Clifford Grammich and Jeremy Wilson, 2016

Applying Academic Research Against Product Counterfeiting

Though firms have battled product counterfeiting for years, they continue to encounter many of the same questions. “Why does counterfeiting keep coming back?” asked a vice president of anti-counterfeiting operations. “What are the cutting-edge solutions that are out there? I don’t have time to read and look at everything that’s going on, and I don’t have that skill set. Academia has that skill set.”

Since 2009, the Center for Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection (A-CAPP) at Michigan State University (MSU) has sought to apply its skills to the fight against product counterfeiting. The 2015 Brand Protection Strategy Summit—hosted by the A-CAPP Center in partnership with Underwriters Laboratories, the Kellogg Company, L Brands, Inc., and Dolby Laboratories, Inc.—provided an opportunity to take stock of what academia and industry can learn, and have learned, from each other.

The roughly 75 participants from industry and academia invited to the summit discussed topics as diverse as economic risk in illegitimate supply chains, brand protection in China, benchmarking for brand protection, innovative analytics, and legal issues. The result, a senior director of brand protection claimed, showed that a “mixture of practitioners and academics can be a good thing.”

Methods to Measure Product Counterfeiting

The “unique contribution” of academia to product counterfeiting, said an MSU professor, “is the focus on research and analysis. And we need data and rich information to do that.” Unfortunately, he noted, firms and law-enforcement agencies may, understandably, be reluctant to grant such access. Several recent research efforts, however, may offer lessons that can be widely disseminated in the fight against product counterfeiting.

MSU has pioneered the use of open-source methods for assessing incidents of product counterfeiting. One such effort in the A-CAPP Center has examined counterfeit- pharmaceutical incidents, including the changing sources of these products. Using open sources compiled from media reports, court documents, and other publicly available sources, another MSU professor told the summit, can help researchers “build social context around these acts,” as well as “social cues that are missed in other data,” allowing researchers to “get a better picture of who these individuals are.”

One of the noteworthy differences in the counterfeit-pharmaceutical schemes was between perpetrators who had contact with their victims and those who did not. These groups had differentiating behaviors as well. “Medical professionals were selectively using counterfeit pharmaceuticals,” the professor said. “In some cases, they would give counterfeits; in others, they wouldn’t. This was particularly the case for luxury or designer drugs . . . those things that were most profitable.” MSU researchers also traced changes in sources for counterfeit pharmaceuticals, including increased domestic production of counterfeit pharmaceuticals and other supply-chain changes that will require different enforcement approaches. Many elements of the counterfeit-pharmaceutical supply chain, for example, are legitimate distributors with ties to counterfeiting, mixing supply chains of legitimate and illegitimate goods.

More generally, the professor said, such research points to the “need to revisit the term counterfeit. It’s more of an umbrella term that covers a vast range of activities, a vast range of individuals. Is the person that operates a legitimate retail establishment that buys counterfeit Viagra and sells counterfeit cigarettes across the counter the same as the person that facilitates the movement of counterfeit goods? By using that term, we likely obscure much of the important variation in motivation.”

Public information can also yield insight on differing roles in counterfeiting networks. Using information form an incident database and an indictment of 18 individuals charged with operating a pharmaceutical-counterfeiting scheme, the A-CAPP Center has been able to identify a network of 84 individuals who were involved, including their roles in the scheme.

“We look at relationships, between different units of analysis, between individuals, between businesses, between organizations, between concepts or ideas,” said an MSU professor. One way of examining who is important is to look at those who have the most connections and the most strategic connections.” Many of the most common roles in product- counterfeiting schemes, he said, were wholesalers or middle-men.

“The ultimate goal here,” he added, “is to learn more about how the networks operate, and use this evidence to build strategies both to intervene and to prevent them from forming.”

Such approaches can also pay more immediate returns. An anti-counterfeit and risk-management director noted the network research was “able to take a lot of the criminal-justice mindset and look at all these sellers in these different regions . . . and identify [the key actors] that do it all.” Such work, he added, can provide a very large return on investment in research.

Advancing Brand Protection Practices

Firms themselves, of course, already pursue many brand-protection practices. Results of an A-CAPP Center study, supported by the DuPont Company, of ten firms and presented to the summit indicated that common tactics in brand protection can be both external (e.g., seizures, trademark registration, and legal actions) and internal (e.g., customs training, targeted ng investigations, and market monitoring). Common measures that brand owners use to assess the effects of product counterfeiting include those focusing on brand image, equity, and reputation, while specific metrics may differ by industry.

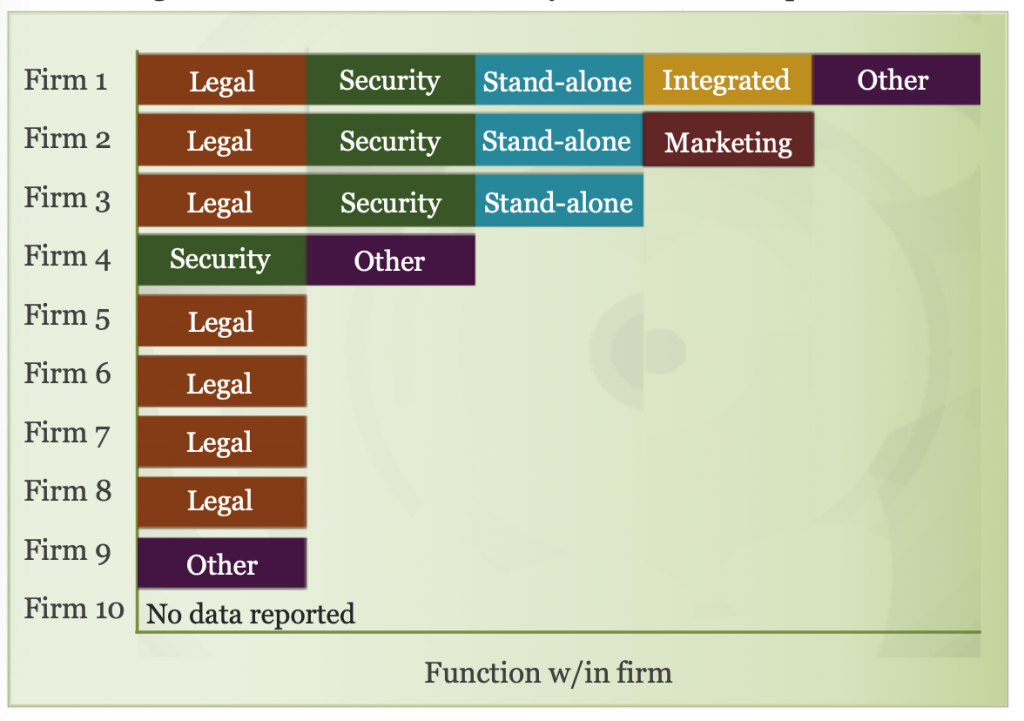

Figure 1.

Positioning of Brand-Protection Teams by Function in Sample of Ten Firms

Firms also recognize the need for multi-pronged approaches to product counterfeiting. While most firms in the study place their brand- protection team within their firm’s legal function, several also have it overlap other functions (Figure 1). Successful brand- protection programs, or at least those perceived to be by respondents, appear to be both aggressive in their brand-protection efforts and proactive in their brand-protection teams. Four successful programs, including one “very” successful program, report being both “aggressive” and “proactive,” while the one program claiming not to have succeeded is “reactive” in its efforts, and another claiming to be unsuccessful is both “very passive” and “very reactive.

This research, a vice president of global brand protection for another firm said, provides an ideal example of academic and industry collaboration, with academic researchers answering a question arising from industry need. It also, he said, presents “the opportunity for us to build a better case [and] to build better programs.”

Communicating the Value of Brand Protection

Brand-protection professionals can face multiple challenges in communicating the value of their efforts, including internally within their companies. A senior manager of intellectual- property protection and enforcement noted that having activities with greatly differing immediate returns for the firm can diminish support for problems with less immediate return but underlying several other problems. Audits of suppliers, for example, typically yield recoveries for the firm of about ten times what are spent on them, he said. This, he explained, can lead to “management perceiving the market isn’t as important as the audits and internal reviews of our partners. [But] we believe it’s very important to see the market. That’s where the actual risks are, that’s where you’re going to find new things” such as copying of programs and infringement of intellectual property.

A chief security officer for another firm suggested that brand-protection professionals may be able to demonstrate the value of their work through more intangible efforts such as a “forward-look risk assessment.” Such an assessment, he said, can help his company when entering a new market to understand its “counterfeit and brand-protection issues. There’s probably a lot of numbers out there[, but the risk assessment] opens to more of a dialogue that we need to be on the front end of going in.”

Within corporations, education efforts on brand protection should focus on globally-relevant content marketed to specific audience needs, said a corporate-outreach specialist. Similarly, application of ideas, principles, or experiences of others can.

“ACAPP is the perfect place to start talking about” these issues, said the senior manager of intellectual-property protection and enforcement. For example, “how are we going to measure ROI [return on investment in anti-counterfeiting activities]? If we could have altogether the same ROI measurements that would definitely change the way you’re perceived, even within your own organization. It’s one thing to say ROI is measured this way versus saying, well, actually, we’re working with academia, where we’re actually developing metrics that are used across the board” by other brand owners as well.

Leveraging Public Partnerships

Communication is also a challenge for public officials responsible for anti-counterfeiting efforts. “Tap 100 people on the back and say, ‘what does counterfeiting mean to you?’” said a director of an intellectual-property rights protection agency. “Over 90 percent of them are going to say the luxury good items, the NFL stuff. Nobody is going to say counterfeit airbags. No one is going to say counterfeit medicine. Because they don’t know.”

Such education efforts need to go beyond the public, he said. “There is no bite, at least in the federal system, in the sentencing,” for product-counterfeiting crimes, he added. The current documentation for sentencing recommendations, he said, is “all numbers, loss of revenue, all economic. [I asked,] did you talk about people dying? Did you talk about people getting sick? They didn’t know.”

Public partners can be very helpful if made aware of problems, a former global-security director said. “U.S. Customs is particularly responsive to brand owners that make themselves known in person at the ports and ask for help,” he said. Customs is very interested in having personal contacts that will be responsive to import problems,” but, he added, “building relationships is necessary before a partnership can be successful [.Y]ou can’t wait until you have a problem to start developing relationships.”

Building awareness and leveraging partnerships can yield results, said the director of the intellectual-property rights protection agency, citing the shutdown of a U.S. manufacturer of counterfeit personal-care products. “If it weren’t for the astuteness of a fire marshal who went into this manufacturing plant and noticed something was astray and notified the local police, they’d probably still be producing these items,” he said. “We worked very well with [brand owners,] and, with the help of the FBI as well as [local law-enforcement agencies], we were able to shut that down in the course of a couple of weeks.”

Standardizing Enforcement Efforts

Partnerships are likely to be critical in addressing emerging issues in the field. For example, while all 50 states (and the District of Columbia) currently have some type of anti-counterfeiting legislation, “these laws vary substantially across states, particularly in terms of the scope and severity of criminal sanctions available to address counterfeiting,” an MSU professor said. Research on these, as well as efforts to benchmark state efforts, can help law enforcement better “understand the strengths and weaknesses of statutes.”

Another MSU project is examining counterfeit products such as shoes, hats, purses, and other apparel identified during tobacco inspections of small businesses by the Michigan State Police. This research will explore how these products and their characteristics can inform future enforcement efforts.

Abroad, several participants noted that issues involving China are likely to continue to be of concern, though improvements are emerging there. A senior director of brand protection recalled, “when we did our first raid in China, we had to sit in a car down the street. We couldn’t even see it. They went in, they raided stuff [but] they didn’t seize any of the computers of any of the stuff that showed who they were buying from or who they were selling to. But in the last twelve years, China has come so far.” He added that many of the issues identified in China are likely to emerge in other nations in future years. A vice president of anti-counterfeiting operations agreed, but said much remains to be done to identify the best enforcement actions in China.

The Future of Brand Protection

Research on other related topics is rapidly emerging. Results of an MSU analysis presented at the summit indicated three times as many articles on product counterfeiting published in the last decade as in the previous two. Nearly half of these appeared in the United States, but such research has appeared in several other nations as well.

Altogether, product counterfeiting is a rapidly growing problem, with responses to it evolving rapidly as well. MSU research supported by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) and presented at the summit indicated several broad issues of concern to academic researchers and brand-protection professionals in coming years—but these often did not overlap.

For example, industry representatives participating at a 2015 UL conference or asked to otherwise comment on emerging issues identified education and awareness, supply-chain security, technology, and consumer focus as among their top issues of concern. Law-enforcement officials concurred in some of these, but were more likely to note the importance of partnerships, an area of lesser concern to other participants. Academic researchers emphasized the importance of analysis and information sharing, an area of lesser concern to others. No academics noted increasing importance of education and awareness, areas where presumably their contribution may be greatest. Service providers were more likely to focus on the growing importance of technology than any other data.

These issues, a senior manager for enterprise risk management and global security told the summit, will likely continue to evolve. “I think we in industry are going to drive what counterfeiting or anti-counterfeiting and product protection is going to look like because it’s our technology. And, as we evolve, so will the counterfeiters,” he said. “Is counterfeiting going to change, or are we going to change the counterfeiters?”

Opportunities and challenges posed by the internet are likely to continue emerging. An MSU professor said discussions among brand owners highlight “how the Internet is a two-edged sword. So companies need to [understand] there’s an incredible vulnerability there. And lots of counterfeits are being sold on the Internet.” Some brand owners claim the Internet will be “the single largest element of activities against brands by 2020.” At the same time, several brand owners note the opportunity the Internet offers to monitor illegal activities—and to identify markets for their brands that they had not known.

The “digital supply chain,” a director of brand protection technology noted, can, “if not managed right, become our worst enemy,” particularly if firms are lax in precautions when sharing prototypes for marketing. At the same time, he added, the Internet can help greatly in education and awareness. “If you’re a patient,” he said, “what’s the first thing you do? You go online and start researching, what did that doctor just tell me? So we’re looking more to integrate into those experiences.”

A former director of brand protection similarly observed, the Internet is “where we live, that’s where the consumer lives, that’s where the counterfeiter lives. And the threats [there] are real, fast-moving and difficult.” One such threat, she noted, was from counterfeiters who often constructed websites to direct complaints about their goods to the legitimate brand website. To advance industry responses to such threats, she contended, institutions like the A-CAPP Center can serve as a trusted broker in sharing information. “This is where MSU is really a great partner,” she said. “As brand owners, we have an academic institution that can take our information and help us filter through it and help us with our strategies.”

2016 Copyright Michigan State University Board of Trustees.