Emily Osika, 2019

Abstract

The role of international cooperation through several transnational bodies provides countries the ability to cooperate on trademark enforcement mechanisms, allow for, and develop a global agenda on trademark enforcement. This is important because trademark violations are a global concern, in which countries and industries share an invested interest. Between the United States, China, and Brazil, international cooperation has aided in the spread of information and joint enforcement operations; however, barriers to cooperation still persist. Such barriers hinder the spread of information, as well as enforcement capabilities on a global scale. These limitations allow for the continuation of trademark violations; hence, the ability to purchase counterfeit goods in the global marketplace remain prevalent. The methods to eliminate barriers are complex; therefore, they require a unified effort from the international community to help reduce the production and spread of counterfeit goods.

Key terms: Intellectual property, counterfeit, enforcement, cooperation, barriers

Introduction

Global connections are pertinent to solving international issues, and trademark protection is no exception. A trademark is defined as “any word, symbol, design, colour or sound that is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another” (Hiney & Mottes, 2017, 246). A rising global concern involves the act of trademark infringement, which is a violation of a brand’s registered trademark. Protecting a brand owners’ intellectual property, or the creation of a product and what makes it unique including its “artistic expressions, signs, symbols and names used in commerce, designs and inventions,” is crucial in facilitating an atmosphere that encourages innovation in the global marketplace (Understanding the WTO: Intellectual,” n.d.). Trademark infringement through the creation, production, and sale of counterfeit goods, which is the “illegal or unauthorized manufacturing of goods,” is violation of a registered trademark (Chikada & Gupta, 2017, 343). The counterfeit is when the violated trademark is placed upon a product, and this issue is a challenge that countries share an invested interest in the enforcement and restriction of within global trade.

International cooperation through various organizations and legal entities broaden global trademark enforcement efforts through the enhancement of information gathering and joint enforcement application. Countries such as the United States, China, and Brazil help demonstrate the domestic and international enforcement mechanisms that affect the success of trademark enforcement on the global stage. However, barriers exist connected to culture, seriousness of enforcement and engagement, and technological difficulties that affect the level of enforcement success in deterring intellectual property crimes.

This paper will begin by reviewing trends in counterfeit activity between 2013 and 2016 among the United States, China, and Brazil. This will be followed by an analytical overview of each country’s individual legislation regarding trademark protection and domestic enforcement mechanisms. Next, the role of international cooperation through the World Trade Organization (WTO), Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), Interpol, and World Customs Organization (WCO) will be specified and later evaluated by documented outcomes and their impact on trademark enforcement. After, this paper will attempt to understand what barriers are present that hinder international cooperation towards controlling the flow of counterfeit goods. Lastly, future predictions and recommendations for the lasting impact and success of global cooperation on intellectual property enforcement.

Section 1: Framework

A: Trends in Counterfeit Activities: 2013-2016

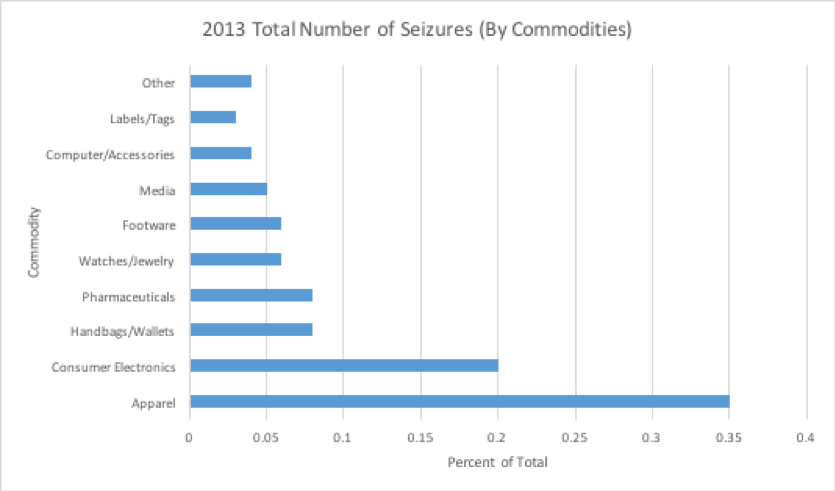

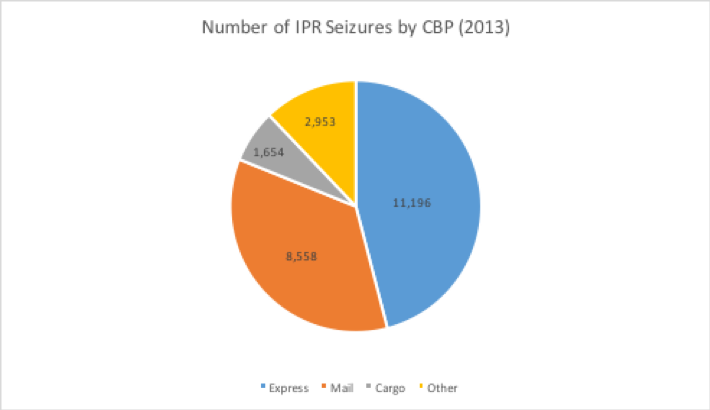

During fiscal year 2013, the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was a main actor in documenting counterfeit seizures from across the globe. According to reports from CBP in 2013, the amount of seizures nearly increased from 2012 to 2013 by a staggering 7%, from 22,848 to 24,361 seizures (OT, 2013). The top source for counterfeit goods originated from the People’s Republic of China, encompassing 68% of the total intellectual property seizures, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reported the goods to be of value of US$1.1 billion (OT, 2013). The total number of seizures, based on commodities in 2013, was apparel at 35% followed by consumer electronics at 20% of the total amount seized (Figure A) (OT, 2013). Environment seizures in 2013, categorized by express, cargo, mail, and other, were mainly seized by express methods at 11,196 counterfeits (Figure B) (OT, 2013).

(Figure A)

(Figure B)

According to the IP Commission Report, 68% of the counterfeit products that entered the US in 2013 came from China (NBR, 2017). Surprisingly, between the years 2011-2013, “Chinese brands were the 13th most hit by counterfeiting and piracy,” while Brazilian brands affected by counterfeiting were ranked 23rd across the world (OECD BRICS, 2018, 145). According to the PRC’s National Intellectual Property Administration report, in 2013, 2328 cases were accumulated in China for counterfeit goods with the most amount of cases, 451, accumulated in the Shandong region (“State Intellectual Property,” 2013).

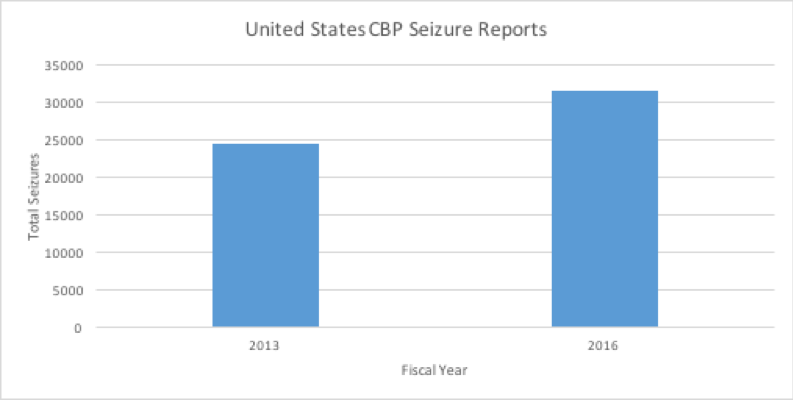

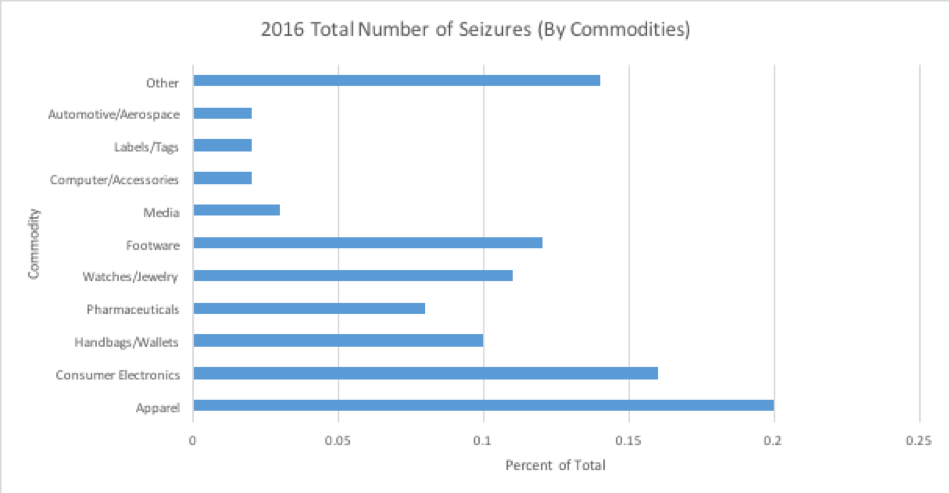

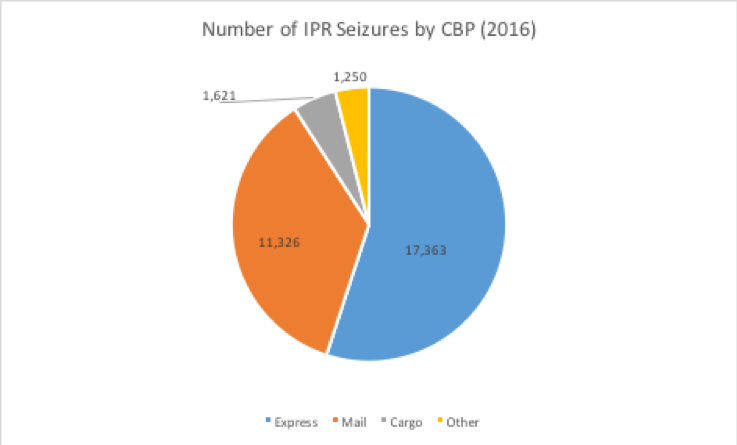

Progressing to fiscal year 2016, the amount of CBP seizures reached new heights of 31,560 seizures, which was a 9% increase from 2015, and is displayed in Figure C (OT, 2016). The total number of seizures, based on commodities in 2016, was apparel leading at 20% followed by a clear rise in counterfeit footwear and watches/jewelry seizures (Figure D) (OT, 2016). Environment seizures in 2016, categorized by express, cargo, mail, and other, were still mainly seized by express methods at 17,363 counterfeits with a larger proportion than in 2013 (Figure E) (OT, 2016). Out of the 2016 total seizures, 16,417, or 52%, were sourced coming from the Chinese economy (OT, 2016). The consistent increase in the amount of seizures of counterfeit goods displays an apparent rise in total counterfeit activity in the global arena.

(Figure C)

(Figure D)

(Figure E)

As a whole, “the US 2016 and 2015 Notorious Markets List reported that China is the manufacturing hub of counterfeit products sold illicitly in markets around the world” (OECD “China,” 2018, 186). The PRC published a report in 2016 that confirmed that a total of 9,288 counterfeit cases were accumulated in China, which was 6,960 more cases than in 2013 (“State Intellectual Property,” 2016). This conclusion is further supported by the World Customs Organization 2016 Illicit Trade Report, which emphasizes the role of Asian nations, specifically China, as the source economies of illicit intellectual property trafficking. For instance, the trade flows in 2016 show that counterfeits produced were primarily exported from either China or Hong Kong, with 51.1% of the trafficking paths stemming from the region (WCO, 2017). A large quantity of the counterfeit trafficking networks, 7,074 counterfeits, led to the US, while countries in South America retrieved most of their counterfeits from the United States (WCO, 2017). In essence, counterfeit activities are a global enterprise that creates a need for more advanced enforcement measures. Domestic and international enforcement mechanisms play an important role in attempting to strengthen and protect intellectual property in the global marketplace.

B: Government Role, Law, and Enforcement Mechanisms

In the United States, Title 15 U.S.C. Section 1127 defines a “trademark” as “any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof used by a person, or which a person has a bona fide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this Act, to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown” (United States Code Service, 2018). Within the Federal Statute, a “counterfeit” is defined as “a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark” (United States Code Service, 2018). Trademark protection has been an increasing priority for industries, the government, and consumers alike in the United States. The federal statute that governs trademark law is the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1051). Under §1 (15 U.S.C. § 1051), the Lanham Act indicates that “the owner of a trademark used in commerce may request registration of its trademark on the principal register hereby established by paying the prescribed fee and filing in the Patent and Trademark Office an application and a verified statement” (Trademark Act of 1946, 2013, 7).

The federal statute also provides the “enforcement of trademarks, service marks and unfair competition” (Hiney & Mottes, 2017, 245). Specifically, for a trademark to receive anti-counterfeiting law protection, it must first be registered by the owner through the US Patent and Trademark Office (Wadyka Jr et al., 2016).

For enforcement of trademark infringement, the federal statute 18 USC Section 2320 is the mechanism for criminal punishment. The federal statute outlines that if an individual commits an act of counterfeiting, the individual “shall be fined not more than $ 2,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both, and, if a person other than an individual, shall be fined not more than $ 5,000,000” (United States Code Service, 2018). While numerous offenses increase the level of payment and punishment, the actual implemented punishments are usually not as severe. Recently, an act signed into law to aid in the protection of IP rights was the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (TFTEA). Signed into law on February 24, 2016 by Former President Obama, the act was intended to facilitate a competitive, yet fair environment designed for trade activities (“CBP and the Trade,” 2018).

According to TFTEA, the act “shall establish priorities and performance standards to measure the development and levels of achievement of the customs modernization, trade facilitation, and trade enforcement functions and program” (TRADE FACILITATION AND TRADE ENFORCEMENT ACT OF 2015, 2016). Under Title III Section 305, “The Secretary of Homeland Security shall– establish within U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement a National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center” (TRADE FACILITATION AND TRADE ENFORCEMENT ACT OF 2015, 2016). This center helps coordinate the efforts of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS-ICE) with CBP to help contain the flow of goods that violate intellectual property rights (TFTEA, 2016). Essentially, both administrations will coordinate enforcement operations, training exercises, and education campaigns focusing on IP protection, which will be documented in a report delivered to Congress annually (TFTEA, 2016).

The core domestic IP enforcement mechanism within the U.S is the U.S Customs and Border Protection (CBP). This agency is associated with the Department of Homeland Security and is the main actor that prevents counterfeit goods from crossing the US border (Wadyka Jr et al., 2016). Establishing a trademark record with CBP, which costs $190 per product classification, helps brand owners protect their products through documented pictures and detailed information that CBP officials can utilize in order to recognize and apprehend counterfeits (Wadyka Jr et al., 2016). The development of a technological tool, called e-Recordation, is administered by CBP that right holders can access online to record their trademark administration, which is therefore available for CBP to easily examine across the nation (CBP, 2018).

One method of outreach the US is involved in is through the Global Intellectual Property Academy (GIPA). The academy’s main goal is engaging in intellectual property training for government officials domestically and around the world; however, headquarters are located in Alexandria, Virgina (“The Global Intellectual,” 2017). In 2016, around 5,000 officials from 114 foreign countries participated in GIPA training and topic discussions involving global intellectual property concerns (“The Global Intellectual,” 2017). The United States government has attempted to facilitate international cooperation measures to help broaden an area of concern that as a Western country, deem important to global business security. Relations with countries, like China, have become increasingly important for US strategies towards trademark enforcement.

China’s role in the international economy is one of increasing importance, especially with the dual titles as “the world’s manufacturer” and as the top consumer market, which makes China vital for any intellectual property cooperation operation (Plane & Livingston, 2016, 133). Debates around China’s international cooperation efforts on trademark enforcement are contentious; however, historical roots provide context for such accusations. Emphasized by the rule of Chairman Mao Zedong, the rise of communism developed an ideology that property rights were an insignificant norm for society (Mercurio, 2012). During this time, creation and innovation were rather discouraged, since all creations were labeled as “national assets” in the Cultural Revolution (Mercurio, 24, 2012). However, by the late 1970s, intellectual property rights began to take interest in China along with interactions with the global economy (Mercurio, 2012). Although China has introduced modern IP protection measures, other actors in the international system display dissatisfaction that China is not doing quite enough. For example, there is belief that local leaders are directly involved in counterfeit activities, which ultimately benefits the community “from employment and income distribution both directly in the manufacturing and indirectly through increased access to goods and support for the wider economy” (Mercurio, 26, 2012). Western businesses view China’s milder punishment towards IP violations as a reason large, domestic counterfeit operations view possible IP repercussions as merely the “cost of doing business” (Mercurio, 27, 2012).

Chinese Trademark law came into application in 1982; however, the document has been revised and amended in 1993, 2001, and most recently in 2013 (Wang & Zhang, 2014). The revised law was enacted by China’s National People’s Congress on May 1, 2014, and featured stronger enforcement protocols, including time limitations for different trademark prosecutions, as well as detailed infringement clarifications (Wang & Zhang, 2014). Most recently, on August 31, 2018, China developed and passed the PRC Electronic Commerce Law, which was deemed effective on January 1, 2019 (“China: E-Commerce,” 2018). The law asserts a stronger stance on Intellectual Property security by declaring if an IP rights holder.

“believes that an operator on a platform has infringed its IP rights, the IP rights holder may notify the platform operator and request the latter take necessary preliminary measures, such as deleting or screening information about the alleged infringement, disconnecting the relevant webpages, or terminating the transaction or service” (“China: E-Commerce” 2018).

In essence, if an IP rights owner witnesses or suspects that another e-commerce entity is violating his or her IP rights, the owner can request the operator of the e-commerce network to investigate. If there is no preliminary investigation upon request, the platform operator is therefore held accountable for any damages to the IP rights of the owner (“China: E-Commerce,” 2018). The strengthening of e-commerce regulations involving IP rights demonstrates an initiative in Chinese society to take trademark protection seriously for the promotion and continuation of creative innovation.

For current trademark registration, China employs a “File-to-File” system in which “trademark rights are awarded to the party that files first, rather than on the basis of prior use or intent to use” (Plane & Livingston, 2016, 133). This system can cause issues, especially if foreign brand owners are late to registering a trademark and a Chinese party files the registration documents first (“The world’s factory,” 2018). The Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, which was passed on July 1, 1979 and revised March 14, 1997, provides the framework for the criminal punishments for infringing on intellectual property rights. Within Section 7 Article 214, the National People’s Congress identifies that “Whoever knowingly sells commodities bearing counterfeit registered trademarks shall, if the amount of sales is relatively large, be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years or criminal detention and shall also, or shall only, be fined; if the amount of sales is huge, he shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not less than three years but not more than seven years and shall also be fined” (Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, 1997).

The reality in Chinese society is relatively weak punishments with minimal fines, and limited jail time, if any at all. With limited resources, police investigation may not even be followed up by prosecution through a court (Plane & Livingston, 2016).

Through the development and recognition of intellectual property rights within Chinese society, there has been a recent demand for the creation of courts to deal with such matters. Starting in August of 2014, the National People’s Congress officially established IPR courts in the Chinese cities of Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou (OECD, 2018, 176). These IPR courts were to have “jurisdiction over technically complex IPR cases, and appeals of basic civil and administrative IPR related decisions” (OECD, 2018, 176). Due to positive feedback on the construction of the courts, in 2017, a “three-year pilot program for specialized IP courts in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou” was established, and since then an increasingly number of IPR courts have continued to develop, as well as specialized IP tribunals (“Office of the United,” 2018, 39). The public response has been relatively positive and encouraging about the “competence, expertise and transparency” witnessed through court activities (“Office of the United,” 2018, 39). The most recent development has been the creation of an IP appeals court. Passed on October 26, 2018, the National People’s Congress designated “the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), the highest court in China, as the appeals court to hear ‘highly technical’ intellectual property (IP) cases” (“China: Supreme,” 2018). The expansion of courts gives indication of a possible national IP court being established in the near future, if support continues to remain strong (“China: Supreme,” 2018).

In addition to the IPR advancements in Chinese courts, domestic enforcement mechanisms are playing a larger role in Chinese society as well. Methods of outreach with the goal of information sharing and coordination between industries are key components of Chinese activities. For example, the Quality Brand Protections Committee (QBPC) was established in 2000 and involves around 200 multinational corporations broken up into committees and task forces (OECD “China,” 2018). The purpose of the Committee is to “strengthen Chinese IP laws and regulations, encourage IP creation, utilization, protection and management, improve the IP protection system, raise public awareness of IP protection and establish a long-standing and effective IPR protection system” (OECD “China,” 181, 2018). The goal is to facilitate smooth coordination between integral actors in Chinese society, like among local and national governments, as well as law enforcement professionals (Yang & Chen, 2016). Connections in the QBPC reach into the international arena, with relations with the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and World Customs Organization (WCO) all to aid in the sharing of information to foster a more open and engaged Chinese effort towards IP enforcement (Yang & Chen, 2016). Along with organizing training sessions with different industry actors, the Quality Brands Protection Committee also uses their influence to aid in guiding the Chinese government to strengthen IPR protection from a policy oriented approach through revising and improving new legislation (OECD “BRICS,” 2018).

Compared to its international neighbors, Brazil is a smaller destination and supplier of counterfeits worldwide. Brazil exports counterfeits predominately to its regional neighbors or historical trade networks, like those with Argentina and Portugal (OECD “BRICS,” 2018). Data analysis of counterfeit flows is rather limited in scope; however, estimates from non-governmental sources estimated the total amount of losses attributed to illicit trade was US$ 20 billion in 2014, which included contraband (“U.S. Department,” 2015). Since 2007, Brazil has been on the “Watch List” of the U.S. Trade Representative Special 301 report (“U.S. Department,” 2015), and the top brands counterfeited include products of footwear and glassware from the origins of China and Hong Kong (OECD “Brazil,” 2018). In contrast to Chinese society, the most harmful counterfeits come from the global economy, not national operations (OECD “Brazil,” 2018).

Legislation associated with trademark infringement is referenced in Article 130 of the Industrial Property Act (BIPA), which outlines that the “titleholder of a mark or the applicant is further assured the right to: assign his registration or application for registration; license its use; and safeguard its material integrity or reputation” (“Law on Industrial,” 1996). The National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) is the body of registration in Brazil to obtain legal trademark protection and it employs the “first-to-file” system (“The Services of INPI,” 2018). According to BIPA, a trademark is deemed infringed if a party “uses an identical or similar registered trade mark to cover identical or similar services or products, with no prior authorization or consent from the registered owner” (Fekete, Leonardo, & Advogados, 2018).

Additionally, Article 189 of the Industrial Property Act outlines criminal activities and consequences of trademark violations:

“A crime against mark registration is perpetrated by anyone who: reproduces a registered mark, in whole or in part, without the authorization from the titleholder, or imitates it in a way that may induce to confusion; or alters the registered mark of another person already affixed on a product placed on the market. Penalty—imprisonment, from 3 (three) months to 1 (one) year, or a fine” (“Law on Industrial,” 1996).

If a rights holder wants to conduct a lawsuit on a trademark infringement, the case will involve a private criminal prosecution operated at the Brazilian state court level (Leonardos, 121). Typically, punishments are relatively mild and compensation is weaker than that of the United States (OECD “Governance frameworks,” 2018). Like most other BRICS nations, Brazil lacks the de facto power to successfully enforce any intellectual property rights in the court system (OECD “Governance frameworks,” 2018).

Brazilian enforcement mechanisms against IPR violations have been advancing over the years, starting with the establishment of The National Council to Combat Piracy and Crimes against Intellectual Property (CNCP). This council was created on October 14, 2004 to facilitate the improvement of cooperation among various governmental agencies (OECD “Brazil,” 2018). Coordination involves both private industries and public governance, and strategies for enforcement are outlined in The National Plan for Combating Piracy, which encompasses 99 protocols for engaging from short to long term action plans that are consistently revised for accuracy (“Country Focus,” 2006). The first priority outlined in the plan includes blocking common entrance points that counterfeits enter Brazilian borders by increasing the amount of controls at these identified locations, like the Ponte da Amizade (“Country Focus,” 2006). These strategic enforcement initiatives were successful in increasing the amount of seizures, for example, in 2005, an investigation led to the “seizure of 204 million counterfeited surgical gloves, which contravened health and safety standards” (“Country Focus,” 2006). Additionally, the CNCP is involved in outreach programs and supports industry price issues (“Country Focus,” 2006). For instance, the CNCP has advocated for cheaper alternatives to the original products, in order to give consumers the option to purchase goods at lower prices without turning to the counterfeit market (“Country Focus,” 2006). The CNCP has pushed the industrial sector to develop a coordinated plan to tackle this issue for the benefit of protecting all brands in the industry (“Country Focus,” 2006). Through demonstrating stronger IP protection measures in Brazil, the United States, among others, have indicated an increase in business investments would follow, along with a greater opportunity for group constructed enforcement mechanisms (“Office of the United States,” 2018).

Collaborations within Brazil have been successful in strengthening enforcement as well. In 2013, The National Council to Combat Piracy and Crimes against Intellectual Property teamed up with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) to launch the National Directory to Combat Counterfeiting (OECD “Brazil,” 2018). The directory has become a central database for the concentration of information on counterfeit activities that industries and governmental organizations can access publicly (Tomimaru, 2018). Access to common information promotes the spread of information and cooperation across the various sectors that defend against counterfeit operations (OECD “Brazil,” 2018).

Brazil has been especially interested in amping enforcement efforts at ocean ports since imports of counterfeit products enter the country mainly through sea transport networks at 35% of total imports (OECD “Brazil,” 2018). To aid in the enforcement efforts, brand owners routinely distribute “training courses and manuals to the borders officials about their trademarks, copyright and products” (Tomimaru, 2018). Due to the lack of available resources, border officials may only possess knowledge about these trademark infringements through the information provided by industry officials in how to protect their brands (Tomimaru, 2018). Other enforcement units are employed within Brazil to conduct more detailed application, like those in Rio de Janeiro (“Office of the United,” 2018). These specialized IP police forces are useful in a target region, like Rio de Janeiro, to allow the police units to conduct operations effectively with a smaller scope of focus, instead of focusing on the Brazilian state as a whole.

C: International Cooperation

International cooperation is vital for facilitating informative dialogue and formulating cooperative action on global concerns, such as trademark infringement. Such issues are borderless, and require joint efforts to formulate solutions. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is one international entity that plays a role in orchestrating partnerships among the world’s powers. Established January 1, 1995 during the Uruguay Round of negotiations (1986-94), the World Trade Organization serves as a place where countries can engage in formal discussions and resolve disputes involving trade-related problems that arise (“Understanding,” n.d.). Dealing with trade agreement conflicts, especially solving trade barrier disputes, developing WTO trade agreements, and providing assistance to developing nations through international cooperation, are all core function of the WTO (“WTO: Who we are,” n.d.). The guiding principles to WTO member engagement are comprised of five principles: non-discrimination, transparency, reciprocity, flexibility, and consensus decision making (Baldwin, 2016). A total of 164 countries are members in the WTO, including the United States (est. 1995) and Brazil (est. 1995) (“WTO: Who we are,” n.d.). China became a member on December 11, 2001, after pledging to commit to “open and liberalize its regime to better integrate in the world economy” (Jain, 2014, 185). This was significant due to the fact a communist society was agreeing to neoliberal terms of international trade engagement dictated by free trade (Jain, 2014).

One particularly influential WTO Agreement is the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which was established during the Uruguay Round as a legal framework for conducting trade involving intellectual property (“WTO: Intellectual,” n.d.). These legal obligations were intended to create “more order and predictability, and to settle disputes more systematically” in the global economy (“WTO: Intellectual,” n.d.). The goal was to formulate a base international rule that would aid in establishing a more cohesive way to enforce and protect intellectual property across state actors (“WTO: Intellectual,” n.d.). TRIPS creates a baseline set of agreements, such as an obligation of timely IP violation enforcement, minimum protection standards, as well as “how to settle disputes on intellectual property between members of the WTO” (“WTO: Intellectual,” n.d.). For example, TRIPS Part III Section I Article 1 states:

“Members shall ensure that enforcement procedures as specified in this Part are available under their law so as to permit effective action against any act of infringement of intellectual property rights covered by this Agreement, including expeditious remedies to prevent infringements and remedies which constitute a deterrent to further infringements. These procedures shall be applied in such a manner as to avoid the creation of barriers to legitimate trade and to provide for safeguards against their abuse” (“AGREEMENT ON,” 1994)

By establishing a uniform set of international norms towards intellectual property enforcement, the hope was that an increased awareness and initiative to protect IP rights would foster in the global economy to essentially coordinate on future enforcement mechanisms.

The implementation of the TRIPS Agreement was diversified based upon a country’s level of development. Member countries that are considered “developed” were given until January 1, 1996 to fully apply the TRIPS guidelines, while a “developing” member had until January 1, 2000 or even 2005 (“Office of the United,” 2014). However, the period of transition was further extended in 2013, where select “developing” members now have until July 2021, or unless they reach the “developed” member status (“Office of the United,” 2014). Hence, different member countries are in varied stages of implementation, which can affect the level of effectiveness and uniform responses to IP protection.

The success of the World Trade Organization and TRIPS is best explained by the degree of international awareness and connectedness around IP related issues that has spurred from the creation of these entities. In particular, the lesser developed countries were given a better opportunity to advance IP enforcement in hopes of encouraging a desire for greater local innovation and creative production (Park, 2012). With stronger protection mechanisms in place within the developing countries, it would motivate developed countries to seek investments in regions where there were previously no IP protections, due to greater IP enforcement (Park, 2012).

In particular, the United States has sought an active role during TRIPS council meetings discussing a WTO member country’s status of application in comparison with TRIPS guidelines. The US uses these engagements to “pose questions and seek constructive engagement” on various issues regarding TRIPS application (“Office of the United,” 2018, 35). This demonstrates active participation within the international community by engaging in a forum that promotes cooperation and dialogue.

Another success is the ability of the WTO to incorporate a diverse set of countries towards cooperation in a global manner. The official integration of communist China into an set of international norms focused on free trade, pledges the Chinese government to obliging with additional WTO agreements and rules like the Most-Favored Nation (MFN), which brings global economies together on a wide variety of issues (Blanchard, 2013). It helps ensure that proper action is taken to protect and enforce intellectual property rights through “civil and administrative procedures and remedies, injunctions, and the imposition of compensatory remedies” (Potter, 2007, 705). Particularly in China, due to its pledges in TRIPS, the country has subsequently enacted “national and local legislation and regulations and strengthened central and local institutions for intellectual property rights enforcement” (Potter, 2007, 705-706). TRIPS and the WTO help promote an international set of norms that aid in the continued effort towards collective action.

International cooperation at a progressive enforcement level is conducted through INTERPOL, an international police organization based in Lyon, France (“About INTERPOL,” n.d.). One of the many objectives of INTERPOL is to “identify, disrupt and dismantle transnational organized networks behind the trafficking in illicit goods” (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). To strengthen the enforcement process, the international police has facilitated the creation of a secured police system that aids in the communication, sharing, and analysis of intelligence involving these illicit goods (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). INTERPOL then uses the data collected to execute trafficking operations alongside their numerous partner organizations and enforcement units (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). Operation mechanisms at INTERPOL seek a multidisciplinary approach to the enforcement of intellectual property crime (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). A variation of enforcement includes training programs, such as the IP Crime Investigators College (IIPCIC). Training involves online courses in five key languages targeted at law enforcement, as well as industry professionals, on learning skills to adequately enforce intellectual property crimes (“IP Crime,” n.d.). Outreach programs at INTERPOL embrace social media outlets, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, to spread awareness of the threats associated with illicit trade through the tag “#StopIllicitTrade” (“IP Crime,” n.d.). The enforcement activities of this international police unit are useful to apply a multi-dynamic approach to dealing with intellectual property crimes.

INTERPOL’s success in approaching IP crimes is largely due to its widespread presence across the international community. Along with their headquarters located in France, INTERPOL includes additional bureau located throughout the globe. For instance, INTERPOL Brasilia, INTERPOL Beijing, and INTERPOL Washington were established in 1986, 1961, and 1956 respectively (“Member Countries,” n.d.). Although INTERPOL is a global police force, having individual bureau branches established in other countries reinforce the presence of the agency’s goals and pledges in a more localized way.

The international police force brings regions together in solidarity through engaging in joint operation efforts with target countries. For example, between August 15 to August 31, 2015, Operation Jupiter VII was conducted involving INTERPOL, Brazilian, as well as ten additional Latin American law enforcement forces for the seizure of counterfeit products and their illicit factories (“South American operation,” 2015). The operation was quite successful with the seizure of 800,000 counterfeit products worth around US$130 million, and the detainment of 805 people associated with the criminal network (“South American operation,” 2015). Counterfeit goods seized varied in products; however, it included clothes, cosmetics, electronic parts, construction material, as well as fertilizers (“South American operation,” 2015). After the conclusion of Operation Jupiter VII, the head of INTERPOL Brasilia, Valdecy Urquiza Junior, stated that “the Brazilian Federal Police encourages and supports the efforts of INTERPOL in fighting organized crime through Operation Jupiter” (“South American operation,” 2015). Michael Ellis, the head of INTERPOL’s Trafficking in Illicit Goods and Counterfeiting unit, added that “operations such as Jupiter VII show what can be achieved when law enforcement agencies collaborate against the criminal groups involved in illicit trade” (“South American operation,” 2015). This joint operative displayed joint success among INTERPOL and regional enforcement and is evidence that collaborative international operations can benefit enforcement initiatives in tailored circumstances.

Joint operations have also been conducted with Chinese and US forces. The 2014 operation, known as Genuine Action, involved INTERPOL and the Chinese government, which resulted in counterfeit seizures around US$30 million, along with the arrest of 2,224 criminals (OECD “China,” 2018). INTERPOL conducted a two week operation, codenamed Maya II, jointly with the United States and eighteen South American countries between March 15 and March 31, 2015 (“Fakes worth,” 2015). Counterfeit goods worth around US$60 million were confiscated during Maya II, and its success is credited to steadfast communication among participant countries through INTERPOL sponsored police databases and networks, as well as the WCO’s communication base CENcomm (“Fakes worth,” 2015). Collaborative enforcement operations experience success when paired with engaged participants and technological tools that aid in facilitating communication globally. Without international networks that allow cooperation to flourish, it would prove difficult to gather and advance multinational coordination.

Another success involves specifically the IIPCIC and its training courses. These courses are especially impactful due to their access to the most current IP information that is transferred to industry, government, and law enforcement quickly to deal with such challenges (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). A bonus to these courses is the fact that law enforcement officials can take them for free (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). Allowing law enforcement the ability to learn and develop advanced skills without charge helps facilitate international standards for the global community to act as a collective unit with specified targets in mind (“Trafficking in illicit,” n.d.). Developing more uniform conceptions of intellectual property and the crimes involved brings greater awareness of the severity and damage IP violations produce.

The formation of the World Customs Organization (WCO) has served the role as a platform of exchange for the international community. Membership from the United States, China, and Brazil began in 1970, 1983, and 1981 respectively (“World Customs,” 2018). The WCO helps member countries voice concerns and learn new techniques through collaborative exchanges dealing with trade related issues like counterfeiting. It is a space for member countries to essentially discuss any issues and concerns, which acts as a reinforcement for TRIPS obligations.

In 2000, the WCO created the Customs Enforcement Network (CEN), for the purpose of data collection to aid in intelligence gathering in the community (CEN Suite, n.d.). The CEN targets custom officials by providing accessible communication and enforcement requirements, and around 2,197 officials currently have access to the CEN database (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). Expansions of the CEN include applications such as the National Customs Enforcement Network (nCEN) and Customs Enforcement Network Communication Platform (CENcomm), which were created to further facilitate data sharing techniques (CEN Suite, n.d.). The nCEN is a system aimed to provide “customs administrations with the collection and storage of law-enforcement information on the national level, with the additional capability to exchange this information at the regional and international levels” (CEN Suite, n.d.). This exchange of valuable information is further benefited by CENcomm, which encompasses fast-paced technology in creating a “web-based communication system” where custom officials can securely exchange information in “real time” (CEN Suite, n.d.). By continuing to modernize with developing technology, the WCO demonstrates a strong effort towards facilitating dialogue across customs in working towards the common goal of IP protection.

Another online tool created by the WCO has been the Interface Public-Members (IPM) platform, which was designed in 2011, yet updated and released on September 4, 2015. IPM is an online database that law enforcement officials can access mobily “to search a product simply by scanning the barcode and, when available, verifying a product using security features” (“WCO launches,” 2015). With alert notifications available, officers are able to stay informed at current speeds and it is available for iOS, as well as Android devices (“WCO launches,” 2015). Mobile data access helps provide custom officials contact information, the ability to “upload relevant product details,” data customization, and the ability to stay informed on upcoming events to participate in (“The WCO Tool,” n.d.). The adoption and utilization of technology has aided in increasing the accessibility and ease of communication among enforcers across the globe. Efficient and hand-held devices to identify counterfeit products aids the efficiency of IP enforcement, which may lead to an increase in motivated responses by law enforcement.

Besides constructing communication tools for engagement, the WCO organized The Counterfeiting and Piracy (CAP) Group in 2009, which serves as a mechanism for discussing and exchanging information among customs and law enforcement officials involving various practices to fighting counterfeit and piracy activities (“WCO,” n.d.). The CAP meets biannually and promotes respectable dialogue for all participating members (“WCO” n.d.). Allowing various officials from diverse countries a space to connect and mediate joint issues is crucial to work towards developing common solutions to IP crimes.

Successes involving World Customs Organization activities are widespread and involve various online tools. The CEN has aided in analytical assessment of data in a “user-friendly” way with search functions and automatic uploads so content is currently available for global users (“Customs Enforcement,” n.d.). Easily convertible data aids in allowing officials to process information to make informed and quick decisions that was previously not as easily accessible. A core benefit is that users from across the globe can utilize these resources using modern technology in ways that connect communities for mutual benefits. Especially with the advancement of the IPM platform, including diverse brand involvements, such as automotive, electronics, fashion, and pharmaceutical, the mobile platform has expanded sector-wide (“The WCO Tool,” n.d.). This expansion can also be witnessed through the WCO partnering with an IT service provider Canon Information Systems (Shanghai) Inc., also known as Canon ITS Shanghai. Within Canon ITS Shanghai, a service called “C2V Connected” was developed to help identify fake Canon camera devices through a mobile device that consumers can acquire through an app (“The WCO announces,” 2016). In 2016, “C2V Connected” integrated with the IPM platform to jointly combat counterfeit goods, which ultimately helps broaden the scope of brand protection enforcement (“The WCO announces,” 2016). This merging of technologies and enforcement tactics demonstrates an increased collaborative effort towards IP enforcement, especially involving a country like China, which displays repeated difficulties in enforcement of trademark infringement.

The World Customs Organization has additionally demonstrated success during joint operations with member customs officials. For example, during the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil, the WCO, the European Union (EU), the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), among other organizations, collaborated to intercept thousands of counterfeit football-related products (“Thousands of fake,” 2014). Codenamed Operation Gol 14, it lasted one week during late March, and concluded with the confiscation of 750,000 counterfeit clothing and sport products (“Thousands of fake,” 2014). This operation integrated not only WCO networks, but the EU, as well as regional customs. In particular, Brazilian involvement displays a proactive step towards continuing to strengthen their IP enforcement networks and mechanisms, along with aid from the international community. Overall, due to persistent efforts of technological advancement, and joint partnerships and operations, the World Customs Organization fosters global initiatives to further trademark protection to benefit collective interests.

Section 2: Barriers

Although international cooperation has aided in joint enforcement successes and enhanced the spread of valuable information regarding enforcement mechanisms, barriers exist that hinder such cooperation which allows for the continued flow of counterfeit goods. Countries, like the United States, China, and Brazil, engage in global cooperation mechanisms, along with domestic enforcement, yet coordination is not always feasible nor desired. These barriers involve a cultural element, related to Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory, as well as the consumption culture within China. Issues regarding seriousness of enforcement by the individual countries plays a role in hindering joint cooperation on the international stage as well. Lastly, barriers to technological access, relevance of data, and the resulting costs of using advanced technology place constraints in facilitating inclusive information sharing capacities.

Cultural components affect a country’s policy decisions, as well as those decisions that ordinary citizens make in the community and within the global system. Particular values that a society holds about what is deemed acceptable revolves around ingrained values and societal structures. Geert Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory provides insight into why barriers to international cooperation exist regarding trademark protection. In 1980, Hofstede first published his Cultural Dimensions Theory, which analyzed and collected data from around 116,000 subjects on cultural elements administered in surveys and later categorized into dimensions (Robertson, 2000). The first dimension is called individualism, and Hofstede claims individualism as “the relationship between the individual and the collectivity which prevails in a given society. It is reflected in the way people live together, for example, in nuclear families, or tribes; and it has all kinds of value implications” (Robertson, 2000, 255). If a society is more individualistic, then citizens care more about their own families and their personal wellbeing, rather than society as a whole (Robertson, 2000). Ties with others are deemed more “loose,” while individuals are more focused on their own personal survival (Hofstede, 2001). In complete contrast is collectivism, where society emphasizes “a tight social framework in which people distinguish between in-groups and out-groups” (Robertson, 2000, 255). Within a collectivist society, “strong, cohesive” groups form that protect those people within in return for unwavered loyalty to the societal structure (Hofstede, 2001).

Whether a country is more individualistic or collectivist could be a factor in why certain countries are more engaged in international cooperative efforts. The United States, and more Western societies, demonstrate an individualistic framework with such heavy emphasis on personal freedoms and liberties granted in society. In a “dog-eats-dog” societal system, fighting for advancing trademark protection mechanisms would be logical because an individual brand owner wants what is in his/her best interest, and that would be continued protection of intellectual property. An individual would want to protect his/her personal ideas; hence, a greater engagement in the enforcement of these rights would be ideal. In a collectivist society, such as China, citizens view themselves as a component of the whole; therefore, decisions are rather based on what is in the best interest for the society, not personal self-interests. In other words, “one’s individual beliefs and desires are submerged to fit with the greater good – or what is acceptable in society as a whole” (Wang et Lin, 2009, 402). This adds understanding to why Chinese society is less motivated to report on counterfeit activity. If engaging in counterfeit activity helps provide a source of income and jobs for members of society, then to notify authorities of the illegal activity would end up hurting those workers and cause struggles to provide for a family. With society structured in a group formation, one would choose not to hurt a member of the group because it would end up hurting the group as a whole.

The Cultural Dimensions Theory was expanded in 1988 by Hofstede and Bond to encompass what is called Confucian Dynamism. This new dimension focuses on Asian values related to the Chinese philosopher named Confucius and his value system (Robertson, 2000). Confucian Dynamism produces a scale with societies either receiving a “high score” or “low score” regarding their association and implementation of Confucian values (Robertson, 2000). Societies with high scores of Confucian Dynamism are deemed more “future-minded” and associated with “persistence, ordering relationships by status, thrift, and having a sense of shame” (Robertson, 2000, 256). In direct contrast, a low score means a society tends to focus more on the present circumstances and associated with “personal steadiness and stability, saving face, respect for tradition, and reciprocation of greetings, favors, and gifts” (Robertson, 2000, 257). The study resulted in high Confucian scores for countries in Asia, like China, Korea, and Japan, while low Confucian scores were given to western countries, such as the United States and Canada (Robertson, 2000).

This expansion further clarifies why collectivist societies may be more resistant to enforcing trademark protection by connecting characteristics of society to Chinese Confucian cultural values. Through the association and emphasis of status, society values the production and purchase of counterfeit products more because having a name-brand product is viewed as important in Chinese society. The Chinese consumption value of face consciousness, which is a cultural value that places “emphasis on prestige, recognition, and status,” supports this theory that the “face” of a product demonstrates the desired status in society (Wan et al., 2009, 187). Face is the “reputation achieved from maturing in life, through success and ostentation” (Wang et Lin, 2009, 401). Through owning a counterfeit luxury product, the good displays to the rest of society that the consumer is well-off and of a higher status, which is essentially the end goal of many in Chinese society. Impressing others in society is quite important, for example, some girls will save several months’ salary just to purchase an expensive Louis Vuitton handbag to purely appear wealthy to the masses (Wang et Lin, 2009). By displaying these luxury brands, consumers are able to display their prestige; therefore, counterfeit products are an instrument to meet the goal of reaching high status (Wan et al., 2009). Counterfeits contain the appeal of being luxury and demonstrating personal success. Also obtaining a cheaper good, regardless if it is considered a luxury brand, is viewed as favorable since it costs less than the authentic product.

Along with displaying material wealth, Confucian values also encourage thrift. Thriftiness is considered a core Chinese cultural value (Wang et Lin, 2009). Confucius encouraged frugality, and he was quoted stating that “He who will not economize will have to agonize” (Wang et Lin, 2009, 401). In this way, counterfeit products meet the twin objectives of high status and being thrifty, because the goods are cheap but also seem legitimate to members of society. When Chinese citizens purchase counterfeit goods, it does necessarily seem like such a negative action because these Confucian values encourage choosing actions that are cost efficient, and counterfeit products serve this objective.

Barriers to international coordination and cooperation present themselves through countries’ degree of seriousness on the issue of trademark protection and the resulting enforcement power by these institutions. Among the three case studies, China in particular has displayed the most resistance to complying with TRIPS obligations. Although China may follow WTO guidelines on paper, there is not complete enthusiasm to do so (Toohey et al., 2015). During TRIPS Council meetings, China displays a pattern of siding with the developing world of resisting when presented with expanding the intellectual property rights obligations encompassed within the TRIPS agreement (Toohey et al., 2015). Even though China is a member of TRIPS and technically abides by the policies, the country is not trying to expand upon IPR regulations to improve the enforcement of trademark infringement. This is further demonstrated when China enforces these policies, and they do so in narrowly confined terms (Toohey et al., 2015). China represents a commitment to enforcement, but there is a lack of strong initiative to continuously improve IP protection. TRIPS Article 61 states that:

“Members shall provide for criminal procedures and penalties to be applied at least in cases of wilful trademark counterfeiting or copyright piracy on a commercial scale. Remedies available shall include imprisonment and/or monetary fines sufficient to provide a deterrent, consistently with the level of penalties applied for crimes of a corresponding gravity” (Berman & Mavroidis, 2007, 68-60).

The issue is that China has failed to apply such penalties as effective deterrent. For international cooperation to enhance and further integrate towards the collective goal of trademark protection, participating the bare minimum is not going to produce the most impactful action. There are beliefs that the Chinese Communist Party is powerless to enforce trademark infringement in that the “mountains are high and the emperor is far away” (Mercurio, 2012, 26). With this mentality present in Chinese society, it gives the impression to counterfeiters that IPR violations are not only difficult for the CCP to enforce, but that they are not committed to enforcing them either.

Upon these allegations, China has defended its involvement, claiming they are no different in enforcement than any other member of TRIPS (Toohey et al., 2015). However, these conflicts of degree of enforcement only adds tension among members and further divide among cooperative action. Rather than working towards improving IP regulation, these countries are challenging each other over how seriously they are taking international obligations. Chinese objections to these allegations are not entirely wrong, especially when taking in account the transition period granted to developing country members of the WTO. By January of 1996, all developing countries were supposed to have fully implemented all TRIPS obligations; however, some countries were first given an extension in 2000, and select countries are still currently in the process of administering effective IP legislation (“Office of the United,” 2018). This proves that although countries are members of institutions that administer and advocate for IP regulations, it does not mean that all countries involved are actively engaged in the promotion of such change and advancement. For institutions like the WCO, active participation in a “member-driven organization” to connect and talk about future improvements of policies are imperative to keep the whole institution afloat (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). Although member countries of TRIPS may challenge the enforcement of Chinese trademark violations, China’s efforts towards expanding their IP courts have not gone unnoticed; however, compared to other members, it is not as modern nor as impactful.

Other institutions, like INTERPOL, also rely on partnerships with national government agencies to work efficiently. For joint operations to work effectively, there needs to be a level of cooperation among participating nations. If these ties are fragmented, it can be difficult for countries to rely on each other to adequately enforce IP violations. Joint operations already face difficulties with having a short time span of a few weeks to months to operate; hence, without solid relations, enforcement is unable to consistently improve.

Lastly, barriers to international cooperation and coordination are partly a result of the inability of participating parties to access technological enforcement mechanisms, issues with relevance of data obtained through technology, as well as the inability to afford advancing technology. In the World Customs Organization, this barrier is demonstrated through the ability for custom officers to utilize the CEN database (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). The CEN database requires internet connection; therefore, if customs in a country do not have strong internet access, the database would fail to be a tool that officials could reliably use. Additionally, not all officers are trained to use the database correctly, which makes the CEN database even less impactful as a tool for trademark enforcement. Studies have shown that there is a gap in technological access and knowledge in lesser developed countries versus those in the developed world, where internet access is more widespread and officers more knowledgeable on the database (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). With officers in the defined developed world, like the United States, data collection has been viewed as a resource for predominantly statistical analysis (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). The issue with this conclusion is that if the developed world is just utilizing the database, significant sources of data are therefore missed in future analysis to determine the best enforcement mechanisms. Places like Brazil, that may have lesser access to reliable internet connection, will neither have the platform to display the country’s trademark difficulties nor connect with the international and local communities involving impactful enforcement mechanisms employed by other institutions.

Relevance of data has also emerged involving the technological databases, such as the CEN database and its ability to adequately inform customs officials. In a study conducted involving countries familiar with the WCO networks, in particular the CEN database, 23 countries were emailed a survey to their National Contact Points (NCPs) involving a series of questions about the utilization, strengths, and weaknesses of the WCO tool (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017). Results from the survey outlined that the most significant issue is that “the data are too old, incomplete or inconsistent, and do not reflect the current global situation” (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017, 41). If data uploaded is not consistent with modern times, it is difficult for government officials to make fully informed decisions on the best ways to tackle enforcement issues. It becomes difficult for actors in the international system to coordinate effectively if certain parties do not have access to the most up-to-date information. Timely uploading data is crucial with the advancement of new findings to correctly guide other countries on the most recent developments in trademark protection.

Issues with the exchange of relevant information is further displayed through the survey response stating that “only three countries use the CEN database for analytical purposes, [while] fifty per cent of the countries use the database for entering seizure messages only, and they do not use it to make any kind of query or analysis” (Czyżowicz & Rybaczyk, 2017, 42). The CEN database is designed to facilitate an exchange and analysis of current data trends for custom officials, yet half of the countries surveyed do not fully capitalize on the tool. If countries are not actively engaged in the utilization of the CEN database for finding analysis and are only uploading their findings into the web-based tool, it fails to facilitate the dialogue and spark constructive change that it was intended to coordinate for the international community. Not only is global dialogue less impactful, but if the quality of data is also not current, the result is a tool that the international community may deem unsuitable or irrelevant for their future engagements and may slowly utilize less regularly over time.

Advancing technology to reach and facilitate cooperation in the international community is not used free of charge. The resulting fees to acquire access to technology that aids in global trademark enforcement can exclude certain countries from collaborating on joint international initiatives. Lesser developed countries may not have the funds available to afford technological fees; however, they may still have serious IP violation problems that could benefit from such access. For example, the utilization of the IPM mobile platform facilitated by the WCO requires varying levels of fees for a country to acquire access. The range for a IPM mobile contract begins with €480 per year with access for one brand and one user, to premium access of €6,500 per year with an unlimited number of brands and users allowed to participate on the contract (“The WCO Tool,” n.d.). The more a country is willing to spend on the platform, the greater access the government will have to the ability to upload products, a greater number of contacts accessible, as well as IPM online tool training capabilities (“The WCO Tool,” n.d.). If a country is only able to afford the most basic contract, it excludes the country from engaging in the entirety of the platform and bars them from access to product upload, which is a key component to keeping consistent with current product counterfeit identification concerns. This essentially creates a system of inequality in the ability to keep up with evolving international cooperation tools, with mainly developed and wealthy countries able to engage while the lesser developed and poor countries are kept out of the loop of information. International cooperation needs to allow more equal access to allow for group coordination efforts to effectively occur. Trademark infringement problems are not exclusively in the developed world; hence, poorer countries have knowledge and their own issues that would add to developing effective policies to hinder counterfeit activities.

Section 3: Future Predictions & Recommendations

The future of international trademark enforcement displays movements towards positive, impactful change, yet barriers continue to place restrictions on globally designed mechanisms. China’s role in the international community is one that influences the fate of trademark enforcement in the foreseeable future. Continuing since 2013, the prominence of China has failed to falter as the leading source of counterfeit goods; however, the country rises as a player in the enforcement of the criminal activity. The future of Chinese IP involvement looks promising, although Chinese Confucian cultural value belief system remains strong and prevalent, an emergence of western influence is difficult to ignore.

The opening of Chinese markets since the 1970s has introduced Chinese society to western norms of individualism; hence, traditional Confucian values are becoming challenged by competing viewpoints to consumption (Tang & Koveos, 2008). This brings support for the Chinese officials’ argument that China is indeed respecting the agreements signed within its member international organizations like the WTO and TRIPS. Due to the introduction of open-market mechanisms into the Chinese economy, society is given the opportunity to accommodate international norms to aid in the global enforcement of trademark protection. If more western-style consumption culture and individualism begins to trump over traditional Chinese collectivist values, it could transform Chinese society into further accepting laws protecting intellectual property if such values become worthy of adherence. The rise of the Chinese business sector is a way for change to occur from within; through methods of globalization, where universal IP values slowly become more ingrained into Chinese culture through consistent global trade relations. These IP values do not necessarily need to mirror Western IP values, but incorporate ways to provide advancing measures for brand security. This transformation in consumption culture would be rather slow, yet an impactful transition would take time and require an increased effort and engagement by the CCP. Participation in international agreements and enforcement mechanisms like the WTO, TRIPS, INTERPOL, and WCO help promote protection of IP rights, and are ways for influencing Chinese actions and enforcement towards these crimes.

The Kahle (1983) social adaptation theory states that “values are a type of social cognition that functions to facilitate adaptation to one’s environment through continuous assimilation, accommodation, organization, and integration of environmental information” (Wang & Lin, 2009, 404). For China and trademark protection, involvement in international cooperation mechanisms is the environment that can help assimilate Chinese values to become more cohesive with the international community. The process of social adaptation requires a degree of integration, and China has displayed this action through agreeing to liberalize and open its economy to greater levels (Jain, 2014). Positive reinforcement changes are also seen domestically within China through the CCPs’ pressure on e-commerce mechanisms, such as Alibaba, to increase the supervision of counterfeit products distributed through the website (“The world’s factory,” 2018). The prevailing issue is whether or not China will continue to place pressure on these infringement platforms or rather it is just for show. If greater protection is granted to trademarks in China, it would benefit brand owners in facilitating greater trust engaging in the Chinese economy; hence, helping the Chinese economy flourish as well. Also, the presence of mass media could aid in the promotion of more western IP protection values in addition to formal international institutions (Wang & Lin, 2009). Media outreach could aid in spreading awareness and encouraging greater cooperation of enforcement in places like the United States and Brazil with freer internet access; however, media would be less impactful in China due to the CCP’s severe internet restrictions.

The degree to which enforcement cooperation is taken seriously among member countries will continue to affect the level of success that joint coordination efforts will produce. With certain developing countries still in the process of implementing WTO agreement mechanisms (“Office of the United,” 2018), it does not created a cohesive unit of enforcement. An expansion of IP protection is a global concern, but if not all members are completely and actively participating to the full extent, it may be difficult to rely on these members of the international community. In the case of Brazil, anti-counterfeit operations have failed to reach a desired level of impact. By lacking strong state-sponsored enforcement mechanisms, it proves difficult for Brazil to adequately record and manage counterfeit activity within its borders. Joint operations are a way to help combat this problem for Brazil by utilizing the resources of neighboring countries and international organizations. With a disconnection between border officials and brandowners about product identification, it proves difficult to adequately enforce the borders for counterfeit goods entering the country. Successful joint operations regionally and internationally have been a positive way to continue enforcement and opportunities for government enforcement officials to learn new tactics. Brazil should strive to continue these global interactions, to demonstrate to the international community that Brazil is making efforts towards improving and protecting IP rights. This would additionally help Brazilian economy since the US has acknowledged that if Brazil improves enforcement, US businesses will invest more in the country (“Office of the United States,” 2018).

Regarding technological complications, international cooperation and coordination would further grow if countries were more actively engaged in the platforms, such as the CEN database and the IPM mobile app. The assessment that data is neither current or adequately analyzed by custom officials demonstrates that flaws must exist in the connection between government officials and the databases. To overcome this issue, these engagement platforms need to determine ways to encourage a greater participation from its WCO members for facilitating data that helps the greater global society. Another issue that must be addressed is the costs associated with the utilization of the technology platforms, like for the IPM Mobile app (“The WCO Tool,” n.d.). For effective international cooperation to occur, lesser developed countries need more equitable access to trademark enforcement mechanisms. By placing a cost on participation, the WCO is essentially placing barriers on the inclusion of poorer countries. This exclusion is troublesome because some of the lesser developed countries, like Brazil, do not have the capabilities to invest in more trademark protection; therefore, they are missing out on tools shared by the rest of the international community. As technology is improving and becoming more prominent for enforcement, there is a need to acknowledge the resource limitations and find ways to increase inclusion within enforcement to facilitate even greater cooperation.

Overall, international cooperation towards trademark protection strives towards creating mechanisms of unity within the global community; however, barriers exist that must be continuously challenged in order for universal intellectual property enforcement to become more impactful. No single country nor organization has the capability to enforce and prevent the flow of counterfeit goods in the market alone. The unification of domestic and international efforts, as well as the homogeneity of enforcement tactics and combination of resources can aid towards producing the force required to elevate the success of trademark protection in the global market.

2019 Copyright Michigan State University Board of Trustees.

References

About INTERPOL Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.interpol.int/About-INTERPOL/Overview

AGREEMENT ON TRADE-RELATED ASPECTS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

RIGHTS, Annex 1C of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Apr.15, 1994. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_01_e.htm

Baldwin, R. (2016). The World Trade Organization and the Future of Multilateralism. The

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(1), 95-116. DOI:10.1257/jep.30.1.95

Berman, G.A., & Mavroidis, P.C. (Eds.). (2007). WTO Law and Developing Countries. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Blanchard, J.F. (2013). The Dynamics of China’s Accession to the WTO: Counting Sense,

Coalitions and Constructs. Asian Journal of Social Science, 41(3/4), 263-286. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23654844

CBP and the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (TFTEA). (2018, July 30).

Retrieved from https://www.cbp.gov/trade/trade-enforcement/tftea

CEN Suite. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/instruments-and-tools/cen-suite.aspx

Chikada, A., & Gupta, A. (2017). Online brand protection. In P. E. Chaudhry (Eds.), Handbook

of Research on Counterfeiting and Illicit Trade (pp. 340-365). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

China: E-Commerce Law Passed. (2018, November 22). Retrieved from

https://advance-lexis-com.proxy2.cl.msu.edu

Country Focus – Combating Piracy: Brazil Fights Back. (2006). WIPO Magazine, 5.

https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2006/05/article_0003.html

Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China. (1997). Retrieved from

https://www.cecc.gov/resources/legal-provisions/criminal-law-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china

Customs Enforcement Network (CEN). (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/instruments-and-tools/cen-suite/cen.aspx

Czyżowicz, W., & Rybaczyk, M. (2017). Customs Enforcement Network (CEN) database

perspective: A case study. World Customs Journal, 11(1), 35-46. Retrieved from http://worldcustomsjournal.org/Archives/Volume%2011%2C%20Number%201%20(Mar%202017)/1827%2001%20WCJ%20v11n1%20Czyżowicz%20and%20Rybaczyk%20.pdf

Fakes worth USD 60 million seized in operations across Americas and Caribbean. (2015, June

1). Retrieved from https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2015/Fakes-worth-USD-60-million-seized-in-operations-across-Americas-and-Caribbean

Fekete, E.K., Leonardos, G., & Advogados, K.L. (2018). Trade mark litigation in Brazil:

overview. Retrieved from https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-011-2481?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true&comp=pluk&bhcp=1

Hiney, J., & Mottes, L.M. (2017). United States. In J. Wild (Eds.), World Trademark Review

Yearbook 2017/2018 (pp. 245-251). London, UK: Globe Business Media Group.

IP Crime Investigators College. (n.d.). Retrieved from

Jain, R. (2014). China: Enmeshed in or Escaping the WTO? American Journal of Chinese

Studies, 21(2), 185-204. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44289322

Law on Industrial Property, Law No. 9.279 (1996). Retrieved from

https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/text/125397

Leonardos, K. (2016). Brazil. In J. Wild (Eds.), Anti-Counterfeiting 2016 – A Global

Guide (pp. 119-123). London, UK: Globe Business Media Group.

Member Countries: World. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.interpol.int/Member-countries/World

Mercurio, B. (2012). The Protection and Enforcement of Intellectual Property in China since

Accession to the WTO: Progress and Retreat. China Perspectives, 1(89), 23-28. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24055441

OECD. (2018). Governance frameworks for combatting counterfeiting in Brazil. In Governance

Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade (pp. 157-169). Paris, FR: OECD Publishing. DOI: https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1787/9789264291652-8-en

OECD. (2018). Governance frameworks for combatting Counterfeiting in BRICS Economies:

Overview. In Governance Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade (pp. 141-155). Paris, FR: OECD Publishing. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264291652-7-en

OECD. (2018). Governance frameworks for combatting counterfeiting in China. In Governance

Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade (pp. 171-190). Paris, FR: OECD Publishing. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264291652-9-en

OECD. (2018). Governance Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade. Paris, FR: OECD Publishing.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. (2014). 2014 Special 301 Report, 1-63.

Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/USTR%202014%20Special%20301%20Report%20to%20Congress%20FINAL.pdf

Office of the United States Trade Representative. (2018). 2018 Special 301 Report, 1-86.

Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/Reports/2018%20Special%20301.pdf

Park, W.G. (2012). North-South models of intellectual property rights: an empirical critique.

Review of World Economics, 148(1), 151-180. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41485790

Plane, D., & Livingston, S. (2016). China. In J. Wild (Eds.), Anti-Counterfeiting 2016 – A Global

Guide (pp. 133-139). London, UK: Globe Business Media Group.

Potter, P.B. (2007). China and the International Legal System: Challenges of Participation. The

China Quarterly, 191, 699-715. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20192815

Robertson, C.J. (2000). The Global Dispersion of Chinese Values: A Three-Country Study of

Confucian Dynamism. MIR: Management International Review, 40(3), 253-268. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40835890

South American operation targets crime networks behind fake goods. (2015, September 21).

Retrieved from https://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2015/N2015-137

State Intellectual Property Office of the P.R.C Patent Statistics Annual Report 2013.

(2013). National Intellectual Property Administration, PRC. Retrieved from http://www.cnipa.gov.cn/tjxx/jianbao/year2013/h/h5.html

State Intellectual Property Office of the P.R.C Patent Statistics Annual Report 2016. (2016).

National Intellectual Property Administration, PRC, 1-205. Retrieved from http://www.sipo.gov.cn/tjxx/index.htm

Tang, L., & Koveos, P.E. (2008). A Framework to Update Hofstede’s Cultural Value Indices:

Economic Dynamics and Institutional Stability. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6), 1045-1063. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/25483321

The Global Intellectual Property Academy. (2017, August 28). Retrieved from

https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/global-intellectual-property-academy

The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). (2017). IP Commission Report. Retrieved from

http://ipcommission.org/report/IP_Commission_Report_Update_2017.pdf

The Services of INPI. (2018, February 15). Retrieved from http://www.inpi.gov.br/english

The world’s factory of counterfeit goods. (2018). WIPR Review May/June 2018, 22-25. London,

UK: Newton Media Limited.

The WCO announces that “C2V Connected” of Canon Information Systems (Shanghai) Inc. is

now IPM Connected. (2016, July 8). Retrieved from http://www.wcoipm.org/news/the-wco-announces-that-canonis-shanghai-is-now-ipm-connected/

The WCO Tool In The Fight Against Counterfeiting. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.wcoipm.org/__resources/userfiles/file/IPM-Brochure.pdf

Thousands of fake sporting goods intercepted ahead of 2014 World Cup. (2014, June 10).

Retrieved from http://www.wcoomd.org/en/media/newsroom/2014/june/thousands-of-fake-sporting-goods-intercepted-ahead-of-2014-world-cup.aspx