies that may facilitate the movement of counterfeit goods across the world.

Creating Accountability

KYC processes are an important part of enhancing anti-counterfeiting accountability in the business of ocean-going cargo container shipping, but some form of oversight is needed for these and other methods of accountability to carry weight and legitimacy. CSR principles have proliferated in many years, yet gaining industry compliance has been difficult, as market forces may push companies to focus on profits to the exclusion of socially responsible behavior (Lim & Phillips, 2008). Nevertheless, governments, non-governmental organizations, and consumers can often push for socially responsible supply-chain decisions (Hoejmose & Adrien-Kirby, 2012), while shareholders may also exert pressure to implement standards of accountability.

Brand owners, as consumers of the services provided by OTIs and container-shipping companies, can have a tremendous influence on creating accountability by serving as Corporate Social Watchdogs (Spence & Bourlakis, 2009). In this role, brand owners take responsibility for setting and enforcing accountability standards, ensuring that transportation intermediaries understand that product counterfeiting is a problem they share a responsibility to prevent. This duty should not become a means of controlling or directing the activities of intermediaries, as such a situation can strain important business relationships and lead to less productive partnerships (Boyd et al., 2007).

A more meaningful and influential method of creating accountability may be peer-firm influence, which may be a greater motivator than the threat of regulatory action (Park-Poaps & Rees, 2010). Self-regulation allows the firms within an industry to select the types of behavior considered deviant or harmful, and gives these firms the ability to handle violations according to established industry standards. For transportation intermediaries engaged in international trade, a pure self-regulation model is not possible as national and international laws affect the shipment of goods across borders. Nevertheless, a partial self-regulatory scheme may be possible, where peer firms establish extra-legal rules, norms, and standards related to anti-counterfeiting processes and procedures and monitor each other for compliance.

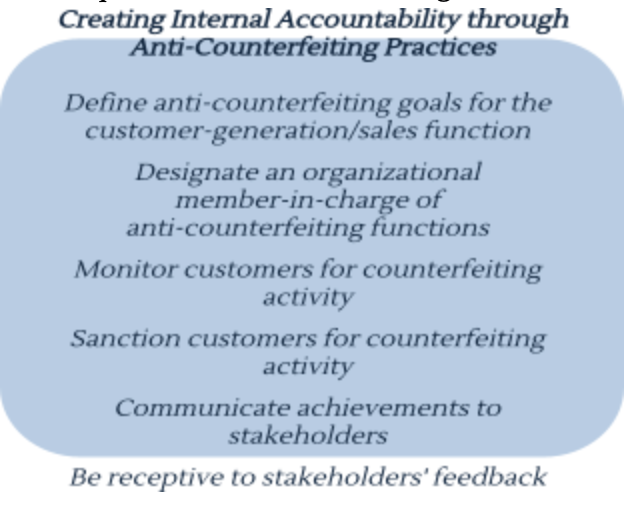

Under a partial self-regulatory scheme, non-governmental agencies, such as the World Customs Organization, together with OTIs and container-shipping companies, would work with relevant stakeholders to create internal accountability standards. These would include procedures that, together with the KYC procedures discussed above, enhance efforts to address the use of shipping services by product counterfeiters. Using a non-economic criteria purchasing process outlined by Maignan, Hillebrand and McAllister (2002), we develop a process transportation intermediaries can use to institute anti-counterfeiting activities. This process involves the following six steps.

STEP ONE: Defining anti-counterfeiting goals for the customer-generation/sales function. Setting anti-counterfeiting goals for customer-generation does not necessarily mean setting metrics on identifying customers who may be engaged in counterfeiting. Rather, these goals relate to more global benchmarks, such as having no containers seized by a Customs agency for counterfeiting offenses, or achieving total transparency with injured brand owners when counterfeit goods are shipped using the company’s services. These goals may be difficult to quantify and should not have metrics that are assessed in the same manner as other performance targets. Instead, these goals should set the tone for the remainder of the process and reflect the intermediary’s approach to anti-counterfeiting activities.

STEP TWO: Designating organizational members-in-charge of anti-counterfeiting functions. One or more organizational members must be responsible for ensuring that anti-counterfeiting practices are implemented and followed within the company. These positions can be externally visible (i.e., a position that regularly interfaces with customers, partners, suppliers, and others regarding anti-counterfeiting practices), but this is not a necessity. What is necessary is that at least one individual be given responsibility for coordinating and leading internal anti-counterfeiting efforts.

STEP THREE: Monitoring customers for counterfeiting activity. Guided by elements of the KYC procedures described above, intermediaries can continually monitor their customers and partners for evidence of counterfeiting activity. Companies should not take on the role of law enforcement and initiate high-level investigations in search of counterfeiting activity. Rather, they should maintain an active monitoring program to identify and record information about counterfeiting activity associated with their services, containers, or vessels.

STEP FOUR: Sanctioning customers involved in counterfeiting. When evidence of counterfeiting activity is identified and verified, whether it be in the KYC process or upon official notification that a cargo container held counterfeit goods, intermediaries must take action and sanction the customer in some way. This can include refusing to do business with the customer, suspending customer accounts for a period of time, or turning over relevant information to law enforcement and brand owners to assist with lawful investigations.

STEP FIVE: Participating in formal anti-counterfeiting organizations. By participating in the same anti-counterfeiting organizations as stakeholders, OTIs and container-shipping companies can communicate their active commitment to protecting brand-owners’ rights. While there are currently no formal methods for certifying the anti-counterfeiting activities of transportation intermediaries, becoming active in anti-counterfeiting organizations will allow them to share information with stakeholders, as well as with each other. Formal anti-counterfeiting organizations can facilitate many informal (and formal) relationships, which can enhance the influence of industry peers and stakeholders.

STEP SIX: Receiving stakeholders’ feedback. Companies that are interested in strong stakeholder relationships will illicit feedback from important constituents on a continual basis as part of an active program of self-improvement. This feedback can help intermediaries identify areas for improvement, as well as to objectively evaluate progress in anti-counterfeiting activities. Ultimately, the processes of receiving stakeholder feedback, whether formal or informal, represent a way for companies to continually improve their proactive anti-counterfeiting processes. Combined with KYC procedures, these processes can help OTIs and vessel operators effectively stem the tide of counterfeit goods that flow through their business.

Vicarious and Contributory Liability

While transportation companies may rarely, if ever, knowingly assist product counterfeiters in moving their goods, such companies may still bear liability for harms such goods cause to legitimate producers and others. In particular, they may face vicarious or contributory liability. The prospects of such liability may, ultimately, boost use of KYC processes and anti-counterfeiting procedures.

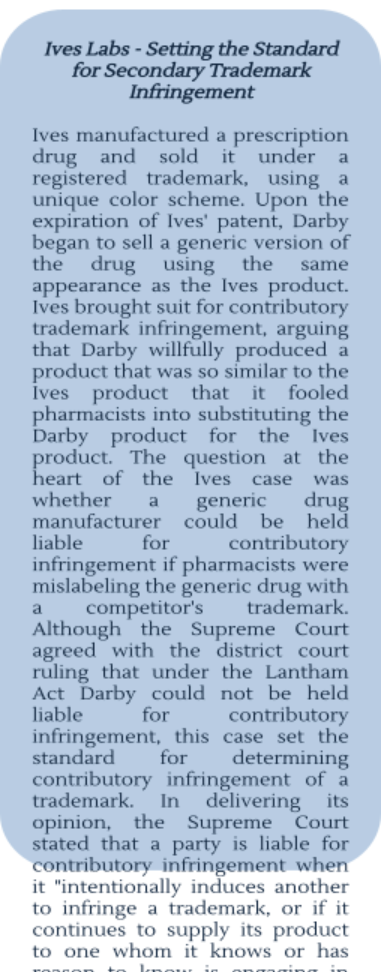

Contributory liability for trademark infringement requires a higher burden of proof than vicarious liability, as the third party must know of the infringement and materially contribute to the infringement in some way (Lichtman & Landes, 2002). Specifically, contributory infringement requires first, that the shipper know of the counterfeiting activity, and second, that the shipper materially contribute to the infringement (McCue, 2012). By providing essential transportation services, OTIs and container-shipping companies may materially contribute to counterfeiting activity, but it is very difficult to prove that a shipper knew it was transporting counterfeit goods.

Vicarious liability for trademark infringement also has two standards: first, that a third party has the right and the ability to control the actions of the counterfeiter, and second, that the third party receives a financial benefit from the counterfeiting (McCue, 2012). Again, there is no question that OTIs and ocean-going cargo container-shipping companies receive a financial benefit from counterfeit goods that are shipped by them, as counterfeiters pay shipping costs like any legitimate manufacturer. Transportation intermediaries also have the right to refuse to do business with individuals and organizations involved in criminal activity; indeed, the criminal indictments of FedEx and UPS clearly identify this as a right and responsibility borne by contract shippers.

Whether transportation intermediaries can control the actions of counterfeiters so as to control counterfeiting activities is perhaps an open question. Counterfeiters will use deceit and false documents to fool intermediaries into believing that their cargo is legitimate. At the same time, perhaps anti-counterfeiting processes such as those described above can help stop some of this deception. Accordingly, the proliferation of KYC processes and the standardization of anti-counterfeiting procedures may create an environment where OTIs and shipping companies become increasingly liable for counterfeiting activity under a standard of vicarious liability. Increased use of vicarious-liability standards in counterfeiting cases may lead to more formalized KYC and anti-counterfeiting procedures among container-shipping companies as they seek to do all they can to prevent their involvement in activities that infringe upon brand owners’ intellectual property rights.

Summary and Conclusion

Product counterfeiters will use any number of methods to ship their illegitimate goods to consumers. To ship smaller quantities directly to consumers, product counterfeiters may use express services or the postal system. To move large quantities of goods, product counterfeiters usually rely upon cargo shipments and ocean-going shipping vessels, particularly for goods that must travel long distances, such as those manufactured in Southeast Asia and destined for Europe or the United States. OTIs and container-shipping companies likely do not seek product counterfeiters as customers; rather, given the option, legitimate shipping companies would chose not to serve counterfeiters.

Yet, counterfeiters are not open and honest about their business, and they routinely use falsified shipping documents, as well as other illegal means, to ensure their goods are shipped around the world. By disbursing manufacturing, packaging, and distribution operations across multiple locations, and taking advantage of structural weaknesses in shipping procedures, organized groups of product counterfeiters can conceal the true nature and origin of products. This makes it easier to pass counterfeit goods as non-descript items with no illegitimate intent, allowing counterfeiters to fool container-shipping companies into moving them.

The implementation of KYC procedures and anti-counterfeiting processes focusing on the customer generation and sales can help transportation intermediaries be more selective regarding customers. While it is common for counterfeiters to falsify paperwork and use legitimate companies to conceal their illegal activities, the diligent and consistent use of anti-counterfeiting strategies can help reduce the amount of counterfeit goods that enter the supply chain. Yet, the high fixed costs of operation for ocean-going cargo shippers, freight forwarders, and NVOCCs may make it difficult for some companies to justify that may turn potential customers away before determining whether their business is legitimate.

KYC programs may undermine the relationships a company has with its customers by transforming the company into an agent of the government rather than an agent of the customer (Hall, 1995). Yet, the paperwork and recordation requirements that currently apply to OTIs and ocean-going shipping companies already make them agents of the government. KYC programs would help intermediaries take accountability for their role in preventing product counterfeiting, and allow them a tangible and measurable way to assist governments, law enforcement and brand owners in their anti-counterfeiting efforts.

Whenever counterfeiters ship products, the companies providing the shipping and ancillary services receive a profit. This does suggest that shipping companies are complicit in the counterfeiter’s illegal activity, but rather underscores the fact that legitimate corporations benefit from counterfeiters’ ill-gotten gains. This creates a potential dilemma for intermediaries as they may deny services to potential customers they know or suspect are engaged in counterfeiting, yet in doing so would deny themselves profits. When potential customers are clearly engaged in illegal activity, the conflict between profit and complicity is easily resolved, but uncertainty in the legality of a potential customer’s activities creates a dilemma. The use of KYC procedures can help resolve such dilemmas.

References

BASCAP. (2015). Roles and Responsibilities of Intermediaries: Fighting Counterfeiting and Piracy in the Supply Chain. Paris, France: International Chamber of Commerce.

Benson, M. L., & Simpson, S. S. (2009). White Collar Crime: An Opportunity Perspective. New York: Routledge.

Boyd, D. E., Spekman, R. E., Kamauff, J. W., & Werhane, P. (2007). Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains: a procedural justice perspective. Long Range Planning, 40(3), 341-356.

Clapp, J., & Rowlands, I. H. (2014). Corporate social responsibility. In Morin, J-F and Orsini, A. (Eds.) Essential Concepts of Global Environmental Governance. New York: Routledge.

Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute. (No date). Contributory infringement. Retrieved May 20, 2015 from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/contributory_infringement.

Dalgic, T., & Leeuw, M. (2015). Niche marketing revisited: theoretical and practical issues. In Proceedings of the 1993 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference (pp. 137-145). Springer International Publishing.

European Commission. (2015). Taxation and Customs Union – Counterfeit and Piracy. Retrieved May 25, 2015 from http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/customs/customs_controls/counterfeit_piracy/international_cooperation/ index_en.htm.

FedEx. (2015). About FedEx. Retrieved May 20, 2015 from http://about.van.fedex.com/fedex _corporation.

Gill, M., & Taylor, G. (2004). Preventing money laundering or obstructing business? Financial companies’ perspectives on ‘know your customer’ procedures. British Journal of Criminology, 44(4), 582-594.

Goodman, P. (2004, July 12). In China, a growing taste for chic. But fakes also vex developing market. Washington Post. Retrieved March 10, 2015, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A43030-2004Jul11.html.

Grant, J. (2013, October 22). Passaic Co. man sentenced for role in China-to-U.S. smuggling scheme. NJ.com. Retrieved May 29, 2015 from http://www.nj.com/passaic-county/index.ssf/2013/10/passaic_co_man_sentenced _for_role_in_china-to-us_smuggling_scheme.html.

Hall, M. R. (1995). Emerging Duty to Report Criminal Conduct: Banks, Money Laundering, and the Suspicious Activity Report, An. Ky. LJ, 84, 643-684.

Het Financieele Dagblad. (2011, August 1). A tidal wave of counterfeit products floods Europe via Greece. Het Financieele Dagblad. Retrieved March 10, 2015 from http://fd.nl.

Hoejmose, S. U., & Adrien-Kirby, A. J. (2012). Socially and environmentally responsible procurement: A literature review and future research agenda of a managerial issue in the 21st century. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 18(4), 232-242.

International Finance Corporation. (2009, October). Correspondent Account KYC Toolkit: A Guide to Common Documentation Requirements. Washington, D.C.

Lichtman, D., & Landes, W. (2002). Indirect liability for copyright infringement: an economic perspective. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 16, 395-410.

Lim, S. J., & Phillips, J. (2008). Embedding CSR values: The global footwear industry’s evolving governance structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(1), 143-156.

Maignan, I., Hillebrand, B., & McAlister, D. (2002). Managing socially-responsible buying: How to integrate non-economic criteria into the purchasing process. European Management Journal, 20(6), 641-648.

McCue, M. (2012, February). Secondary Liability for Trademark and Copyright Infringement. Paper presented at the 2012 Utah Cyber Symposium. Retrieved March 13, 2015 from http://www.lrrlaw.com/secondary-liability-for-trademark-and-copyright-infringement-02-05-2012/#.VRFe4OHNu1k.

Mullins, R. R., Ahearne, M., Lam, S. K., Hall, Z. R., & Boichuk, J. P. (2014). Know Your Customer: How Salesperson Perceptions of Customer Relationship Quality Form and Influence Account Profitability. Journal of Marketing, 78(6), 38-58.

Notteboom, T. E. (2004). Container shipping and ports: an overview. Review of network economics, 3(2), 86-106.

Palladino, V. (1982). Trademarks and competiton: The Ives case. John Marshall Law Review, 15, 319-356.

Park-Poaps, H., & Rees, K. (2010). Stakeholder forces of socially responsible supply chain management orientation. Journal of business ethics, 92(2), 305-322.

Ramesh, K. (2014). Role of Customer Relationship Management in Indian Banking System. International Journal of Applied Services Marketing Perspectives, 2(4), 645-650.

Spence, L., & Bourlakis, M. (2009). The evolution from corporate social responsibility to supply chain responsibility: the case of Waitrose. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 14(4), 291-302.

Stevens, L. (2014, August 15). FedEx Faces Additional Charges in Prescription-Drug Delivery Case

New Indictment Accuses Company of Conspiracy to Launder Money. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 14, 2014 from http://www.wsj.com/articles/fedex-faces-additional-charges-in-prescription-drug-delivery-case-1408145975.

Tuba, M., & van der Westhuizen, C. (2014). An analysis of the ‘know your customer’ policy as an effective tool to combat money laundering: is it about who or what to know that counts? International Journal of Public Law and Policy, 4(1), 53-70.

Turnage, M. (July 25th, 2013) A mind-blowing number of counterfeit goods come from China. Business Insider. Retrieved May 25, 2015 from http://www.businessinsider.com/most-counterfeit-goods-are-from-china-2013-6.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). FT920: U.S. Merchandise Trade: Selected Highlights. Retrieved March 24th, 201, from http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/2014pr/12/ft920.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection – Office of International Trade. (2013). Intellectual Property Rights Fiscal Year 2013 Seizure Statistics. Retrieved October, 2014, from http://www.cbp.gov/trade/priority-issues/ipr/statistics.

U.S. DOJ, 2014. FedEx Indicted For Its Role In Distributing Controlled Substances And Prescription Drugs. Retrieved April 14, 2014 from http://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/pr/fedex-indicted-its-role-distributing-controlled-substances-and-prescription-drugs.

U.S. FDA, 2013. UPS Agrees to Forfeit $40 Million in Payments from Illicit Online Pharmacies for Shipping Services. Retrieved April 14, 2014 from http://www.fda.gov/iceci/criminalinvestigations/ucm347457.htm.

United States of America v. Aref Abuhadba. (2013). Retrieved May 29, 2015 from http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-nj/legacy/2013/11/29/Abuhadba,%20Aref%20Information.pdf.

Willamette Week. (2011, December 14). Nike representative describes counterfeit goods smuggling in Croatia. Willamette Week. Retrieved March 10, 2015, from http://wweek.com/portland/article-18471-nike-representative-describes-counterfeit-goods-smuggling-in-croatia.html

World Intellectual Property Review. (2014, August). Millions of Counterfeit Cigarettes Seized from EU Shipping Containers. Retrieved March 5, 2015, from http://www.worldipreview.com/news/millions-of-counterfeits-seized-from-eu-shipping-containers-7273.Wright, D. & Baur, B. (2013, October 21). LAPD, US Customs battle counterfeit goods market, multi-billion dollar industry more lucrative than drugs. ABC News. Retrieved March 10, 2015, from http://abcnews.go.com/US/lapd-us-customs-battle-counterfeit-goods-market-multi/story?id=20639145.

2015 Copyright Michigan State University Board of Trustees.