Jay Kennedy, 2019

PREFACE

This report is a detailed review of product counterfeiting incidents contained within the A-CAPP Center’s Product Counterfeiting Database (PCD), most of which involve pharmaceuticals, electronics, food products, and automotive parts. The PCD contains information about specific product counterfeiting schemes, including information about the offenders who were criminally indicted. Cases contained within the PCD include schemes that were detected between the years 2000 and 2015. This report focuses upon concurrent or convergent crimes– that is to say those crimes that occur alongside counterfeiting offenses. The illicit acts involved in product counterfeiting do not occur within a unique criminal vacuum, and product counterfeiting schemes require interactions with legitimate entities. Additionally, most counterfeiters can be thought of as generalists who also engage in non-counterfeiting criminal schemes.

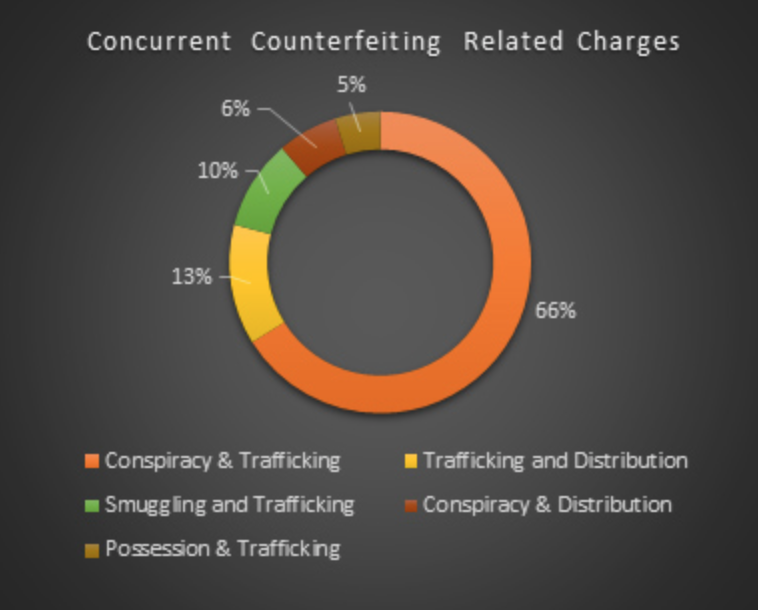

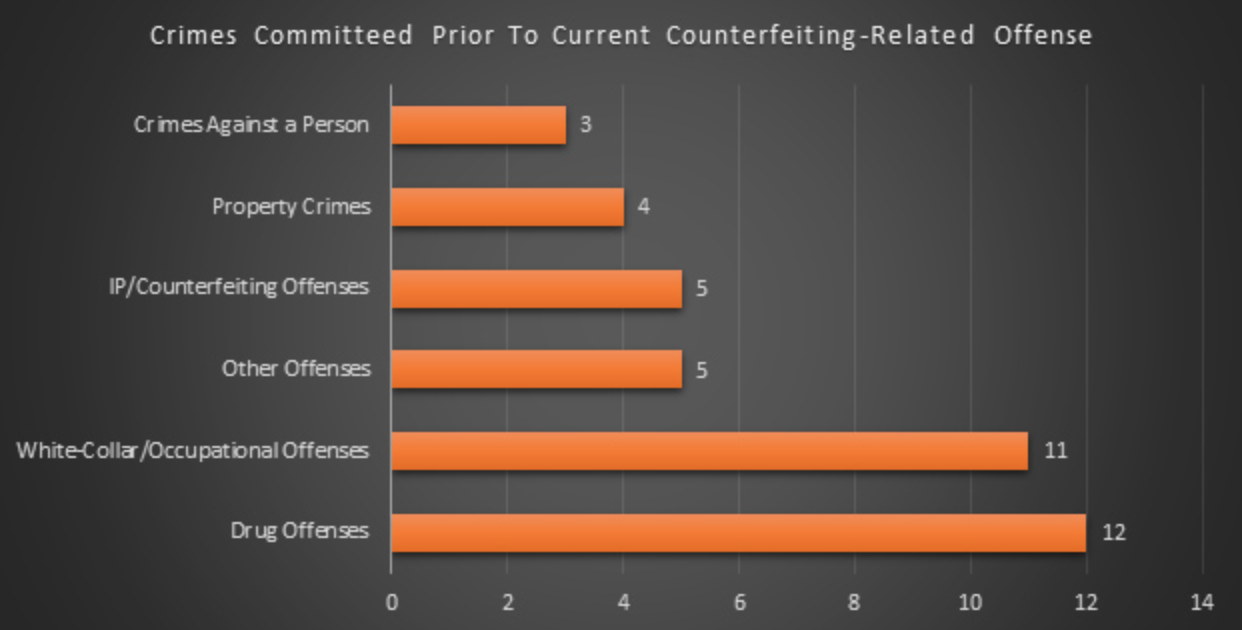

We found that just over 20% of individuals are charged with multiple counterfeiting-related crimes, with conspiracy and trafficking in counterfeit goods being the most frequent combination of counterfeiting charges. We also found that 13.2% of individuals charged were the owner or co-owner of a legitimate business, and evidence exists that the individuals used their businesses to facilitate parts of the scheme. Additionally, 11.3% of charged individuals were licensed healthcare providers. Just over 5% of individuals charged had prior convictions for some other crime, with 30% of individuals with prior criminal histories being charged with a drug-related crime. Another 27.5% had a history of fraud, white-collar crime, or occupational offending, 12.5% had a prior history of intellectual property crimes or counterfeiting, 10% had a prior history of property crimes, and 7.5% had committed a crime against a person.

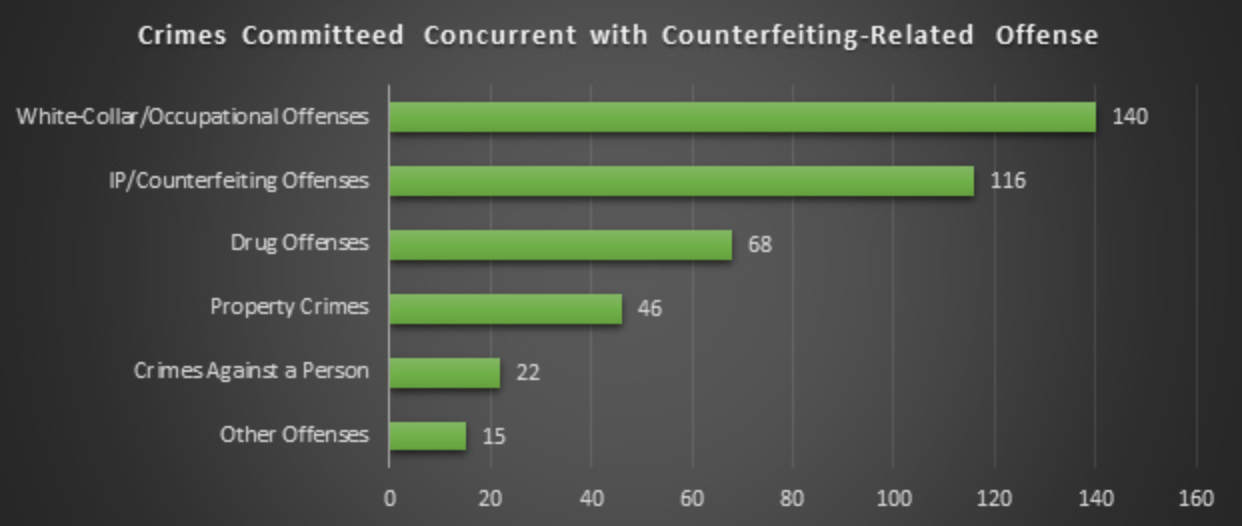

The most commonly charged concurrent crimes were white-collar and occupational offenses (34.4%), including money laundering, tax evasion, and fraud. Intellectual property and counterfeiting offenses were the next most common concurrent charges (28.7%), including the sale of counterfeit goods other than those charged in the primary case, software piracy and copyright infringement. Concurrent drug offenses (16.7%) primarily consisted of illegal drug trafficking, while concurrent property crimes consisted almost exclusively of trafficking in stolen goods. There were a number of serious crimes against persons charged concurrently, including assault with a deadly weapon and attempted homicide.

More worrisome were the five individuals with identified links to terrorist activities. While these individuals represent less than 1% of all the individuals in our database, their activities have the potential to have far reaching consequences. In addition to counterfeiting, these individuals were concurrently charged with providing material support (weapons) for terrorism, and the financing of terrorism and terrorist organizations.

Despite its outward appearance, product counterfeiting is far from being a stand-alone crime, and the large financial returns to be gained likely attract a host of illicit actors. The convergent nature of the criminal schemes described in this report suggest much about ways to mitigate counterfeiting opportunities. First, it is important to think about counterfeiting schemes as more than just illicit operations being run in an ad hoc fashion. Rather, attention should be given to the intersections of legitimate and illicit business enterprises. It is also important to bear in mind that counterfeiting will likely be a supplementary criminal activity intended to generate a consistent flow of cash through relatively low-profile, yet, highly profitable activities. Finally, the highly visible presence of white-collar and occupational offending should prompt stakeholders to raise awareness of the harms caused by counterfeiting: it cannot remain a marginalized form of crime.

OVERVIEW

The illicit acts involved in product counterfeiting do not occur within a unique criminal vacuum wherein only those crimes related to, or involved with, counterfeiting schemes take place. The nature of product counterfeiting requires illicit actors to interact with many legitimate entities, meaning that in addition to violating laws protecting intellectual property rights, counterfeiters also tend to commit crimes that help to further their criminal schemes. Additionally, because counterfeiters are generalists (i.e., they do not specialize in one particular form of product counterfeiting), it may be natural to find some of them engaging in non-counterfeiting criminal schemes. Furthermore, it is not likely that product counterfeiters are more easily deterred relative to other offenders, including white-collar offenders, so we may expect to find that some counterfeiters have a history of arrests or prosecution for intellectual property rights violations.

This report details an extensive review of product counterfeiting incidents contained within the Center for Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection’s Product Counterfeiting Database (PCD). The PCD is a type of living database that contains incident-level data, gathered from open-source materials, about certain types of product counterfeiting schemes prosecuted within the United States. The majority of cases involve the counterfeiting of pharmaceuticals, electronics, food products, and automotive parts. Because database information is gathered from openly available sources, its accuracy and comprehensiveness are reliant upon two factors: the extent to which information about adjudicated cases is distributed publicly; and the efficacy and reliability of data collection efforts, a point we discuss later in this report.

The earliest cases contained within the PCD include schemes that were detected in the year 2000, while the most recent cases were criminally indicted in 2015. The original database produced a series of empirical articles, including works that examined incidents occurring within Michigan[i], the identification and classification of roles involved in pharmaceutical counterfeiting schemes[ii], and a systematic analysis of occupational pharmaceutical counterfeiting schemes[iii]. Importantly, and relevant to this report, the PCD allows for an examination of the structural features of product counterfeiting schemes as a way to understand possible points for intervention[iv],[v].

The PCD contains information about specific product counterfeiting schemes, the individual offenders involved in each scheme, and in many instances information about organizations that were criminally indicted as part of a scheme. In some instances, we have also been able to compile valuable information about the individuals victimized through these schemes, as well as the victim brand owners. The most recent additions to the database were made over the past 18 months as a result of the efforts of several A-CAPP students and staff, having received support from the National Institute of Justice[vi]. The results of this data collection effort in combination with the original information contained in the product counterfeiting database comprise the information described in this report, which has been re-analyzed specifically for this report.

METHODOLOGY

To identify counterfeiting incidents and related data A-CAPP researchers searched the websites of U.S. and international government agencies (e.g., FBI, US Customs and Border Protection, US Food and Drug Administration, Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Trade Representative, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Interpol), relevant non-governmental agencies and industry associations (e.g., World Trade Organization, World Health Organization, World Customs Organization, International Trademark Association, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy, Coalition Against Counterfeiting and Piracy, Business Software Alliance, Counterfeiting Intelligence Bureau, Pharmaceutical Security Institute, World Intellectual Property Review, World Trademark Review, Securing Industry), as well as general news websites (e.g., LexisNexis, Proquest, Google, Yahoo, Bing, NewsLibrary). Researchers searched these websites for “reports, case studies, press releases, speeches, and any other documents related to product counterfeiting”i. Finally, using the data gathered from identified cases researchers conducted keyword-specific searches of certain online sources to identify court cases and other official documents that could yield useful information about a case.

Using the information obtained through the several incident searches, the A-CAPP researchers developed “two original web-based meta-search engines to capture as much open-source information as possible for the incidents”i. Once incident data were identified A-CAPP researchers coded the data and entered it into the database. This report evaluates both the raw data, as obtained directly from the source materials, as well as emergent patterns that researchers identified from analyses of the raw data. These patterns help to identify underlying themes that exist within the data and allow us to draw general conclusions about counterfeiting incidents that may not be apparent while examining individual cases.

We primarily analyzed content found in the offender database relevant to each scheme to develop a series of descriptive codes used to identify important themes and information. However, this analysis was supplemented by an analysis of scheme data as well. Descriptive codes were used to label data segments in order to inventory qualitative data[vii] as part of an iterative coding process where descriptive codes were later refined into specific codes and emergent themes[viii],[ix]. To ensure that exhaustive search and coding processes were completed, the original searches conducted by research assistants were reviewed by a faculty researcher; this review was then subsequently checked for accuracy by other A-CAPP researchers. Finally, an A-CAPP researcher reviewed all incident files and conducted new searches to fill in any missing data from essential fields.

Individual offenders were the primary unit of analysis for our investigation, while the schemes served as a secondary unit of analyses. We focus on the individual offenders because it is individuals, not schemes, who are charged with crimes. Centering our analyses on the individual offenders allows us to gain a clearer picture of individual offending, while at the same time allowing for a multi-level examination of scheme-related offending that may span multiple individuals. This is because schemes are characterized by the criminal activities undertaken by specific offenders who may have unique criminal objectives, operate in separate locations over different time periods, and impact distinct victims.

Schemes included in our database involved illegal activities committed, in whole or in part, within the jurisdiction of the U.S. related to the counterfeiting of physical goods or packaging. These schemes were confirmed through official or verified channels (e.g., they were not simply accusations or rumors), and each led to an official government response in the form of a criminal indictment that was issued between the years 2000 and 2015. We considered an offender to be any individual who was included in an indictment from a U.S. court for their participation in activities related to, or in furtherance of, a counterfeiting scheme.

When conflicting information was found in search materials greater weight was granted to more “trusted” sources. We followed Sageman’s (2004) process of evaluating information based upon a descending order or reliability[x]. For example, appellate court proceedings would be a highly trusted source followed by court proceedings subject to cross examination (e.g., trial transcripts), court proceedings or documents not subject to cross examination (e.g., indictments), corroborated information from people with direct access to information provided (e.g., law enforcement and key informants), uncorroborated statements from people with that access, media reports, industry and watch-group reports, and finally personal views (as expressed in blogs, websites, editorials or Op-Ed, etc.). We encountered very few instances of conflicting information, which were easily resolved. In the vast majority of these instances, conflicts were due to timing differences in the information obtained – earlier sources tended to contain less accurate information relative to later sources that typically provided richer, more specific case information.

CRIMINAL ACTS THAT OVERLAP WITH COUNTERFEITING OFFENSES

We did not expect to find that the individuals involved in counterfeiting schemes would be specialists, choosing to engage solely in product counterfeiting and eschewing all other types of crime. This is true from both a technical and a practical perspective. Technically, it would be highly difficult to perpetrate a counterfeiting scheme without engaging in some other form of crime that was needed to see the scheme through to completion. Additionally, where the evidence allows, prosecutors will likely bring a wide range of charges against an individual as a way to increase their likelihood of securing a conviction in the case.

Accordingly, our data[xi] suggest that just over one-in-five individuals are charged with multiple counterfeiting-related crimes as part of their participation in a counterfeiting scheme. By far the most frequently occurring combination of charges were conspiracy and trafficking in counterfeit goods, which were the combination of charges handed down to 65% of individuals charged with multiple counterfeiting related crimes. A distant second on the list of overlapping counterfeiting related crimes were charges of trafficking and distribution/sale of counterfeits (13%), followed by smuggling and trafficking (9.5%).

Finding that so many people were charged with conspiracy makes sense as an average of 2.7 people were indicted for each counterfeiting scheme we examined. However, in just over 54% of schemes only one person was indicted. This suggests that while many schemes may appear, given criminal indictments, to be relatively small as 91.8% of schemes involve five or fewer people, some are much larger as 5.1% of schemes involved 6 to 10 people; the largest operations (11 or more people) made up only 3.1% of schemes. The number of conspiracy charges also makes sense given that 1 in 8 individuals was in some way involved in the distribution of counterfeit goods, many of whom were members of a group engaged in a counterfeiting scheme. Accordingly, it may seem sensible to focus intervention and detection methods in distribution channels, as a way to identify counterfeiting behavior, but also as a way to identify highly visible roles within a counterfeiting scheme.

Practically, we should consider the individuals involved in product counterfeiting schemes to be generalists who may be likely to engage in a range of criminal schemes because these acts have an indiscriminate profit motive. While there will be some specialization in offending, this is most likely to be found in individuals who commit counterfeiting offenses as a form of occupational offending. Occupational offenders use their positions as a veil of legitimacy over their deviant acts and have the potential to create great harm by virtue of their ability to control guardianship and oversight strategies at their places of business. The individuals who can most manipulate legitimate occupational settings to facilitate counterfeiting schemes are business owners, or individuals who by virtue of their positions have wide discretion, responsibility and respectability.

We found that 13.2% of the individuals involved in counterfeiting schemes were the owner or co-owner of a legitimate business, and in most cases, we found clear evidence that the individuals used their business to facilitate some part of the scheme. More troubling is the finding that 11.3% of the individuals we identified were licensed healthcare providers (i.e., a doctor, pharmacist, veterinarian, nurse, paramedic). These individuals’ schemes were tied to their professions, which allowed them access to vulnerable targets (i.e., patients) within settings where they enjoyed large amounts of trust and often unquestioned decision-making. Not surprisingly, we found 26 cases (4.7% of individuals) involving a concurrent charge of adulteration, and 15 cases (2.7% of individuals) with a concurrent charge of healthcare fraud, which are both occupationally-related healthcare offenses. For occupational counterfeiters their crimes coincide with legitimate business activities, and opportunities to proactively identify clues that occupational counterfeiting may be occurring are often tied to the individual’s workplace activities (for a detailed discussion of this, see the article written by Kennedy, Haberman and Wilson on occupational pharmaceutical counterfeitingiii).

The mercenary, or financially focused, nature of product counterfeiting suggests that offenders do not commit these crimes because they see value in counterfeiting per se; rather, individuals participate in these schemes because they are lucrative. Supporting this, we found that the median illicit revenue generated by counterfeiting schemes was $1,400,000; the least profitable scheme netted just $6,000, while the two most profitable schemes each generated about $80,000,000 in illicit gains. As these numbers highlight, counterfeiting schemes create powerful financial incentives for individuals and organizations seeking to enrich themselves or support some licit or illicit activity.

Counterfeiting also attracts individuals with criminal histories, some of them with substantial histories, as just over 5% of individuals involved in counterfeiting schemes had prior convictions for some other crime (some of which were counterfeiting crimes) or were involved in other serious deviant acts before being charged with the counterfeiting-related offenses in the schemes we investigated. Most individuals with prior criminal histories, 30%, were charged with a crime related in some way to illicit drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, MDMA, etc.) through either trafficking, sale, possession, or distribution. Surprisingly, another 27.5% of individuals with prior criminal histories had charges in the areas of fraud, white-collar crime, and occupational offending. 12.5% of individuals had a prior history of intellectual property crimes or counterfeiting, 10% had a prior history of property crimes, and 7.5% had committed a crime against a person prior to their involvement in a counterfeiting scheme.

As mentioned earlier, several occupational counterfeiters engaged in concurrent crimes, offenses that overlapped with their counterfeiting activities. Non-occupational counterfeiters also engaged in a host of additional crimes that were concurrent to their counterfeiting offenses, and for which they were charged. Across all individuals the most commonly charged concurrent crimes were white-collar and occupational offenses, which accounted for 34.4% of all concurrent crimes. The most commonly charged white-collar crime was money laundering, which might be expected given the large number of businesses involved in schemes, as well as the large number of illicit drug crimes (e.g., cocaine, marijuana, MDMA) that were charged. Additional white-collar and occupational offenses charged concurrently with counterfeiting offenses included tax evasion, a range of frauds (mortgage, immigration, insurance and healthcare which was a relatively frequent occurrence), forgery, creating false identities, environmental violations, and the adulteration of prescription drugs.

Intellectual property and counterfeiting offenses were the next most common concurrent charges, representing 28.7% of all concurrent charges. This category included many different acts, such as the sale of counterfeit goods other than those charged in the primary counterfeiting case, distribution of pirated software, copyright infringement, and DVD piracy. Drug offenses (16.7% of concurrent charges) primarily consisted of illegal drug trafficking, with a few individuals being charged with possession or the sale of illicit drugs. The property crimes that were charged concurrent to counterfeiting offenses consisted almost exclusively of trafficking in stolen goods, with fewer than ten individuals charged with various theft offenses.

Finally, there were a number of quite serious crimes against persons charged concurrently with counterfeiting crimes. These included assault with a deadly weapon, attempted homicide, and the administration of adulterated drugs to unsuspecting patients. The category of ‘Other Offenses’ served as a catchall for a litany of illegal behaviors, including crimes of smuggling, selling or purchasing an illegal firearm, prostitution, possession of an illegal assault weapon, selling fraudulent passports, and as mentioned above the identified links to terrorist activities. While these individuals represent less than 1% of all the individuals in our database, their activities have the potential to have far reaching consequences. In addition to counterfeiting, these individuals were concurrently charged with providing material support (weapons) for terrorism, and the financing of terrorism and terrorist organizations.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its outward appearance, product counterfeiting is far from being a stand-alone crime. By its very nature, it overlaps with many other criminal activities as counterfeiters must leverage legitimate organizations in the processes of manufacturing, distribution and the sale of counterfeit goods. Furthermore, the large financial returns to be gained from counterfeiting likely attract a host of illicit actors who are intent on taking advantage of opportunities to make a lot of money, while exposing themselves to relatively little risk. Yet, the convergent nature of the criminal schemes described in this report suggest much about ways to mitigate counterfeiting opportunities.

Our investigation highlights the importance of thinking about counterfeiting schemes as more than just illicit operations being run in an ad hoc fashion. Rather, the fact that so many schemes were related to legitimate organizations suggests that attention should be given to the intersections of legitimate and illicit business enterprises. Legitimate businesses offer cover for illicit economic activities because they provide a legitimate rationalization for trade and commerce, a rationalization that likely inhibits deep inquiry into the status of the goods moving through the business. Businesses are supposed to engage in the very activities involved in counterfeiting (e.g., manufacturing or procuring products, distribution and sale of goods), so businesses may be less likely to be scrutinized about their behavior than would a loose affiliation of individuals or a single person ordering large quantities of product from China. Additionally, businesses shield individuals from scrutiny since business people are not commonly thought to be engaged in counterfeiting.

Future attempts to understand the structure for counterfeiting schemes must focus on the opportunities that present themselves through legitimate business enterprises. This focus must move beyond the attention given to suppliers running unauthorized third shifts, or distributors who divert legitimate goods into grey- or black-market channels. Rather, it must focus on identifying patterns in deviant and criminal organizational behavior that may signal counterfeiting or other crimes are taking place. In particular, it is important to look for signs of counterfeiting in cases where legitimate businesses or business owners operate within an industry where products are sold or distributed, and they are attempting to hide excess income through money laundering or tax evasion schemes.

It is also important to give greater consideration to the fact that counterfeiting will likely be a supplementary criminal activity for individuals and groups looking to generate a consistent flow of cash through relatively low-profile, yet, highly profitable activities. In particular, organized crime groups, drug gangs (whether they be a highly formalized and recognized gang, or a loose affiliation of individual actors), and terrorist organizations and their sympathizers. These groups will use counterfeiting, not as a way to advance a particular agenda, but rather to generate the cash needed to support their primary criminal activities. Accordingly, mitigating opportunities for product counterfeiting is one way of cutting off the flow of funds these groups need to operate their illicit organizations.

While the connections between counterfeiting and organized criminal entities may appear tenuous at the present, it is likely the case that the severity of these groups primary activities overshadows their “less serious” forms of offending. Working with law enforcement agencies to raise levels of knowledge, awareness, and education about the value of searching for signs of counterfeiting activities among these groups can pay substantial dividends from a relatively small investment of time.

Finally, the highly visible presence of white-collar and occupational offending highlights an important lesson for brand owners, law enforcement, solutions providers, and all other stakeholders: counterfeiting cannot remain a marginalized form of crime. White-collar crimes and white-collar offenders are in general perceived to be less harmful than are street crimes and traditional offenders[xii]. Additionally, the public generally seeks to impose less punitive sanctions on white-collar offenders, believing them to be less harmful to society and less of a threat than traditional street offenders. This perception of the seriousness of white-collar crime, and the harms this type of crime imposes on society and victims, may foreshadow social perceptions of the seriousness of product counterfeiting. The general social perception for both white-collar crime and counterfeiting may be that they happen to infrequently, or do not lead to substantial or broad enough social harms as to warrant large-scale attention. People may see this as a problem best handled by business, but not requiring copious amounts of official intervention. This perception may lie behind the behavior of the occupational offenders in our sample. In essence, they may see both counterfeiting and white-collar/occupational crimes are relatively low-risk, high reward endeavors. As such, committing a counterfeiting offense is the rational thing to do.

The last theme to emerge from the data relates to the way in which we describe the individuals involved in counterfeiting schemes. Throughout this report these individuals have been referred to as “counterfeiters”, which is also the default term used by brand owners, solutions providers, and other stakeholders. In many ways, this label makes sense as these individuals are involved in counterfeiting schemes and when caught are charged with counterfeiting offenses. However, it may be more appropriate to move towards a more nuanced lexicon. Some of our prior research on the specific roles undertaken by individuals involved in product counterfeiting schemesiii argues that it is inappropriate to use the term “counterfeiter” to describe every individual involved in a product counterfeiting scheme. Rather, this term should be reserved for those individuals who actually manufacture a counterfeit product or produce packaging or materials bearing counterfeit marks. We continue to support this argument.

Many of the individuals found in our searches committed crimes or deviant acts that facilitated the manufacture, packaging, sale, or distribution of counterfeit products, yet, they themselves did not “counterfeit” any good. This does not diminish their criminal activities, but rather helps to frame their actual behavior and points to opportunities for potential interventions. The interventions undertaken to address the illegal behavior of a manufacturer of counterfeits should be distinct from those used to address the individuals and groups that serve as logistical middlemen, receiving large amounts of counterfeit goods from foreign sources and then distributing those goods to numerous partners before they are sold to consumers. Accordingly, the language is used to describe these individuals should highlight their specific role in a scheme as a way to reinforce the need to think more specifically about ways to mitigate counterfeiting risks. Global approaches that treat all actors as conceptually similar may be efficient, but they may not lead to the most effective solutions or interventions.

[i] Heinonen, J. A. & Wilson, J. M. (2012). Product counterfeiting at the state level: An empirical examination of Michigan-related incidents. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 36(4), 273-290.

[ii] Kennedy, Jay P., Ksenia Petlakh, and Jeremy M. Wilson (2018)“A preliminary investigation of pharmaceutical counterfeiters in the United States.” Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice and Criminology, 7(1), 49-74.

[iii] Kennedy, Jay P., Cory P. Haberman and Jeremy M. Wilson (2018). Occupational pharmaceutical counterfeiting schemes: A crime scripts analysis.” Victims and Offenders, 13(2), 196-214.

[iv] Clarke, R. V., & Cornish, D. B. (1985). Modeling offenders’ decisions: A framework for research and policy. Crime & Just., 6, 147-185.

[v] Cohen, L. E. & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588-608.

[vi] National Institute of Justice Award No. 2016-R2-CX-0052. Awarded to Brandon Sullivan, Ph.D & Jeremy Wilson, Ph.D.

[vii] Saldaña, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

[viii] Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine-Athestor.

[ix] Miles, M. B. & Hubberman, A. M. (1994). An Expanded Sourcebook: Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[x] Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press (2004)

[xi] We were able to obtain reliable data on 196 product counterfeiting schemes and 551 individuals.

[xii] Michel, C. (2016). Violent street crime versus harmful white-collar crime: A comparison of perceived seriousness and punitiveness. Critical Criminology, 24(1), 127-143.